A friend once told me that I should be like Ernest Hemingway — write drunk, edit sober. To that friend (and everyone else), a) a fact-check says Hemingway never actually said this, and b) I can’t say I’ve been drunk while writing this, so that’s one cliche avoided. But I hope this piece comes close….in spirit :))

Also: may I recommend a track to accompany this piece. I’m trying an experiment to see what song vibes best with each piece of mine. If you prefer silent reading, that’s great. But if you like your newsletters with your favorite riffs, here goes:

This piece will also require a small glossary:

IFL (BIO): Imported foreign liquor, bottled in origin

CL: Country liquor

IMFL: Indian-made foreign liquor

EDP/EBP: Ex-distillery price/ex-brewery price

AED: Additional excise duty

Gurgaon will take you to the extremes of loving and hating.

The city is a concrete jungle, but unlike New York, it doesn’t have a massive park in the middle. It is possibly the most divisive city I’ve ever visited, or lived in. And I am inclined to agree with either side of this debate.

Divisive, because it’s full of consultants serving their clients at 2 am in the night. Gurgaon was always meant to serve as a corporate hub, which is why it’s not uncommon to notice that loneliness is a common theme among its inhabitants. There is little to expect in terms of natural greenery, except for the inseams of its posh neighborhoods. The weather here knows no balance. At any given time of the year in Gurgaon, you’ll either need a heater or an AC, and spring only lasts for a month. Sector 42 is 6 km away from Sector 43, and rainy season exposes the glaring lack of a good drainage system. The city is not kind to its poor, and it’s as if its slums were wiped. Car accidents are accepted as a norm of living here.

Did I mention politics? Oh, yeah, Gurgaon is home to a surprisingly quiet right-wing residence that rises up in arms when Muslims and Christians try to pray in their own institutions — only adding to the statement that high-paying jobs are not proof of education. All issues Delhi faces, but much worse.

Mini-GTA.

But I have come to like Gurgaon, too, because some of Delhi got passed on to it magically. Much like mini-GTA, you’ll meet some very interestingly weird people, and have weird experiences. You’ll party on weekday nights at your friends’ nice flats, or your own. If you’re lucky, by way of your friends’ cars, you’ll go on gedis at midnight on Gurgaon’s incredibly flat roads. You’ll eat incredible food, although sadly pretty expensive. The online dating scene of the city is thriving, although one can argue that that has its own problems. You’ll live a life of wonderful convenience, and you’ll likely be independent. The city has incredible metro connectivity. And in the worst case scenario, you’ll be not too far from Delhi.

But if there’s one feature that separates Gurgaon from not only the rest of Delhi-NCR, but also most of the rest of India, it’s the city’s raging drinking culture.

One of the first things that I heard when I shifted here was that alcohol in Gurgaon is cheap as hell. I didn’t know too much about retail alcohol prices at the time because I didn’t drink too much in college. Since then, I’ve had more alcohol this year than in the 21 years of my life that preceded it. And it’s not hard to see why: my own place has 3 loaded liquor stores within a radius of 1.5 km, and that’s only the ones I’ve been able to discover in that radius so far.

But you can’t get to having such density of alcohol stores without overcoming some roadblocks. An aversion to an illicit substance like alcohol was a key Gandhian tenet, so much so that it was included in the Directive Principles of State Policy. However, banning alcohol was not a Central prerogative: each state had its own power to decide its rules around liquor.

For long, alcohol prohibition has been used as a means to get a vote bank. Parties would pitch it as a means to reduce domestic violence in households, because who else but men would abuse alcohol? However, in most instances of state prohibition, black markets introduced their ugly heads, and accessibility to local alcohol was only slightly marginalized. Plus, for some states, excise duties from alcohol was a significant revenue head. You can’t do away with that overnight.

Haryana, of course, had a similar political story. In 1996, the Vikas party led by freedom fighter Bansi Lal led a campaign with a promise to ban alcohol if elected. Bansi Lal has ruled Haryana for long enough to be credited as the builder of modern Haryana.

Bansi Lal won the chief minister’s seat, and also delivered on his promise….to zero avail. A cross-border mafia filled in the gap by being in bed with major political figures. Women pretended to be pregnant, children carried illicit bottles in their schoolbags, and milkmen would spike their milk with liquor. Losing the national election seat in 1998 made it worse, along with losing Rs 1200 crore in revenue that had to be covered by raising rates for more essential things. It got so bad that the high court ended up instituting a commission to investigate the aftermath of the prohibition rules. It indicted Bansi Lal himself, and his son, for “creating a situation for smuggling of liquor”. His silence was taken as an admission of guilt, and he admitted as much that criminals were flourishing in this business.

Prohibition had to be reversed the same year. In 1998, then-senior editor of India Today, Sudeep Chakravarti painted a portrait of the day the reversal was formalized. He himself was engaging in the frivolities. Prohibition had improved nothing, and there was skepticism that legalization would, either. But ambitious liquor barons were armed with their bids for allocated liquor vends.

What also benefited this interest from businessmen wanting to make a mark was the state’s lax excise policy. Taxes and duties on alcohol in Haryana are much lesser than that in any other state. In FY20-21, the government reportedly collected Rs 6600 crore in excise revenue and taxes from alcohol alone. For comparison, the total revenue from all indirect taxes was a little more than Rs 45000 crore. Alcohol makes up for ~15% of the Haryana government’s money.

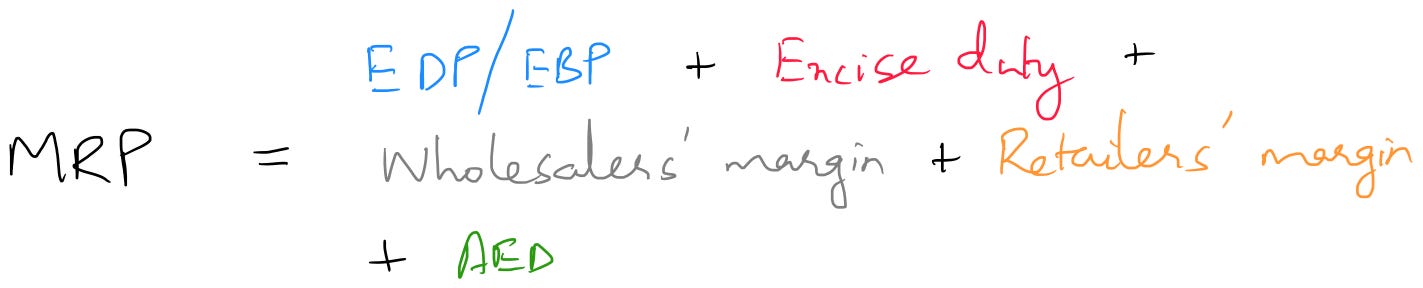

Speaking of excise duties: the MRP of a bottle of liquor can be calculated as:

The EDP, that is the manufacturer’s selling price, is usually proposed by the distilleries to the state government, who approves it. A state like Uttar Pradesh has generally had a significantly higher EDP than that of Delhi — 48% higher, till 2018. In UP’s case, the (huge) profit margin from the EDP went entirely to the distillers, and there was no increase in excise either for the distillers to bear. But that’s a different story that the CAG report linked above will tell you.

Margins, on the other hand, are usually fixed as a % of the MRP (or even EDP), both for wholesalers as well as retailers. There is little leeway there, except for if the distillers sell to the wholesalers at a discount (which happens often). In India, retailer margins are usually set around 20-25% of the MRP on average. Of course — for the same MRP, lesser the excise duty, the better the retailer’s margin.

And since excise duties on alcohol usually cost a bomb, they’re most of the reason why alcohol in Haryana is so cheap. In fact, shops are so competitive here, that there is a mandate to maintain a minimum sale price, but not a maximum. For Indian-made foreign liquor (IMFL), the maximum excise duty levied in Gurgaon on IMFL is Rs 230 per proof litre. It goes as low as Rs 70, depending on the EDP of the bottle.

In contrast, that same number for Maharashtra, till December 2021, was either Rs 300 per proof litre, or 300% of the EDP. Nothing in between. Only in December was it slashed to 150% — still one of the highest rates in India. And even after that slash: a scotch whiskey that’s aged 12 years will cost you around Rs 3800 in Mumbai. In Gurgaon?

Somewhere around Rs 2000.

Liquor in India is broadly of two types: the aforementioned IMFL (like 12 years’ Chivas Regal scotch), and country liquor (CL). Usually, the government reserves a mandatory quota of molasses for the manufacture of CL. This is so that the less privileged can drink cheap & safe liquor legally, and not be dependent on more harmful concoctions like hooch. Some sugar millers aren’t huge fans of this rule: molasses are a key part of the sugar value chain, and a quota would also mean losses in revenue for the millers.

On similar lines, every liquor store is mandated to stock a certain amount of CL. The state government determines this quota on a district-wise basis. It’s safe to assume that rural districts will possibly have higher quotas. There’s a penalty for not lifting a quarterly quota. If, as a licensee, your quota was 25% of your inventory, and you only lifted 22%, two things would happen: a) you’d be penalized for the remaining 3%, and b) that 3% would carry over to the next quarter.

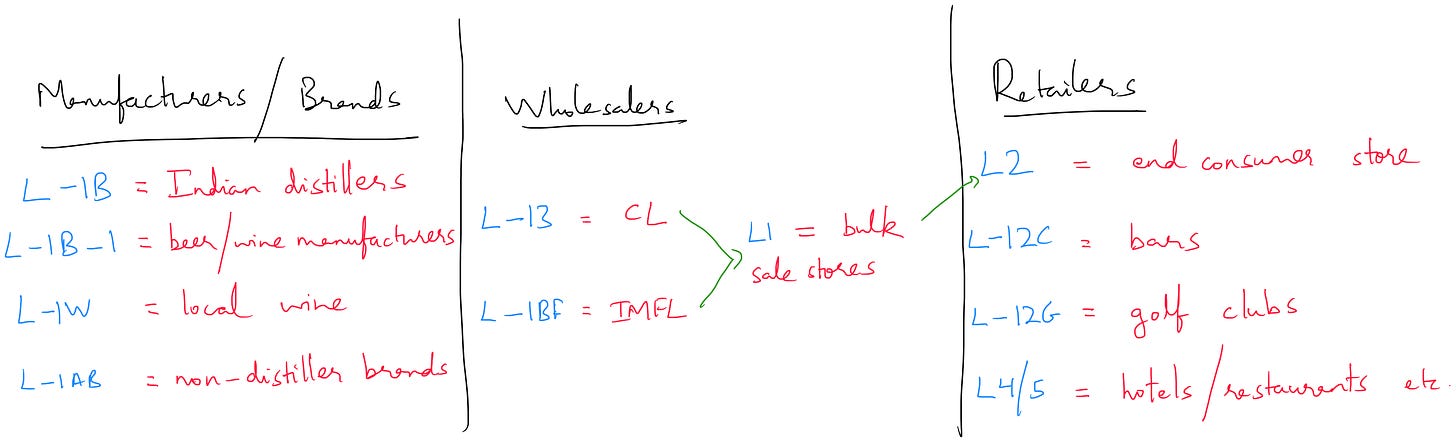

Of course, since alcohol is such a sinful commodity, there is a detailed excise policy by the Haryana government, containing rules for bidding, penalties, duties, and most importantly, licenses. Licenses exist for wholesale and retail selling, and within wholesale exists a breakdown of another set of licenses for different types of liquor. This image might help you understand what I mean, while also revealing an absolutely mind-blowing thing I never knew before:

For the non-Delhi/NCR natives: most stores in Gurgaon are affectionately called L1s. I consider my late knowledge of this a massive personal L. L for license, L for liquor. Nice.

In the image, you have licenses for manufacturers of different types of alcohol to be able to market their brew. They usually sell their stuff to a middleman franchise: major players in Gurgaon who own the entire supply chain, possibly except manufacturing (even that has exceptions). Such players have what is called an L1-BF: the license for imported foreign liquor, bottled in origin. They have licenses to ship country liquor and IMFL to L1s, and then sell it to L2s, or bars (L1-2C), golf clubs (L1-2G), and hotels (L4/5).

To exit an L1-BF — which is not located in a premium urban area — a duty must be paid per bulk or proof litre of alcohol moved. Post-clearance, the bottles are moved to the aforementioned L1 store, the most popular type of store in the city. L1s are usually in very close proximity to L2s. L1s sell to the end customer primarily in bulk, while L2s can sell to the end consumer however they want.

This nomenclature has carried on to the stores themselves. But only L1s and L2s: the last in the value chain, are truly colloquial among Gurgaon natives. And manufacturers are more than happy to spend on licenses. A brand like Chivas will willingly bear a part of the excise duty on selling to an L1-BF — a wholesale liquor storage unit for IMFL that’s not allowed to sell retail — because that would mean money on marketing saved. And Gurgaon is a pretty popular city for pilot launches. I’ve been told that brands have introduced new liquor-based products through the distribution lines of one of these major players in Gurgaon.

And that’s who your attention to be directed to. The guys who own the L1s (or, in some cases, the entire supply chain of alcohol) truly have Gurgaon’s pulse.

Researching for this piece has been some challenge, to say the least. While liquor connoisseurs exist, experts on Gurgaon liquor are few and far between. So what better alternative to that problem than to strike up a conversation with the folks who handle ground operations?

There are three major distributors in Gurgaon: Lake Forest Wines (LFW), Discovery Wines, and GTown Wines — with the first of them being the biggest of them all. Back in the mid-2000s, Gurgaon had only 3 L1-BFs, one of which was owned by LFW. Lake Forest was also the only importer of foreign liquor, from who every other distributor filled their wholesale stocks. Now, the number of L1-BFs in the city are much more numerous: Discovery themselves has around 10.

LFW was founded in 2005 by a Gurgaon native named Neeraj Sachdeva. His family has had a period of living in the US, where they opened up a wine store in the El Dorado Hills in California. The store was named after an eponymous plaza that the first store was located in.

It has an estimated 50-plus L2s in Gurgaon, and one of them happens to be, well, a stone’s throw away from where I live. The store is swanky: brightly lit shelves, with neon-lit hoardings for the brands they host: from the high-flying esteem of Glenfidditch scotch, to the widely-derided scent of Magic Moments — you name it, they have it. Loads of it.

I take a Saturday morning to head over to said store. I talk to the store manager, who has been with LFW ever since its inception, and he remembers back when the only things Gurgaon stores had for sale was CL. LFW seems to have infused the Cali philosophy of how to drink in the Gurgaon crowd. And it’s evident: in 10 years since his induction into this industry, he says that he’s seen IMFL take over completely. And why not? Gurgaon has never been known to be an authentic city. There was a time when this was all barren land. The manager calls CyberHub — Gurgaon’s biggest landmark, for the uninitiated — Singapore-like. While the fact that a city’s biggest landmark happens to be an open-air mega-mall-cum-economic zone reflects pretty embarrassingly on it, it is also reflective of the rapidity of Gurgaon’s development. In a little more than a decade, Gurgaon acquired an envious skyline.

But it’s very funny that he calls it Singapore-like. In an article for Forbes India about Gurgaon’s shoddy city-planning, Pramod Bhasin, who was an ex-vice chairman at Genpact, lamented on a missed opportunity:

“There was a chance to build world class infrastructure and it wasn’t that difficult either. We could have built Singapore. But we didn’t.”

Nonetheless, the fact that Gurgaon has an extremely high number of professionals per square foot area makes it a premium market for something like foreign liquor. And LFW clearly saw it coming. LFW is only now beginning to spread its wings pan-India. But this is a business that has its own supply chain, its own import line, and its own brands of alcohol. I’m told that that LFW sells 1200+ varieties of alcohol, across wine, vodka, beer, rum, gin, and anything else I might have missed.

Earlier, alcohol used to be shipped across the water for LFW. Now, flights have become the preferred, or probably the only choice of transport. A shift to flights might at least indicate faster inventory restocking in lieu of higher costs. But CoVID-19 has blown that hope to smithereens. Fill rate in the past 2 years has been once every 6 months. Orders would need to be taken well in advance. However, foreign liquor companies combining forces with Indian brands would reduce the need for that, since mergers like that would also mean new manufacturing bases in India.

However, while I’m told in broad strokes about how liquor supply works end-to-end, all attempts at asking for figures are trumped. The liquor business is secretive — probably owing to the nature of the commodity. You probably wouldn’t want to know if there was significant amount of questionable lobbying in your Friday Bacardi.

However, the manager over at a Discovery Wines store nearby (read: a stone’s throw away as well) quoted Rs 3-4 lakhs from one store daily, while having around 40 L2 stores. And that’s a conservative figure. Which apparently makes Discovery a million-dollar business purely by sales. Assuming an average order value of 5 lakhs/day/store and 40 L2s, Discovery Wines is more than okay:

But it’s also virtually impossible for someone new to enter this market, because it’s not only oligopolistic in nature, but will also require acute knowledge of how licenses of all kinds work in Haryana. Gurgaon real estate appreciates in value every year, which would also mean that every year, it would be tougher to bid successfully for ground to set up commerce. Especially if that commerce is drinking business. Bids for vends are government-regulated — you’re fighting for limited land allocations, many of which have already been licensed to earlier players.

Both Discovery and GTown supposedly started by buying wholesale alcohol from LFW in its early days, owing to the limited L1-BFs in the city. Both later moved on to setup its own warehousing and corporate partnerships. Discovery also started in the mid-to-late 2000s, but has been through multiple name changes, which might also mean a change in the way they branded themselves, which would also mean that it’d be harder for them to have the benefit of brand recall over LFW. GTown Wines used to go by Jagdish Wines earlier. Discovery has 10 L1s: way ahead from back when they had none. The L2s, as aforementioned, are around 4x that. The manager of that Discovery store confirms a lot of what the one at LFW told me: a much higher preference for IFL (BIO), and a likeness for slightly more exotic drinks like gin and tequila.

There’s still nothing like picking the brain of who’s responsible for envisioning and executing Gurgaon’s consumption trends year in and year out. Someone who’s at the top. And if they are this huge in a given city, chances are their office is located somewhere in the heart of the city.

Sure enough, LFW did. Their office is a run-down building in Sector 18, the road to which is paved with probably good intentions but definitely terrible construction. I have a 3 pm chat with Riya Sachdeva, the head of marketing at Lake Forest Wines. The daughter of Neeraj Sachdeva, Riya started working in the business right after her graduation in the US. She rose up the ranks quickly and is now heading a tight and young team — an interesting departure from an industry that is generally populated with oldies. The two major members of her team present at the time were Anu: who handled marketing and sales, and Govind: a certified sommelier who was her brand manager.

Having young blood, she says, has helped her level LFW’s game up. Pre-CoVID, LFW had little social media presence. Riya has changed that with not only her own Instagram handle, but also that of the company. LFW did a “Break The Neck/Break The Chain” campaign, where customers were asked to break the bottle after finishing it, so as to prevent dilution and adulteration via refills of empty cases. Riya’s own Instagram stories are heavy on promoting the brand of luxury drinking that LFW brings to the city. A major change from a time Haryana wasn’t too keen on allowing drinking be promoted via social media.

The conversation with her reveals the expanse of LFW. The company has two categories of brands:

LFW’s own brews of gin, wine and tequila, that are aimed at the masses @ 900 bucks a bottle. These are manufactured in Chile, Spain and Scotland.

Brands to which LFW has exclusive import rights in India. One such brand is wines by legendary winemaker Robert Mendavi.

LFW’s vastness is also across geographies, with stores already established in Madhya Pradesh, Goa, and Mumbai. Riya is heading an expansion project in Nepal and Kerala (among other South Indian regions). In line with a large trend of Indian firms tapping into a growing Middle Eastern market, LFW is about to open a Dubai office. I get curious as to the cultural and linguistic barriers that a firm based out of Delhi-NCR might face in such a situation. I’m told that that’s hardly a problem, because of LFW’s network across these places. And if you think region and brand were the only factors of its vastness, you’d be off. LFW is privy to a monopoly license to sell to select bars and restaurants, that’s worth a Rs 60 CR annual renewal fee.

LFW is also often a focal point for product pilots by major brands. An example I’m given is Johnnie Walker launching its cocktail mixers. LFW was given the responsibility for distribution of the same. A Suntory, or Chivas, or a Johnnie Walker loves cities like Gurgaon, because they don’t need to do a lot of the market study grunt work to sell their stash. Sophisticated brands just want some prime real estate on the shelves of L1s.

But Gurgaon didn’t turn sophisticated overnight. Retailers like LFW have handheld the city to high-rises of style. For example, Riya tells me that gin is a fairly recent phenomenon: 3-5 years old. Only now will you get to see brands like Bombay Sapphire being embedded in Indian pop culture, and Beefeater and Gordon’s becoming more commonplace. Something that was also confirmed by the managers at the stores I had talked to. Leave alone IMFL, IFL (BIO) has become a fad. Nobody thinks twice about buying a bottle of Black Label straight up anymore.

But that effect hasn’t percolated to every level, including that of the salespeople who pitch bottles to customers. English as a barrier has existed for many thekedaars, which LFW is also trying to change in its attempt to bring El Dorado to Haryana.

Speaking of barriers, Riya is very passionate about carving her own pathway in what is traditionally a man’s world. Under her aegis, LFW is focusing on increasing the diversity of its employee base. She wants more women in her team, and across the organization. She also mentions an incredible support system in the form of women heading marketing at major brands, who give her insights into what sells how much and where. But the team is small so far, with just one other woman besides her. This is visibly a pretty long road.

It’s insane to me how much an alcohol distributor based primarily out of a tier-1 city in India (that’s largely out of touch with the rest of the country) reflects transformation. A decade ago, you would have seen a passionate nationalism towards being Indian, dominantly male executives, a comparatively lower purchasing power accompanied by a hesitation for hedonistic commodities, a bit of and lesser choice in every sense. You wouldn’t expect a legacy industry, bounded by government laws and dated ways of working, to adapt to their environment quickly. But it’s the other way round for alcohol. A quote from one of my favorite movies ever — The Departed, explains it best:

"I don't want to be a product of my environment; I want my environment to be a product of me.”

On the 10th of this month, LFW opened a store that’s 11000 square feet in size — complete with their own parking space, and a sommelier to guide you. Some of Gurgaon’s liquor stores are nothing less than a monument, in terms of size, color, or order value. The video below is proof of how heavenly one store can feel.

But more than anything, it’s key to understanding the rise of Gurgaon as a city of contradictions. Granted, there’s not much to that mental exercise. You have cars here blasting AP Dhillon at maximum volume while getting involved in a super high-speed crash that is likely to result in casualties. You’re as likely to die here as much as you’re likely to have the most fun in your life.

But Gurgaon is home to the some of the most enviable Indian consumer base. And they are blessed to be in the home of, and love — cheap, accessible, beautiful alcohol. Which probably means they’re very willing to buy different things from their monthly salary. The liquor industry is not just an integral part of Gurgaon culture (or what counts for it). It’s also grown alongside the city, which means that for better and for worse, it shaped much of what the city is today.

Until next time :)