A History of Carnage: Part II

A telling of the spine-break/heart-break that is the cinematic journey of Spider-Man.

Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head, by BJ Thomas

Cast: Ron Perelman, Carl Icahn, Avi Arad, Ike Perlmutter, Amy Pascal, Sam Raimi, David Koepp, Alvin Sargent, James Vanderbilt, Amir Malin, Kevin Feige, David Maisel, Andrew Garfield, Emma Stone, Marc Webb

Other parties: Marvel Entertainment, ToyBiz, Sony/Columbia Pictures, MGM

So, Marvel is dead now. The year is 1996, and the bankruptcy declaration was not without its drama. Erstwhile owner Ron Perelman was trying to save the company’s face, and his last-ditch effort involved a restructuring plan. His initial plan was to create a stronger, separate entity called Marvel Studios. That involved buying more shares of one of Marvel’s subsidiaries, named ToyBiz, and then merging the two.

Shareholders resisted it, on the notion that this was a deathly move for a stock that was already falling. The shares of Marvel were basically collateral for loans raised through junk bonds, which, as the name states, have terrible repayment probabilities. One of those shareholders was infamous corporate raider Carl Icahn, who offered his own bankruptcy restructuring plan, promising to pay off all creditors.

At the heart of this were two people who would change the course of the superhero movie business altogether in the next 2 decades. They were executives of ToyBiz, Avi Arad and Ike Perlmutter. They knew that the future of Marvel was toys. Merchandise. They wanted a new future for Marvel, but it was stuck in a long-drawn court battle between Perelman and Icahn, which so involved throwing off Arad from Marvel because he can't have positions in both entities. In return, Arad and Perlmutter had ousted both of them, along with other executives who were Perelman loyalists.

Known as an expert cost-cutter, Ike Perlmutter has always maintained a mysterious image. He started his career selling cosmetics on the streets of New York, and, of course, toys, that eventually led him here. But since he became a hotshot, he has hardly been photographed outside, and morbidly avoids interviews. Whatever you read about him, his miserliness stands out. There are many instances of his fair share of controversies: opposing Black Panther and Captain Marvel, being a Trump supporter, and being a bit of a racist. Remember when Don Cheadle replaced Terence Winter to be James Rhodes in Iron Man? Apparently, Cheadle signed for cheaper, and Perlmutter said that no one would notice because “black people look the same”.

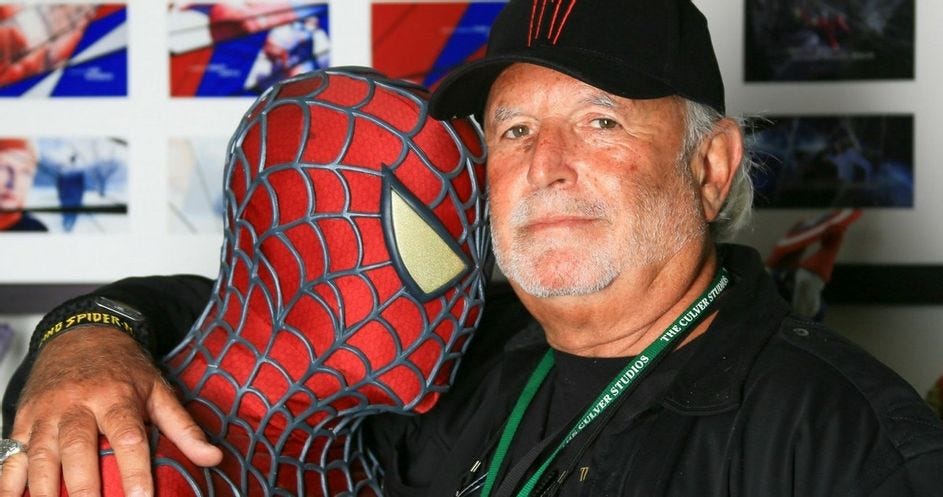

Avi Arad flourished as the CEO of ToyBiz. He sold $30M worth of X-Men toys in the 1990s, and also helped launch its beloved animated series with Fox. He seemed to truly LOVE the characters, so much so that he was ready to make movies about them. And in that vein, the X-Men movie saw the light of day in 2000.

What’s funny is that the X-Men movie could have been made a decade before its release. Remember Stan Lee and Chris Claremont’s meeting with James Cameron? It so happens that Kathryn Bigelow did write a first draft script for the X-Men movie. That got ignored for quite a while because all eyes were devoted to Spider-Man, until Arad’s X-Men TV show show saw success in 1992-93.

This feature of Arad by Deadline contained a small paragraph describing Arad’s animation about all things Marvel, through the clothes he wore in a meeting with the writer of the piece:

“I remember Arad was proudly wearing a shiny, silver Punisher skull ring, a Spider-Man ball cap and a Wolverine shirt under his jacket that morning, but my strongest recollection was his gusto for all things Marvel.”

But Arad will face his character reckoning in this saga as we go along. For now, Marvel is trying to get back on its feet, and they do so by licensing usage of their characters for various purposes. One outfit named New Line Cinema decided to strike a licensing deal with Arad for some little-known vampire-killer from Marvel’s roster of characters - a wild change from attempts to realize Spideys and Captain Americas.

However, this vampire-killer named Blade made $131M against a $45M budget: a winner by all standards. This opened up doors for Marvel, and offers came from all sorts of companies. Including one called Sony.

Sony, as you know now, was not a newbie to the legal mess of Spider-Man. Sony owned Columbia Pictures, which in turn owned Tri-Star Pictures. Before they could free Spider-Man from the clutches of the Constitution’s mercy, they needed to take care of their own Lady Liberty in Columbia. Thankfully, the judge dismissed many of the claims in the aforementioned world-ending lawsuit that MGM had initiated. Marvel was free to give Spider-Man a new home.

Arad, in particular, was unwavering in his belief that Spider-Man was going to be a mammoth business-wise. In a meeting to discuss bankruptcy plans in 1996, Arad was as blunt as one could be:

“I feel certain that Spider-Man alone is worth a billion dollars. But now at this crazy hour, at this juncture, you’re going to take 380 million—whatever it is from Carl Icahn—for the whole thing? One thing is worth a billion!”

And for ~$7M (and a ~$10M advance), Marvel gave Spidey new shelter. Sony got the rights to two Spider-Man movies, and a TV show. Marvel would only be entitled to 5% of the money the potential movie(s) would make, and merchandise profits would be divided equally among the two entities. For future purposes, let this be called Deal 1.

Meanwhile, MGM had seen enough. Giancarlo Parretti was being sued by the American government, but he had fled the country. Credit Lyonnais got control of the firm, but it couldn’t possibly fathom its own losses because of that stressed ownership. They were also facing losses in real estate and finance, and were being counter-sued by Parretti, of all people. They ended up selling to the previous owner, Kirk Kerkorian, in 1996. MGM pursued to restore their glory by buying multiple libraries, which included the entire James Bond franchise. Except the rights to one property were still owned by Sony, who still needed a script.

The solution? MGM trades their own work on their Spider-Man movie (read: every version of the doomed script) in exchange for the book, that would eventually become what, in my opinion, is the greatest 007 film of all time, Casino Royale.

Sony could now begin production, and hope to see this attempt through its finish. And of course, they needed a director. Enter Amy Pascal, the then-head honcho of Columbia Pictures. Like Arad, her character will descend into the dark depths of hell and depression and terribly-written mails. But for now, she was steely-eyed about her hunt for a director fit. Her first choice was Chris Columbus (who we know as the Harry Potter guy today). However, in a Transformers movie pitch by director Joseph Kahn, she asked Kahn his choice for director for Spidey. And his answer led to the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

Sam Raimi was, by then, a master of horror. The Evil Dead franchise had become legendary. But more importantly, he had made a successful (and dark) comic-book movie in Darkman. Kahn’s reasoning for his choice was that Raimi’s visual style reminded him of his favorite Spidey artist, Todd McFarlane. It so happened that Raimi was Pascal’s dark horse for the same role. That nudge was all it took for her to cut Sam Raimi a deal a month after meeting Kahn, instead of Columbus.

David Koepp was brought in as screenwriter. The Cameron draft was used as the foundation for the script, but Koepp replaced Sandman and Electro by Green Goblin. No more obsession with having Doc Ock as the villain, at least for now. A lot of things changed about the script, but Raimi was adamant about one little detail, because it would be too unbelievable that NYU student Peter Parker would, all of a sudden, know how to build mechanical web-shooters :)

What’s even crazier is that writers Scott Rosenberg and Alvin Sargent were hired for re-writes and dialogue polishes. The Writers Guild of America credited Rosenberg, Sargent, and James Cameron, along with David Koepp, for the script. The former 3 (INCLUDING Cameron) bequeathed their credits to Koepp!

But sadly, Ted Newsom, the writer of the very first draft, didn’t see his name anywhere in this project. He approached the Writers’ Guild of America with a 25-page document on the similarities between his script and that of Koepp. Only to be snubbed by the Guild. He was fighting that battle alone.

Raimi’s top choice for Peter Parker, based on a wonderful turn in The Cider House Rules, was Tobey Maguire. Maguire wasn’t first preference for Sony, but he impressed executives in his audition. Willem Dafoe got hired as Green Goblin, Kirsten Dunst successfully auditioned for MJ. Dafoe actually refused a stuntman, because he thought that would prevent the body language Goblin needed from fully coming alive on the screen. He wore the entirety of the 580-part suit whenever required. You really need a madman to play another madman. JK Simmons got to know of his casting as J Jonah Jameson in the most J Jonah Jameson way possible: through a fan who read it at a fan website, three hours before his own agent told him. James Franco had auditioned for Spidey, and got Harry Osborn in the process.

The movie was not without its pains. 9/11 had happened during production, so a lot of reshoots took place. Some of it happened in Sony’s Culver City offices, all the way in California. In March 2001, a construction worker named Tim Holocombe unfortunately died because of a production-related accident, for which Sony paid damages. The release was delayed by a year.

But the end result? One of the greatest super-hero movies of all time, the first movie to pass $100M in a single weekend, and the highest-grossing film of 2002, let alone being the highest-grossing superhero movie at the time. Spider-Man grossed $825M worldwide against a ~$140M budget. Even after considering marketing/advertising budgets, Spidey made a net profit of more than ~$400M. Sony announced a sequel almost immediately, to be released in 2004.

If you were in 2004, waiting for the next movie, I wouldn’t blame you if you were expecting a sophomore slump. Not a lot of sequels have been as good as, let alone better than, the original. David Koepp was re-hired, but a difference in vision led Raimi to also bring onboard Alfred Gough, Miles Millar, and Michael Chabon. Like last time, Alvin Sargent (who is Laura Ziskin’s husband) was brought on to polish the screenplay.

Raimi wanted to make a movie about Peter Parker more than he wanted to make a tale about Spider-Man. That should sound boring, right? Right?

Spider-Man 2 made ~$789M on a budget of ~$200M. It broke the original’s first-day gross as well, and also set a record for the highest-grossing Wednesday ever at the time.

It was also critically better received than the first. It got away with using less Spider-Man, more Peter Parker, and a montage of Parker walking to “Raindrops Keep Falling On My Head”. It shouldn’t have worked, but it has now become one of the most memorable scenes not just in superhero movie history, but in all movie history in general. AND it had a great, human, dark Doc Ock in Alfred Molina. Avi Arad, who was one of the producers in the sequel, must have made a killing.

But, you know, if we’re really talking about whether he committed murder, then the next bit couldn’t have come sooner.

There’s a reason I have seemingly rushed this article through the first two Spider-Man movies, and that’s because a) we know enough about how awesome they are, and b) why the third instalment sucked is way more intriguing for story purposes. And Avi Arad is largely to blame for the latter.

According to this interview, Raimi wanted to chart a path of forgiveness for Peter. In his words,

“He considers himself a hero and a sinless person versus these villains that he nabs. We felt it would be a great thing for him to learn a little less black and white view of life and that’s he not above these people. He’s not just the hero and they’re not just the villains. They were all human beings and that he himself might have some sin within him and that other human beings, the ones he calls criminals, have some humanity within them.”

Besides sand effects being more visually appealing, this is also why he decided to include Sandman/Flint Marko, give him a more nuanced background story, and reveal him as the actual killer of Uncle Ben. This would cause Peter to guilt-trip over Marko’s accomplice, who, if you remember, died in the first movie (though by tripping over himself). Raimi wanted Peter to “fall victim to his own pride”, and become a black-and-white symbol of protection, rather than the compassionate soul he is. That would lead him to morally ambiguous acts, and all of this is without the symbiote.

However, Avi Arad wanted the Venom. Raimi didn’t like it, because Venom didn’t fit the template of a sympathetic criminal. He was just a sadistic, sociopathic bloodsucker. Arad wanted a little fan service:

“Sam, you're not paying attention to the fans enough. You need to think about them. You've made two movies now with your favorite villains, and now you're about to make another one with your favorite villains. The fans love Venom. He is the fan favorite. All Spider-Man readers love Venom, and even though you came from '70s Spider-Man, this is what the kids are thinking about. Please incorporate Venom. Listen to the fans now.”

Raimi did a little re-think and did include an un-funny, cocky Venom. Co-producer Laura Ziskin asked him to insert Gwen Stacy, because of how storied her character is in the comics.

I don’t think much needs to be said about how Spider-Man 3 fared. While it did make nearly $900M on a budget of around $300M, it enraged the fans. Venom/Eddie Brock was written poorly, Gwen Stacy had no defining traits of her own, and the promising Sandman was not as well-fleshed out as was initially hoped. In fact, Topher Grace, who played Eddie Brock (terribly), was surprised he was first pick for the role. If I’m being honest, there’s quite some to like about the movie, and even with Arad and Ziskin’s demands, Raimi somehow made Peter’s “pride-downfall” arc believable, albeit with the aid of black goo. And one iconic dance sequence.

Despite the lukewarm fan reception, Sony still wanted Raimi for a fourth instalment, because the $$ was robust. And Koepp moved aside to make room for a writer named James Vanderbilt, who, you should know, wrote one of my favorite movies, ever: David Fincher’s Zodiac. You might want to keep an eye out for David Fincher in Part III, because word is that he’s not speaking to Amy Pascal ever again. And they had a fruitful relationship, too. She co-produced The Social Network.

Anyway, back to Vanderbilt — Sony loved him so much that they wanted him to script Spideys 5 and 6. The story gets murky here as to what Spider-Man 4 was supposed to be. Some say The Lizard/Kurt Connors was to be the villain. Sony was vocal about having Dr Connors as the piece de resistance. Some say the Sinister Six. However, from what I’ve pieced together and what looks legitimate: Raimi wanted to make the Vulture the focus of this instalment. There are traces of a lost video on Vimeo, showing storyboard elements of a battle between Spidey and Vulture. Kirsten Dunst had not promised a return, which got Raimi to insert Felicia Hardy/Black Cat in the script. This could have been real by May 2011.

However — and we might never know how it went down — Raimi wasn’t happy with the direction of the potential movie. He didn’t like the script, and the studio was low-key hoping for old man Alvin Sargent (who wrote Spider-Man 2) to salvage the script. But that didn’t happen. There was in-fighting over Raimi’s choice for the Vulture: the wonderfully-insane John Malkovich. And around January 2010, Raimi broke up with Sony:

“It really was the most amicable and undramatic of breakups: it was simply that we had a deadline and I couldn’t get the story to work on a level that I wanted it to work.”

I suppose Amy Pascal agreed:

“Thank you. Thank you for not wasting the studio's money, and I appreciate your candor.”

But it’s what Raimi said further that really revealed what Sony was planning up its sleeve:

“I was very unhappy with Spider-Man 3, and I wanted to make Spider-Man 4 to end on a very high note, the best Spider-Man of them all. But I couldn’t get the script together in time, due to my own failings, and I said to Sony, “I don’t want to make a movie that is less than great, so I think we shouldn’t make this picture. Go ahead with your reboot, which you’ve been planning anyway.”

And here is where the story of Sam Raimi, a man who literally made my childhood, ends. His whole trilogy continues to be movies I re-watch, and he really didn’t want too much to do with the business side of things. He continues to have a glorious career despite this: he returned to his horror roots with Drag Me To Hell with his brother at the writing helm, with critical acclaim. He made the widely revered and super-funny Ash vs Evil Dead — the TV continuation of his beloved horror franchise.

And he’s returning to Marvel this February in the most magical way possible :))

But in our story, he’s not there yet. Raimi quit the toxic relationship with Sony, but Vanderbilt stayed. Remember how he was tasked to write the 5th and 6th movies? He was actually their backup plan for if and when Raimi wanted an exit. It was his Lizard-focused script that was presented by Avi Arad, Amy Pascal and Laura Ziskin to concerned shareholders to appease them. The foundation of a reboot was laid.

With The Amazing Spider-Man.

This is somewhere in 2010. Spain wins the FIFA World Cup, the Burj Khalifa was unveiled, Instagram was launched to the public, the largest oil spill in Deepwater Horizon happened, Greece was bailed out from a huge economic crisis.

And some science fiction nerd by the name of Joss Whedon inked a deal to make a movie about this ragtag group of 6 superhuman sort of people, named (play trumpet music):

The story of how Marvel came to an Avengers movie is a matter of impossibly impeccable timing. When Iron Man first came out in 2008, nobody expected it to be this good, much less be the first act of a grand opera. But then there was another Iron Man movie 2 years later. Then two separate movies on Captain American and Thor in 2011. It was all coming to fruition and how?

Two men led the charge on this massive experiment, and were effectively the key architects of what we know now to be the Marvel Cinematic Universe. It’s a slight deviation from the Spider-Man story, but they were integral to the insertion of Spider-Man into the MCU.

While Sony was advancing Spider-Man, Avi Arad was making plans to expand Marvel’s movie business. A media executive and investment professional named Amir Malin suggested that Marvel finance its own movies. Arad loved the thought, prepared a huge document called Marvel World, and took it to in-house miser Ike Perlmutter. The document suggested an independent entity, owned 80% by Marvel and 20% by Malin, and that entity would raise capital to make movies on yet-unlicensed characters.

Perlmutter didn’t think it was worth it to throw cash into anything Hollywood. He was certainly not going to give so much equity to a stranger. Ben Fritz’s book The Big Picture has a chapter dedicated to the rise of Marvel in the 2000s, and one quote from there says a lot about Perlmutter:

“But Ike Perlmutter didn’t see the point. If Arad really wanted it, the art department could make one…”

Enter person #1 of those 2 architects: David Maisel. Maisel had the perfect resume: HBS MBA, some time at McKinsey (RIP), a stint at the Creative Artists Agency, then Disney, and a gig with godlike Hollywood agent Ari Emanuel. Emanuel helped Perlmutter and Maisel meet, and Maisel was hired under Arad as the COO of Marvel.

Maisel was a comic-book nerd, too, and believed that movies were a great way to make serious bank. He made a document similar to Marvel World, but minus the equity kicker. Marvel would control its theater releases, which would allow it to coordinate its toy sales. However, the board didn’t find it feasible.

Until Maisel organized an infusion of funds that was the first major springboard to what Marvel is today: a $525M debt round from Merrill Lynch. It is also worth noting that 4 years after this, Maisel led the most game-changing acquisition in entertainment history, which would literally make Mickey Mouse an alpha male. Over Captain America. Over Iron Man. Over everyone that was a Marvel hero.

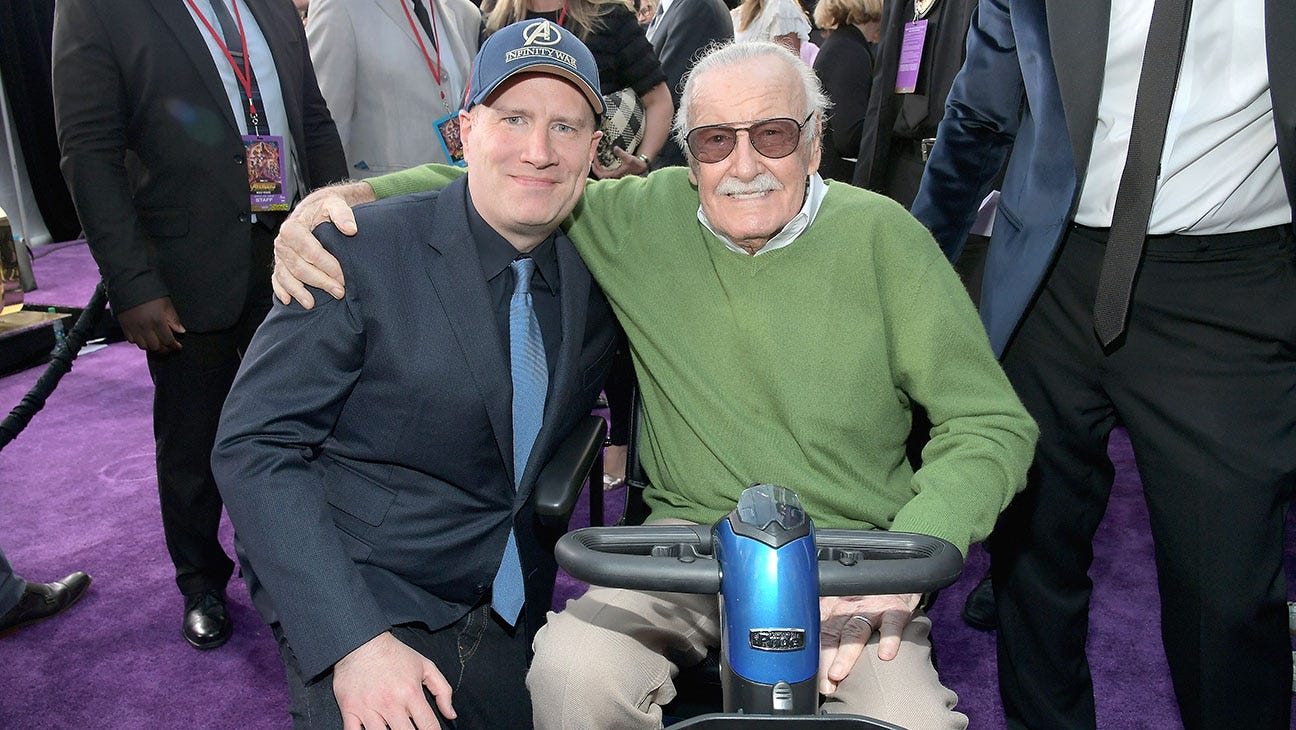

Person #2, who would also go on to work with Maisel and outline the first steps for the MCU, is a happy-go-lucky man named Kevin Feige.

Kevin Feige was a graduate of USC’s film school, after having his application rejected five times. He worked as a production assistant with Richard and Lauren Schuler Donner (yes, the same Richard Donner who made Superman I/II/III), washed cars for them and did every sort of spot boy work. But then, Lauren Donner made an X-Men movie, and Feige was an associate producer on that. That caught Avi Arad’s eye. They had found an infinity stone in him.

Feige was a complete comic-book hog, specifically Marvel. He was a fan-boy at heart. His hero was George Lucas, who also went to USC. Star Wars was his entire life, he knew everything there was to know about it. He had a grounded understanding of what values anchored each of these characters. In a world full of bloodthirsty studios with zero idea of how to make comic-book movies, Kevin Feige was an earnest chap. Arad employed him as his second-in-command, primarily to carry his bags and stuff. But Feige was 26, had his whole life ahead of him, and had a front-row seat to the most exciting deals in Los Angeles.

So now the “chief geek” at Marvel, Feige had a grand vision. He didn’t like that directors didn’t get what drove comic-book superheroes. He thought it was possible to make different inter-linked movies. What if Spidey swung his way into Stark Industries? Not that Marvel had Spider-Man’s rights at the time, but this could be true for any two characters. Or more.

And in 2005, Feige and Maisel conceptualized their own Big Bang for their universe. The first step to that goal was to shine the light on a relatively obscure Marvel character, someone genius/billionaire/playboy/philanthropist-type.

New Line Cinema had the rights to Iron Man for a few years. But they had failed to capitalize on it, and in 2005, Marvel decided not to renew the rights and keep the rights for themselves. However, making an Iron Man movie all by oneself is not an easy task when your CEO is stingy about the fund allocation. Which meant that getting an A-lister to play Tony Stark would have been impossible. Like Tom Cruise.

However, Feige had a make-or-break idea. Why not get someone whose own life story matched the demons of Stark? Why not someone who was a comeback Cinderella tale? Robert Downey Jr — recovering from a serious drug addiction and subsequent fall from fame, and also hot off making Zodiac — was Feige’s first choice. Controversial choice, and probably not worth taking insurance for.

But he showed up in a tuxedo and killed his audition. The rest is history, but the MVP of this was obviously the fan-boy from USC, who we’ll see more of in this story. Marvel was out to compete with the big bad boys in Beverly Hills.

On the other end, Feige’s boss, Arad was fed up of Perlmutter’s micromanagement and extreme skepticism of Hollywood ambitions. He quit before Iron Man was released, and opened his own production company. But as you already know by now; that didn’t mean that he wasn’t involved with Spider-Man.

Step 1 was to get a director. Amy Pascal identified a young Marc Webb, whose biggest claim to fame back then (and even now) was the romantic tear-fest known to us as 500 Days of Summer. It was pressure for Webb, because he was in a situation where he was either going to be in or out of the shadows of Sam Raimi. But he would be stupid to pass such a huge opportunity.

Step 2 was to find a new Peter Parker. Andrew Garfield was always the frontrunner. In an interview with Yahoo Entertainment, Webb recalls the exact moment he knew Garfield was a lock. If you’ve spent your time swooning over the British heartthrob this past year because of his work, you might want to calm your nerves a teeny little bit now. It’s the most Andrew Garfield that Andrew Garfield could be:

“And there was a moment when -- I mean this sounds ridiculous, but it's true. We were doing a scene that's not in the movie, where he was eating a cheeseburger and telling Gwen to like calm down or to -- trying to put her at ease, while he is eating food. And the way he ate this food -- it was such a dumb task -- such a dumb independent activity that you give to an actor to do, and he did it.”

Step 3: In the same interview, Marc Webb also talked about Emma Stone, who was cast as Gwen Stacy. Which blossomed into a lovely friendship, and a short-lived relationship too, between the leads:

“I remember the first time we screen tested them -- I don't think they'd met before, really -- and he took a minute for him to get back up to speed with her because she was so funny. And then they really brought out really great parts of the other's performance. Of course, it was there, and that's why we cast that dynamic. It was really great to watch it on screen.”

Step 4 was to finalize Avi Arad’s brother-in-arms, The Lizard. A Welsh actor named Rhys Ifans, who had been on Deathly Hallows and Notting Hill. Pascal and Arad were determined to reboot the absolute shit out of this.

This is where I end Part II — with how the movie fared. It made good money — $758M on a budget of ~$200-250M. It was….decent. A little repetitive. The Lizard wasn’t as memorable as Norman Osborn. The net profit wasn’t great — $110M, which was 1/4th that of what the first Raimi instalment made, and less than half of the third movie. One reviewer called it “The Notebook in spandex”, but, hey, at least that meant that the core romance of the movie worked. And did it work: Garfield and Stone received unanimous praise for their performances, and Garfield has proved that his version of Peter was as legitimate as any that existed before.

Which at least made things good enough for a sequel. Everything was downhill from this point forward. Amy Pascal had risen to the top of Sony, Kevin Feige had more power than ever, and Garfield loved playing Spider-Man. However, the production of what was to be The Amazing Spider-Man 2 sparked a level of envy and anger that I think only exists in the highest echelons of corporate America. My favorite Andrew Garfield moment ever summarizes what the next few years would be like:

At the centre of the final part of the Spider-Man saga? A terrible sequel that was a natural victim of corporate greed, the most block-busting (and low-key incomprehensible) public mail chain in the history of Hollywood, a huge corporate tussle that spanned 3 ridiculous deals (one of which is Deal 1), and a stupid order to fire an actor because he was too sick to attend a film event.

And, in due time, after all the drama, another innocent, boyish-looking British heartthrob.