A History of Carnage: Part I

A telling of the spine-break/heart-break that is the cinematic journey of Spider-Man.

I was supposed to write something light for this month, but you know how ideas work: they grip you and keep you awake till 4 AM until you’re happy with the research you’ve done. This story is one of them. I hope it is as fun to read for you as it has been for me to research it, structure it, assign some morality to every stakeholder, and write it! Happy New Year!

It should have been impossible to make the beautiful throwback that was No Way Home, especially after the dispute between Sony and Disney that saw it almost never get made. A little digging proved that this dispute has been, for more than 40 years, bigger than just the Sony-Disney deal. And there are only pieces of this entire saga strewn across different corners of the internet - documentaries, news archives, intensive coverage, entertainment blogs, and Reddit. This is an attempt to make sense of that story, and it is most definitely, in true sense of the term, a story.

Peter Parker/Spider-Man has seen enough, and I don’t mean Doc Ock, Green Goblin, the death of Uncle Ben, symbiotes, and failed relationships. The friendly neighborhood hero’s actual obstacles lies in mail chains, Hollywood studios, ambitious directors, ambitious big-ego producers, and slashed budgets. And at the end of it all, three actors who just wanted to be who they were.

This is a three-part story, and this trilogy division is a complete coincidence. That being said, here’s the division, and each part has its own title, named after songs whose choices might be pretty evident:

Part I: When It Started, by The Strokes (~1980-1996)

Part II: Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head, by BJ Thomas (1996-2012)

Part III: They Say It’s Wonderful, by Frank Sinatra (2012-2021)

It is also worth mentioning that there are no spoilers for No Way Home, or anything from the MCU' Spider-Man! Happy reading!

When It Started, by The Strokes

Cast: Menahem Golan, Yoram Globus, Giancarlo Parretti, Frans Afman, Stan Lee, Ted Newsom, John Brancato, Joe Zito, Don Michael Paul, Ethan Whiley, Neil Ruttenberg, James Cameron

Other parties: MGM Studios, Credit Lyonnais, Marvel Comics, Columbia Pictures/Tri-Star Pictures, Carolco Pictures, Viacom

The story of Spider-Man, or at least the movie rights to him, starts all the way back with a B-movie studio, led by one man who tried to make a living by creating movies about ninjas and low-budget rip-offs of storied franchises.

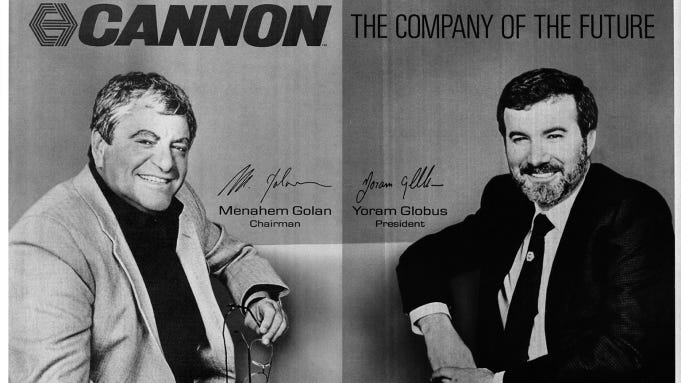

Menahem Golan was the son of two Jewish emigrants from 1939-era Poland (that is, before Nazi Germany took over). After a stint as a pilot in the Israeli Air Force, Golan put his education in filmmaking and drama to use in working as an assistant to director Roger Corman. Before anyone knew it, he was directing his own films along with his cousin Yoram Globus. The two of them infused new blood into Israeli cinema in the 60s and 70s.

His passion for films was infectious, and for better or for worse, he would go to any lengths to have his scripts made. BBC covered his operation style as part of their Omnibus series, and he seemed to unilaterally decide the terms his contracts. He was a tough cookie to work with, a blunt negotiator, a super-savvy salesman, and ambitious as hell. His tendency to discipline his already low-budget movies was incredible, and, one might argue, impossible. So much so that he lived extremely humbly. In the BBC documentary on Golan, Israeli production executive Itzik Kol recalls him saying this:

“I don’t have a car, I don’t have a fridge, I don’t even have a house. The only things I have are my wife and my three daughters. If you can put a mortgage on my wife and daughters, I’m okay with it!”

And he was explosive. On set, he once wielded a sub-machine Uzi at a stunt pilot, ordering him to return to his cockpit. Globus, on the other hand, was milder, younger, more risk-taking. The two of them together, however, were yin and yang.

Their real shot at running shows came in 1979, when he bought a distressed British studio called Cannon Films. Under Golan, Cannon Films had an interesting business model. Every year, they would make tons of movies with cheap production, ideally to make a good profit on them. It’s safe to say that script-writing was not an important consideration for them, just a lot of sci-fi flash, or kickboxing, or shooting, or Chuck Norris/Sylvester Stallone/Jean-Claude Van Damme. They were one of the first to exploit the direct-to-video market, because VHS tapes had become a choice medium of consumption. More importantly, the TV rights to these movies would be sold overseas, much before the actual movie was fully made, thereby getting Golan and Globus some cash, which would then be used to make “true cinema” projects with the likes of Robert Altman, Jean Luc-Godard, and John Cassavetes. Golan and Globus were among the first to realize the international potential of American movies. They’d release 10-12 films in a single year, and that number went up to 43 in 1986. A substantial fraction of these flicks succeeding should ideally put them well above the red line.

But when you make more bank as a small studio, of course you want to try handling an A-list project. Which is why Golan thought it would be fun to try and make a superhero movie. Cannon bought the rights to our friendly neighborhood web shooter for a meagre $225K in 1985, with an expiry date of April 1990.

In that same year, Golan also thought that it would be nice to give the Cannon spa treatment to another superhero who was on the wane after a bad third instalment (and two legendary features before it). But still, indubitably, the greatest American superhero at the time.

Metropolis might be a great city, but as intellectual property, it was rotting. Superman III sucked. It made a cool $80M on a $36M budget, but after the sort of critical response it received, nobody was willing to risk their reputation again. Some, like director of I and II Richard Donner, were blacklisted to even try. A-list studios didn’t didn’t want any part in superhero stuff.

But Golan saw an opportunity and wrote a $5M cheque for the rights to Superman. It sounds pretty cheap when you think about it, right? Superman was the first major superhero franchise. Even after accounting for inflation and franchise reputation, it’d be insane to get a deal like that, with what we know now about how theater runs hardly make money. Even crazier when Golan paid $225K for Spidey, while that same deal has raked in tens of millions of worth. But the businessmen of movies back then didn’t attach the money worth to the rights that would originate from merchandise.

So, we now have Cannon Films who have a new director named Sidney J Furie, much of the same cast - including leading man Christopher Reeve (who was also promised funding for a vanity adult project), and a ~$35M budget. To make Superman IV: The Quest For Peace. What could possibly go wrong?

The budget was slashed to a paltry $17M within a month of production. Reeve mentioned that Cannon had around 30 projects running simultaneously at the time, and Superman IV received no special consideration from Golan. There was one scene meant to be shot at the UN headquarters in New York, but instead, the crew was forced to make do with Milton Keynes, in England. What’s even funnier is that before production on Superman IV even began, Golan wasn’t budging with Reeve for his vanity project’s funding, to which Reeve, the unknowing foreteller of bad juju, said:

“If you don’t have another million-and-a-half to do this movie in New York, how do I know you have $30m to do Superman?”

Superman IV made ~40% on its $17M budget in the theater in the opening weekend, and grossed just $36M worldwide by the end of its run: only twice the budget. A few bad acquisitions, an SEC investigation, and the failure of the business model itself saw them on the verge of filing for bankruptcy. The only thing that could save them was a buyout.

Enter an Italian “businessman” named Giancarlo Paretti.

Paretti was an unabashed personality. He began his career as a waiter, but in a few years’ time, racked up counts for violating securities laws, bankrupting a soccer team and a hotel, fraud, issuing bad checks, and much later, being the face of a lending crisis in Hollywood, along with a bank named Credit Lyonnais. He was also a man of the highest order of indulgence, misusing company payroll for drugs, sex, booze, and the like.

Through one of his holdings - Pathe Communications - Paretti offers to buy Cannon. Golan and Globus meet him at the Carlton, accompanied by a banker from the Credit Lyonnais named Frans Afman, who led entertainment lending for the bank. This conversation below from that meeting, courtesy CNN Money, is a good representation of the kind of peculiarity Paretti is. Note that Paretti shouts all of this:

“You, Afman!”

“Yes.”

“How much you make at that bank?”

(hesitation from Afman)

“I double it!”

(Afman looks wide-eyed at Globus)

“Not enough? I triple it! I triple your salary--if you come into my company.”

“Wait a moment, Mr. Parretti. I'm not here to discuss my salary with the bank. I'm here to discuss your possible investment in Cannon.”

After continued persuasion from Paretti, Afman says, “I'd have to give up my job at the Credit Lyonnais”.

"That wouldn't be necessary--on the contrary." (it was a bribe)

This was the beginning of a toxic partnership between Parretti and Credit Lyonnais that warrants its own separate piece. But in short: Lyonnais lent a lot of money to Parretti that they never saw again, across various dealings, most notably to buy the great MGM Studios in 1990. This fact will be important later in the story.

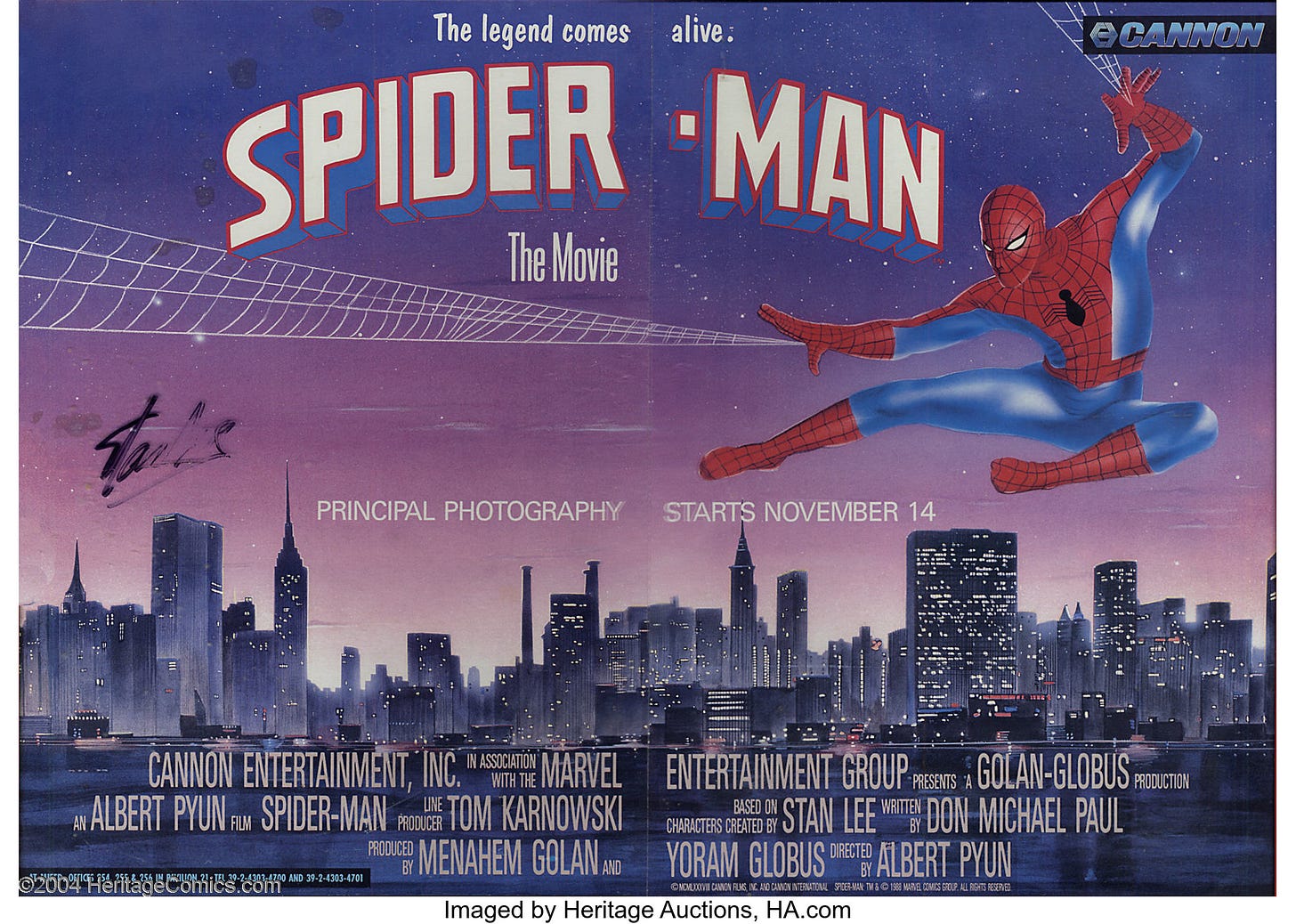

Recharged with new funds, in the midst of slashed budgets and avant-garde failures, Cannon was trying to make a Spider-Man movie, to be released by Christmas 1986. Advertisements were taken out well before the movie. A newly-minted comics executive named Stan Lee wanted to make a grand splash in Hollywood like DC did. The only attempt so far in this regard was a small TV movie in 1978…about Spider-Man. But Lee wanted to Hulk-Smash the theaters now, and got writers Ted Newsom and John Brancato to write a draft.

Newsom and Brancato had made a living writing B-movie scripts, but they seemed primed to write a script, in which they included a well-built Peter, a hip (yes, like Marisa Tomei) Aunt May to be played by a Katharine Hepburn-type, and a physically-altered Doc Ock who wanted to mess with gravity. After rewrites from director Joe Zito and another co-writer Barney Cohen, there was some semblance of completion.

The only problem? Golan didn’t understand Spider-Man at all.

As per conversations with Empire writer Edward Gross, each of the writers and Zito complained about Golan's disconnect from the character. From thinking Spidey is just a younger Superman in sensibilities, to NOT getting the clumsy-yet-weighty duality that Peter Parker embodies — if made, this was always doomed to be a disaster. The first ever draft that Golan commissioned (not involving any of the people above) had Spidey be a suicidal human tarantula. And of course Stan Lee wasn’t happy with it. But every rewrite since the Newsom-Brancato edition made it worse.

The real bummer, however, was the budget. Initially assigned $20M, the movie was an attraction for other celebrities who grew up reading the comics. Only to have Golan cut it to a meager $10M, and the way the script was written, visual effects alone needed $5M. Spidey went from swinging in Queens to development hell.

You might probably be wondering; why did Marvel sell to a B-movie that lived cheque to cheque? The short answer is that bigger studios STILL hadn’t warmed up to comics. Marvel’s film agent, Don Kopaloff, answers this in a book titled Stan Lee and The Rise and Fall of the American Comic Book:

“I would never have gone to [Cannon] as a first choice. I went to them after I couldn't get Captain America or Spider-Man sold.”

In 1988, after the Pathe acquisition, the stubborn, ever-persistent Golan wanted to try making his baby again. This time, he got a small-time writer named Don Michael Paul to tackle the script. The man wrote a gruesome and violent tale, involving a new, genetically messed-up, vampire-like villain named Night Ghoul. And the budget was still a bit much for Cannon. When this failed, Golan hired Ethan Whiley to write a script that would allow Cannon to make the movie in under $5M.

Whiley had experience writing low-budget/highly profitable horror movies, and he also came with some VFX experience, having worked on Return of the Jedi. He was explicitly asked to not use any villains like Doc Ock, and in general, there was (legal) ambiguity around what characters he could include. So, he ended up making a paraplegic doctor who was really good at his job, but had a burning desire to walk again. He injects himself with a serum to cure his lack of ambulation, and that converts him into a scorpion man.

Which, if you think about it, is only a lizard’s tail away from being similar to another Spider-Man villain :)

By 1989, though, Golan didn’t align with Parretti, who eventually made Golan a scapegoat for Cannon’s shoddy run. Golan was fired. But in return, Parretti gave him a severance package: the reins to one of Parretti’s own holdings - 21st Century Film Corporation, the rights to Spider-Man, and the rights to Captain America. Globus was made studio head, and this is where the story of Cannon ends. Cannon shut shop in 1993, and was sold to MGM - the same holding that owned 21st Century.

Which, if you remember, was owned by our favorite Italian crook for a little while :) we’ll return to MGM in a bit.

Golan continued to persevere for his vision of Spider-Man. As part of 21st Century, he renewed the deal with Marvel in 1989, but this time without any deadline for the expiry of ownership. And if he didn’t make a movie by end of 1991, every attempt after that would have to go through Marvel’s approval. At Cannes that year, he announced a Spider-Man movie, crediting Zito, Newsom, Brancato, and himself. Cannon sold TV rights to the un-made movie to Viacom, and home video rights to the Sony-owned Columbia Pictures — the distributor that will eventually play an important role in bringing Spider-Man to the world in the 2000s. Golan got a new-new writer, Neil Ruttenberg, to handle the script. Ruttenberg mentioned to Empire that Golan knew a lot about film, but had terrible staff that always stifled his writing process, and a reputation that made Golan the butt of the industry. More importantly, he believed that Golan’s thought process was not the most sustainable. One that might also partly explain what went wrong with Superman IV:

“I would say my script didn’t work for the reason that the chemistry with the executives was all wrong. Menahem would tend to grab on to an idea, love it, then divorce himself from it and let his staff deal with it and move on to the next big deal. He was running towards the end of his career, but he was still trying to play the kingmaker.”

As expected, 21st Century clearly went down the same path as Cannon. The budget for the movie continued to lower, until some Carolco Pictures agreed to step in with co-financing. Carolco made Rambo, Total Recall, and one of the greatest sci-fi films in Terminator 2: Judgement Day. They serenaded Golan on the company yacht at Cannes, and signed movie rights to the character for $5M, with a kicker from Golan’s end: that he be given his due in the final product. And because of this lovely coincidence came a bold, ambitious man who would be the mere tip of the inconspicuous iceberg in front of an already sinking ship, named James Cameron.

In an interview with The Wrap, Marvel writer Chris Claremont describes a meeting in 1990, when he and Stan Lee visited Cameron in the office of his own production company, Lightstorm Entertainment. This was to pitch an X-Men movie. The pitch was insane: an X-Men movie, produced by James Cameron, and directed by Kathryn Bigelow (of The Hurt Locker). Cameron and Bigelow were a power couple at the time, so the chemistry would have been off the charts. But Lee goes off on a different tangent, looks into Cameron’s eyes, and says:

“I hear you like Spider-Man.”

And that was it. A tank full of lava, much like in T2, lit up Cameron’s ass, and he began fleshing out his story idea.

Cameron was hot, in more ways than one. Terminator, Aliens, The Abyss, T2 - the man wasn’t just the mint, he was also the money the machine printed, as he would prove twice over later: once in 1998 with Titanic, and once in 2009 with the Blue Man Group. And naturally, his own venture, Lightstorm was co-producer on all of his own movies. Carolco paid him $3M upfront to handle Spider-Man.

But he was also hot: he called the British crew for Aliens lazy and rude because they took tea breaks, made life on the set of The Abyss so difficult that lead actor Ed Harris punched him, and was the sort of perfectionist to nearly kill himself underwater (while making the same movie). He demanded complete creative control in his movies.

Carolco, however, made a teeny-tiny mistake in the $3M contract they gave Cameron. The contract for T2: Judgement Day stated that Cameron would have the right to approve/refuse all credits. For Spider-Man, they basically took the same contract, replaced T2 with Spider-Man, and had him sign it. And as you’d expect from a man of his disposition - James Cameron was uncompromising on keeping Golan’s name OFF the movie. It really takes one iceberg.

Golan was mad, and Carolco pressurized him to cave in. But if we know anything about Golan, it’s that he isn’t the kind to concede. He sued in 1993. And that led to some things being said in court. The LA Times reported that one witness Carolco produced basically shat on Golan. Crediting Golan would have only one meaning: “to show the remainder of the entertainment industry that Golan has the bargaining power to obtain a credit for rendering no service”. No one in Hollywood would ever believe that Golan had anything substantial to contribute in production. He was washed.

Of course, a lawsuit meant that any efforts to produce the movie had to be held for the time being. But along with legal troubles, Carolco had a string of financial issues because of a few box office bombs, over-payments to marquee stars like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, and the loss of multiple partnerships. This had earlier forced them to sell some assets, which also included the movie rights to Spider-Man, to some big studio, for 15% ownership.

To MGM. I told you they’d be back :)

That’s right. Mr Flashy himself, Giancarlo Parretti has returned to this tale, but not in a way you’d expect. He lost ownership of MGM amidst some very shady dealings, like giving his own daughter an executive role, and making no new films in his time. The SEC and FBI launched investigations into his leadership of MGM. In 1992, Credit Lyonnais (welcome back) became the de facto owner of the studio.

But along with MGM come a few more bodies who realized that they could stake their own claims. Remember how Viacom and Columbia (through subsidiary Tri-Star) had TV and home video rights to Spidey, respectively? Now Carolco wanted to nullify that deal between Cannon and the two studios, and launched a lawsuit against them.

Only to get counter-sued by them! And the Columbia-Viacom tag-team didn’t stop there. Remember 21st Century’s deal with Marvel? Not having any explicit deadline implicitly meant 21st Century could own Spider-Man….forever. This was unheard of in the industry at the time, and probably still is in the present time. In 1994, the duo also sued 21st Century and Marvel at this atrocity, in an attempt to gain every right to the character. That’s 3 lawsuits in the span of a year. And it gets worse.

The lion in the room, and the legal father of 21st Century, MGM didn’t like this. MGM’s position was that Marvel deliberately didn’t give them a deadline, because if Marvel had an option to take them back, bankers wouldn’t lend to 21st Century. MGM sued EVERYONE: 21st Century, Viacom, Tri-Star/Columbia, and Marvel, and along with that - Golan, Globus, and Parretti! Full endgame.

For all purposes, here’s a diagram for you to make sense of this hullabaloo:

It didn’t matter, though, because by 1996, 21st Century, Carolco, and most importantly, Marvel, all filed for bankruptcy. 21st Century had to sell its entire library to MGM. Marvel took a hit because they kept raising prices, in the hope that comics collectors would eat it up. At some point, those same collectors started having less money due to volatile markets, and stopped buying mint editions. And Marvel didn’t have a full-fledged entertainment division, yet. In all that blurry, incomprehensible disorder, Marvel actually had its rights returned by the judge.

This is also where the relationship between Menahem Golan and Spider-Man comes to an end. Golan continued to make low-budget films after 21st Century, none of which had to do with any superheroes. He passed away in 2014, and he had his share of revolutionizing cinema. While he made a lot of cheap exploitation films, he brought his flair to a lot of bold features, too. It is remarkable that as an outsider to Hollywood, he flipped the movie business on its head, for good and bad, but all in honest faith. This small tribute on Roger Ebert’s website (who sadly passed away the very same year) puts Golan in scintillating perspective:

“Since its inception, the film industry has attracted all sorts of colorful types—hucksters willing to churn out the sleaziest junk imaginable in order to make a quick buck, idealists with a desire to make great art regardless of the cost, glory grabbers who crave the spotlight and all the adulation that comes with it and gamblers possessing the will to risk it all and the nerve to do it all over again if that big bet fails to pay off. However, few have embodied all of those traits as boldly as Menachem (sometimes Menahem) Golan, who died earlier today at the age of 85. Throughout a long career that saw him working as a producer, director and eventually the head of his own studio, he brought together art, commerce and sheer chutzpah in such a way that if one even dared to make up such a character in a fictional work, such a creation would be dunned as being simply too good to be true.”

What is, however, the saddest part of this story is that James Cameron had a working idea for the movie. And that’s what I’ll end this part with. If not for the legal battle, we could have seen a gritty, visually spectacular version of Spidey early on. I have read the original story that Cameron outlined, and it is a little too dark for a Spidey movie. Nonetheless, it seemed wonderfully coming-of-age, and largely set the tone for possibilities in the future. It had cool villains in Electro and Sandman, Peter struggling through changes in his body and dealing with his dual life, and pining for Mary Jane Watson. No doubt it would have received a hard R-rating (Peter and MJ have sex, and Peter does some trash-talking). No doubt it would have insane visual effects, courtesy Cameron.

But the most important element, and a small neck bite that would evolve into a ripped body and 20/20 vision in Part II of this story?

Peter Parker shot webs organically instead of through any wrist devices :)

Cant wait for part II

Banger