Hello, folks! Hot Chips is back, and I think I will end up talking about every food and beverage item before I dive into the one that inspired my newsletter. Some day.

But the piece this time around is about coffee and how we Indians look at it today. It tilts more towards cafes than retail off-the-shelf options, but I had an extremely fun time piecing this story. As usual, I was blown away by what I heard from people and read, and I was constantly learning something new.

However, I drank more tea to get the energy to finish writing this piece. Sorry. Ginger tea is just the classic winter beverage for me. Thank you, Tata Tea.

I didn’t really give too much thought to the backing track, but since coffee table jazz is a thing, I figured I’ll go with one that’s not just popular, but is also a pretty good reading track, in my opinion. Happy reading :))

There’s an entire genre of videos on YouTube that’s simply about a routine day in the life of a management consultant in Toronto/Tokyo/London/insert global city.

Any given video has a set structure: show the consultant waking up, using some face pack product that has likely sponsored them, prep for work, take a cycle, get coffee, reach work, speed-run work….you know the gist. It’s every bit meant to be sold as a glamorous career option in all the things one gets to do as a management consultant. It’s actually a little different from the '“product manager” genre of videos, because at least the poor consultants seem to be on the grind all day.

But this post isn’t about what management consulting or product management is — you can pick up an MBA pamphlet for that. Among creators in either genre — every day, without fail, they go to the same coffee shop, and get that same cup of coffee. And while it’s certainly true for Western countries, you’d be surprised to see that behavior in Indian working professionals, too. The potential for one of us to make “content” around this is not far away — it’s already happening, minus the coffee.

(If my parents are reading this — please don’t pick up an MBA pamphlet.)

India has come a long way when it comes to consuming coffee — from “yeah, I’m good with my Nescafe” to “nope, not touching anything except my morning Starbucks”. And there is still longer to go. But between consumers who are extremely protective about their darling French press, and the professional who can only spend enough time to buy a frappucino, the spectrum of coffee among people who can pay (or don’t care about what good coffee costs) is huge.

This also raises the question of how spoilt for choice we have become, and whether as premium customers, loyalty to that one cup of coffee holds meaning for us. That’s loyalty not just in terms of what the product has to offer, but also what the brand is doing over and above the product to ensure some lifetime patreons.

In order to start this story, we might want to roll back a decade or so, to go back to when coffee started becoming cool, owing to a Karnataka native named VG Siddhartha.

The earliest I can remember being exposed to cafe culture in my tier-2 hometown was a Cafe Coffee Day store. Bright yellow lights, walls with word clouds, “A lot can happen over coffee” having its own space, brown sofas, a counter with some of the most delectable cake and sandwiches I had ever eaten, a verandah for outside seating, and amicable staff. I had not seen this before, because I didn’t know what cafe culture was before this. CCD defined that for an entire generation of people who didn’t hail from a metro, and who didn’t have enough immediate family members who had likely seen the massive green-and-white logo abroad.

And this was by design. Interactions with German and Singaporean cultures made ex-financial services entrepreneur Siddhartha realize that there may be money to be made in selling coffee to people under the guise of providing them with free internet. He decided to move his consumer business of selling readymade coffee to something that might give him more margins — like selling an experience. It’s not like internet was a very widely-available commodity back in the 90s. Sigh, kids these days, cribbing about their Jio Fiber connection snapping for just 30 minutes.

I’m kids.

In 1996, Siddhartha opened the first CCD outlet on Brigade Road in Bangalore. Its biggest draw in a tea-loving nation was its free (but timebound for an hour) internet. While, of course, metropolitan cities would have seen the first spoils, fast-growing tier-2 cities like mine weren’t far away — Bhubaneswar saw its own in the early 2000s. By 2010, there were 1000+ stores all over India — 5 times that of Barista, that had entered India in 2000 with its first store in Delhi.

More importantly, CCD had an otherworldly pulse on what areas in cities were truly popular. As part of their go-to-market strategy, many CCD stores neighbored popular schools/colleges — a cup of cold coffee with benchmates after a dreary day of classwork sounded like the perfect cure. In that vein, CCD had tie-ups with multiple institutes to have a subsidized in-house cafe — multiple IITs have this arrangement. I didn’t realize until writing this that the first store in Bhubaneswar was right in front of the lane that led to my school (and an MBA institute, while we’re at that — please leave me alone).

While Barista is Indian-origin, it always felt like it came from Italy or somewhere in the Iberian Peninsula, owing to the name and the logo. CCD felt very distinctly desi. That logo with the ugly thin font and inconspicuous green leaf that seemed to emulate the French accent over the “e” in “cafe” could only have been a product of jugaad. One look at CCD’s logo today should tell you that the change might have been tough for them.

But while CCD was able to sell the cafe experience to India, it never truly sold coffee culture — even if it sourced beans from real Indian coffee estates. For the longest time, Indians associated coffee very strongly with two other ingredients: milk and sugar. Sure, Barista and CCD explained the difference between a cappuccino and an espresso. But with template optimization over time and scale, you could never tell if you were just having milk with a yellow heart designed on the first layer of the cup. There was quite a blurry line between coffee culture and cafe culture, and there was no micro-level education that was undertaken by any chain at the time to explain the minute differences in cups.

In one way, at the time, coffee was perceived the same way tea was: something to have while sitting and watching the breeze, or chatting with friends. The local CCD store was a premium tapri, if you will, but one that sold coffee. Back in 2008, the average Indian supposedly spent an hour at a cafe — as opposed to a Brit who would be more likely to just grab it on-the-go and average only 25 minutes there.

But Barista and CCD alerted global chains to the possibility of the Indian market maturing to other subtleties of drinking coffee. “I mean, what’s big about offering free Wi-Fi? We could do that too.” English chain Costa Coffee set foot in India in 2005, but not necessarily only with the idea of importing coffee from another country. They found a local blend that matched the one they use in their stores elsewhere in the world. But Costa was playing in uncharted territory: the kind that doesn’t believe in on-the-go coffee. They were trying to do it without a strategic Indian partner, unlike a green-and-white logo brand we know. They were also trying to introduce India to a more premium coffee experience, Italian and all.

For better or for worse, Costa might have been right about its hypothesis on the Indian coffee consumer. After one failed attempt in partnership with the Future Group, that same green-and-white logo finally entered India through a joint venture with Tata in October 2012, opening its first store in Mumbai. The plan was to use the coffee beans that Tata’s estates farmed, thereby solving one end of the supply chain for Starbucks. Apparently, John Derkach — the then-head of Costa Coffee India — once said that he wasn’t afraid of Starbucks’ possible foray, having been used to fighting them in its home country, Britain. But cafe culture had now truly arrived, and this time, the free Wi-Fi was unlimited.

A lot of things have changed since October 2012. Cafe Coffee Day nearly shut shop under immense debt pressure, and turned into how we know it today — a has-bean. Starbucks is gaining significant ground, not just in terms of number of stores across the country, but also in terms of profit. Barista is re-orienting itself to scale stealthily. Costa went through its ups and downs, only to give India another shot with franchise operators Devyani International extending its partnership till 2026. But in the aftermath of the entry of global players trying to bring coffee to India, a few homegrown seeds were planted in the 2010s, that promised a much wider landscape to coffee consumers.

(Something about CCD being that ex that changed your life for the better, but you knew it was time to move on from them.)

India consistently ranks in the top 10 coffee producers. Yet, it usually exports around 70% of all of those beans. A HUGE chunk of the exported stuff — usually 60-70% — ends up being specialty coffee, which is as opposed to instant coffee. There is such a thing as Indian coffee, just that it has been for long largely unknown to regions that were not South India.

This was a gap that Blue Tokai wanted to exploit, and convinced farmers to sell their specialty beans to them, to roast and package for sale. They began operations in 2013, and at the time, they hadn’t started running cafes which they’re now more known for. 3 years later, co-founders Ayush Bathwal, Anirudh Sharma and Sushant Goel set up their own spin on farm-to-cup in the form of Third Wave Coffee Roasters. Sleepy Owl started around the same time, in an attempt to take our eyes away from cold coffee to cold brew, and bring more authenticity to the beverage. And these are only just the popular offshoots of the advent of cafe culture. All of these players were sourcing their coffee primarily from the same region of Karnataka, but found different ways to popularize it. And the battleground was a mix of playing direct-to-consumer, while ideally also opening offline stores. We were finally moving from cafes to coffee.

Cool beans.

Everything Nice

In the grand landscape of Indian coffee, loyalty to one brew is a complex question. I wish I could tell you that it had a straightforward answer. It is not aroma or strength alone that plays into why the average coffee consumer in India is a regular drinker of a certain kind of brew, if they are so. It is a blend of product and non-product factors, while also being limited by the (mis)conception that coffee is also viewed as an item of consumption to be had only on certain occasions.

But I would be wrong if I told you price wasn’t first on that list. Why CCD was able to succeed is because their average price of Rs 150/cup is accessible at once for many people in the earning spectrum. In fact, CCD’s highest-priced serving of coffee, hot or cold, is the (sinfully indulgent) Devil’s Own with cream at Rs 250 — a point that marked the average for other players trying to tap into a loyal consumer base for their brew. For starters, a regular cup of cold brew at Third Wave would cost that much, only to increase with size.

I distinctly remember a friend questioning the need for “fancy brew” as opposed to Nescafe — only to be countered by another friend saying that on a per-gram basis, both cost the same. And it’s true — Nescafe Gold costs around Rs 390 for every 100g, while a pack of Blue Tokai Attikan Coffee beans costs little more than Rs 250 for the same weight. However, naturally, a cup of ground coffee becomes more expensive to brew by virtue of needing to buy the equipment to roast the beans. You may always make the argument that said equipment would be a one-time purchase, but hefty one-time purchases are only useful if we use them regularly. No one knows that better than us thrifty Indians.

More importantly, we are still quite some time away from educating people on what equipment is required to brew those beans. It can be confusing, and a little intimidating at first, to navigate between moka pots, grinders, French presses, drip machines, and good old filter papers. In fact, many of us aren’t entirely aware of how the texture and flavour associated with light roast as opposed to medium.

Blue Tokai understood this early on. A quick look at their website UI tells you that they’re willing to put in effort to make the consumer understand what it is they’re consuming. If you’re a newbie, they have easy pour products for you that just need 4 steps, without any equipment. If you’re looking to have your own home setup, they are willing to offer you a discount on a machine + coffee bundle should you choose to buy both from them. This obsession over ensuring information symmetry for customers is also evident in the notes that accompany each Blue Tokai product — roast level, source, tasting notes — acidity and bitterness levels. And as of this year, they kickstarted something called the Taster’s Club — a series of subscription boxes, each of which is accompanies by 3 samples of 75g, along with a handbook, a video, and access to an exclusive Discord server. Blue Tokai has regular classes on how to brew ground coffee in Delhi, Mumbai and Bangalore.

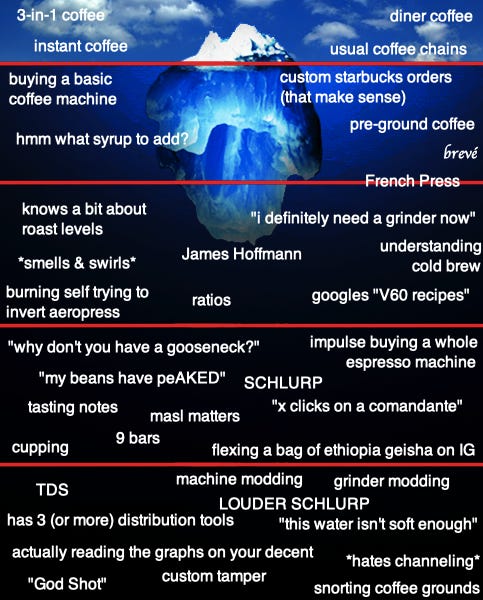

I was almost going to make my own version of the iceberg meme to explain the kind of user evolution Blue Tokai is trying to bring about, but I guess Reddit (from u/ejtc25 on r/JamesHoffman) beat me to it already. I don’t know half of these things myself:

But education is important — not just because it leads to evolution of tastes, but fundamentally for Blue Tokai, it should lead to more money. Blue Tokai operates as both a cafe and a coffee retailer, and as of today, sells the entire suite of coffee products, from the bean to the mean machine. There is always the possibility that they may lose a small fraction of this customer set to more exotic forms of coffee that one may find abroad or in another places in the country — maybe a contact who owns some land at Chikmagalur. But they’re very firm on who their customer is — earns well, likely lives in a metro city, ideally Gen Z or millennial, wants to buy products that align with their values, likes cafes not just for ergonomic purposes (like work or the “vibe”) but also for the actual offering. As long as their product quality is top notch, they wouldn’t need to worry about a fall off. Price is not really an important consideration for Blue Tokai’s target audience, because they believe that the worth of a cup of premium coffee is justified.

It’s a notable shift from the singularity of “cafe culture”, and Blue Tokai is very self-aware about this. In fact, this is an actual quote from co-founder Matt Chittaranjan, courtesy YourStory:

“Our vision has always been to be a coffee company, not necessarily a cafe company. Cafes have been important because that is where people come, try the product, and compare how we are different from the standard coffee available.”

This is also true for Third Wave. If you are interested, on ordering a pour-over coffee, the barista can also show you how the pour-over machine actually works. The off-the-shelf packets also contain tasting notes and roast type.

One game-changer for coffee consumption in India was the pandemic. This was true across the entire suite of coffee products: instant, ground, sachets, filters, equipment. And of course, Dalgona coffee was one of the most popular searches across the internet. It may be safe to say that by virtue of CoVID locking us all down at home, some people might have had more time and money to learn how to brew coffee the way they wanted.

Sugar and Spice

But education is just one aspect of customer evolution, because what is education without scale? A large part of why Cafe Coffee Day succeeded was how effectively and quickly it opened stores, till it opened one too many. Third Wave aims to open 150 stores by March 2023 — that’s 150 stores in nearly 7 years. Blue Tokai, however, had only 50+ outlets by February 2022 — in their ~10-year span. Starbucks crossed the 250 mark earlier this year. But it’s where these stores seem to be concentrated that tell a greater story.

In 2018, Quartz did quite a funnily titled story — “Chennai, home of Indian coffee, scoffs as Starbucks enters the market”. Starbucks entered the city 2 years after it first entered India — which, for a tier-1 city, sounds slightly odd. However, the piece theorises 2 reasons for this delay: a) as protectors of the holy filter coffee, Chennai knew the beverage inside out, and b) CCD alone had 74 outlets in the city. To date, neither Blue Tokai nor Third Wave has a single store in Chennai. In fact, Chennai’s first roastery cafe opened only in 2020, after the first CoVID wave. The story doesn’t just lie in the fact that specialty coffee (or premium instant, in the case of Starbucks) seems exclusive only to tier-1 cities.

Blue Tokai is spread across 10 cities in India, and Third Wave across 8. With the exception of Bangalore and Hyderabad, there’s very little representation anywhere else in South India, or even in the east. Let this sink in: Blue Tokai opened in Tokyo before Chennai. It’s very likely that there’s little reason to chalk this up primarily to CCD’s omnipresence — South Indians just know coffee inside out. And it’s hard to be a coffee store in a city where the people you hope to attract believe that they can do better from the comfort of their own homes.

Which is funny — national stats show that tea outstrips coffee consumption in Tamil Nadu by a mile or two. Ganapathi Ramanathan, a marketer at insurance startup Plum, mentions that coffee has been a marker of caste in his hometown Chennai. After opposition to a Western beverage that could corrupt Tamil women, Tamil Brahmins drank coffee as a status symbol. Tea, on the other hand, was, and continues to be a drink for the working class — Ganapathi sends me photos of how small tea shops exist on every corner even in a city that’s known by the rest of India as a coffee bastion. Coffee hotels took off — with certain areas reserved solely for upper castes. Brahmins developed often-discriminatory rituals around coffee, which eventually crept into mainstream pop culture — and shaped our perception of Tamil Nadu as a state dominated by beans instead of leaves. There’s more in this paper from 2002.

North India loves tea — even if a tectonic shift in its inclination towards coffee began in the early 2010s. And within coffee, instant continues to dominate; being one of Tata’s biggest consumer segments last year. We love our adrak-wali (ginger) chai, and we are unabashed in how much milk and sugar we want in our cup. There is a significant difference in how South India perceives coffee as opposed to other regions of the country — making it a harder market to crack. That tectonic shift that marked an increasing preference over tea for North and East Indians is indicative of a large growth opportunity for coffee chains. However, on the flip side, the misconception about coffee necessarily needing milk has possibly destroyed palettes, and may not be present anywhere else more than in the north.

That being said, Starbucks has 300 stores in 36 cities as of last month. Half of the stores are spread across tier-1 cities. The Seattle chain has also opened at least one store in Bhubaneswar (which has 2 now), Trivandrum, Siliguri, Nashik and Guwahati, to name a few. With the field left wide open after the fall of CCD, Tata Starbucks is looking to crowd in and make the brand name more accessible and ubiquitous. In fact, Maharashtra — which ranked highest in tea consumption in 2017 according to the NSSO — has the highest number of Starbucks stores of any state in India.

And sometimes, expansion is just a question of high footfall. Massive chains literally placed next to, or opposite each other at popular areas in cities like Bangalore and Delhi is quite the “phenomenon”. Below is one such area in Gurgaon that I tweeted about (yes, my tweets often precede my pieces). Similarly, the Tim Hortons in Saket’s Select CityWalk mall, that opened only in August this year, is right opposite the Starbucks there. While all chains have differentiated target audiences, this looks like an attempt to get at fencesitters — with real loyalty to any one brew, yet.

I spoke to Vardhman Jain, co-founder of BONOMI Cold Brew (which, having tasted, I highly recommend), who refers to the popularity of cold coffee, or the Indian version of it — with lots of froth, icecream, and chocolate sauce. A very small niche in India truly understands as a standalone flavourful beverage, and our inability to separate it from sweeteners like milk hampers our taste buds. With BONOMI, that’s what Vardhman is trying to change.

He also tells me an alarming fact that at first sounds too insane: a large portion of India has some level of intolerance toward dairy, but does not know this yet. But apparently, this might have some truth to it, if not all. This may contribute to the idea of palette destruction when it comes to coffee — something that he’s trying to solve for at BONOMI. Moreover, health consciousness became omnipresent in the pandemic, because people realized that life is too short. This is why multiple coffee-related retail startups opened up in the same time — like Kaapi Machines and BONOMI as well.

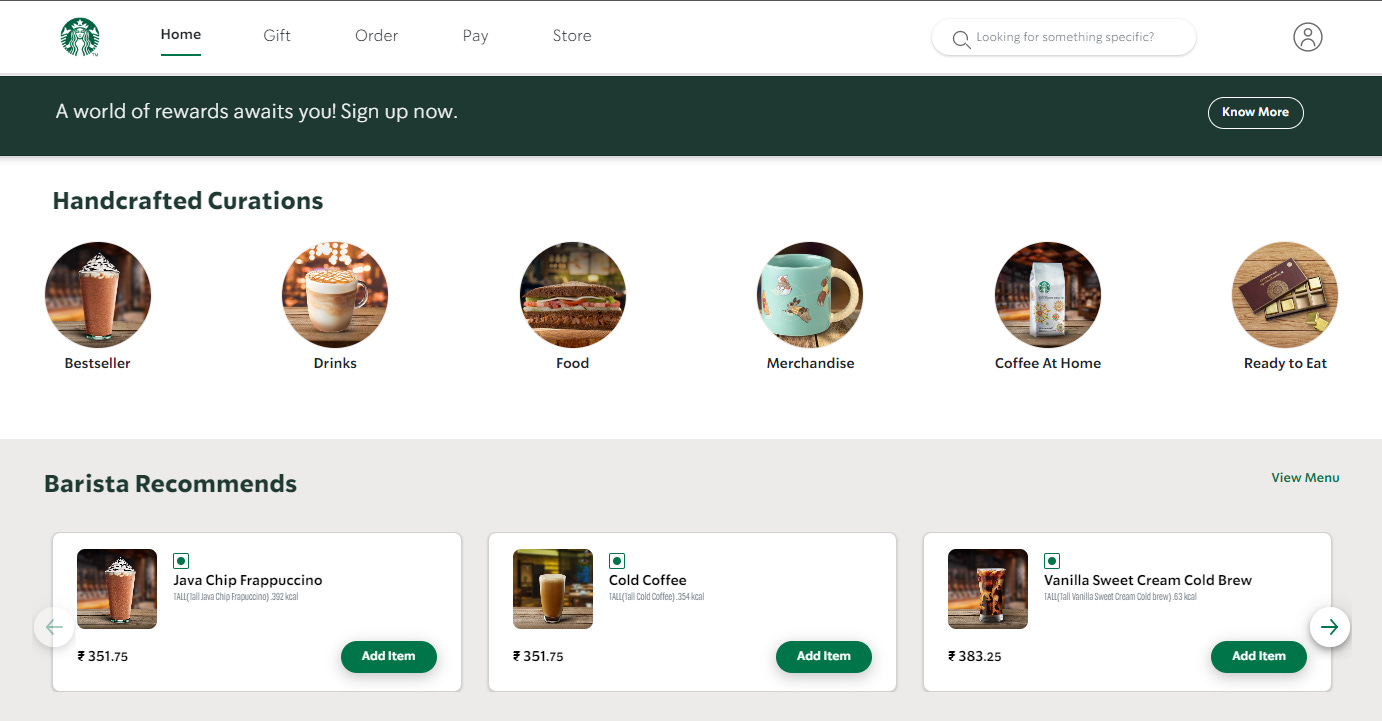

The milk agenda is also something that seems to be pushed by chains. One look at Starbucks’ “barista recommends” proves that much — with the exception of the Vanilla Sweet Cream Cold Brew, every other item is the most indulgent combo of milk and coffee, and sometimes things like hot chocolate. The top 2 items are Cold Coffee, and Java Chip Frappuccino (which is just Cold Coffee with whipped cream and chocolate chips. I assume this dashboard is dynamic, but I don’t expect it to change to purer forms of coffee anytime soon.

Naturally, BONOMI has to constantly be abreast of what its customers like. Vardhman initially thought that his Classic Cold Brew would be the highest-selling bottle for them. He was proven wrong — it ended up being BONOMI’s caramel flavour, simply because it was sweet. After having received training as a barista, and enjoying coffee in its purest, most flavorful forms at different places, Vardhman was primed to introduce the same to a mainstream Indian audience. But it’s tough to sell cold brew that’s not inherently sugar-y in India.

But on the other end of associating sugar with milk is the idea that pure, unadulterated coffee always has to be bitter. Ashwani, the manager of the Third Wave store near Sikanderpur metro station in Gurgaon — one of the prime locations in the city by footfall, says that only 10-15% of customers drink black coffee or cold brew. This niche audience also knows that there is a difference between cold brew and black coffee, and are very likely to be repeat customers in Third Wave for the very same item. This is also a sentiment echoed by Vardhman, who often finds himself trying to explain the difference between cold brew and iced coffee. Or that coffee doesn't always have to be bitter.

Prathiksha BU, a reporter for YourStory, fits the ideal consumer for a lot of the pro-arguments for spending good coffee. Her hunt for good coffee came from her dislike (not necessarily intolerance) for milk. She tells me that she was not the biggest fan of filter coffee brewed at her family home either, simply because of the existence of milk and sugar in the final product. She started learning brewing her own beans from people in the industry, and also invested in equipment to do the same at home herself.

Welcome to the Working Week

There’s little doubt that coffee is quite a nice and complex beverage that deserves its own little time slot to enjoy while sitting in the balcony without any other distraction.

Assuming that’s true — it’s pretty insane that it’s become widely accepted that we find that our work has to accompany our cup of coffee. Those “day in the life” videos are the most popular exemplification of this.

Besides Red Bull/Monster, coffee is the go-to for people who need a productivity kick. And cafes have turned out to be a boon for people who need a space to work, and a good cup of coffee. But over the years, it’s become harder to decouple the relationship between coffee and work. It’s as if our idea of coffee consumption is increasingly defined by how we choose to work. It’s no coincidence that coffee culture in India has progressed pretty much hand-in-hand with its tech ecosystem.

Abhishek Shah, the founder of an early-stage e-commerce startup named KURA, is quite the frequent visitor of the Starbucks near his house in Mumbai. He tells me that he’d give Starbucks a 5 or 6/10 for the brew quality, saying that he’s certainly had better coffee. But one of the core reasons why he goes there almost every day is because it’s significantly cheaper than renting a co-working space, especially in Mumbai. He doesn’t use this Starbucks, or any Starbucks in general, for a social reason. For that, he prefers to visit indie shops, like The Bagelshop in Bandra. He adds that whenever he sets up an office space for KURA, he’d want freshly-brewed coffee every day — much like the Blue Tokai he makes when he can, and not the Starbucks that he finds convenient to go to.

It’s not tough to imagine coffee as a function of your profession. I speak to Ankit Kumar, who works in the product division of a company that — and I swear I didn’t realize this until I wrote these words — BREW.com. Working in a remote job allowed him to explore a lot of cafes in any given city that he stayed in. But at the same time, it’s also the type of establishment he goes to almost every day to do focused work.

His morning cup comes from a cafe near his place of residence in Bangalore, called All About Coffee. He has taken the black coffee redpill as well, having moved to loving the Americano more than the iced latte. My conversation with him indicates that certain cafes have different purposes for him. He looks at the cafes that he frequents for work as a ROI problem — “X is what I earn per hour. If I’m paying 200 bucks for 4 hours of productivity, what’s the return I get on my salary?”

And some cafes are, of course, deliberately designed to be productivity-friendly. Third Wave Coffee has a dedicated in-house design team, which ensures a couple of things: a) every store screams the brand’s minimalist approach, and b) there’s enough plugpoints in the entire cafe. Third Wave initially started by gathering micro-communities of people across different professions who enjoyed coffee. But in the last couple of years, especially with the boom that India’s startup ecosystem has seen, the chain became singularly known on social media as a productivity space. This is also one reason why Nikhil George, a fintech professional based out of Mumbai, prefers to go to Starbucks over some other chain — plug-points.

In metro cities like Mumbai, Bangalore and Delhi, our enjoyment of coffee also falls victim to convenience. There is no way anyone in either city is willingly wading through traffic (and smog) to go to a fancy cafe to have your work be accompanied by some incredible coffee. And on the days you’re not working, your will to explore is a little hampered by those same factors that define a city’s flow.

Utility, not experience.

Image is Everything?

Bigger chains capitalize on this idea of ease for the sake of productivity not only by expanding quickly across India’s prime locations, but also ideally by introducing a loyalty program. Both Starbucks and Third Wave have loyalty programs that are designed to retain regular customers. Interestingly, CCD was a pioneer of coffee loyalty programs in India, with the launch of the Citizens’ Card in 2002. This evolved later into earning “Beans” on the CCD app, which was launched in 2015. Barista launched its own “Bean ‘o’ holic” loyalty card in 2012, with consumers graduating levels by accumulating points with every purchase. Costa has an app for loyalty too.

How effective are loyalty programs overall? While it’s not known how successful that has been for most other chains, Starbucks’s loyalty program has been killing it in India — with users increasing significantly year on year. It’s the promise of rewards on a set number of repeat purchases, and the idea that the average cost of your cup of coffee dips with time through discounts. However, it’s not difficult to have the apps of different chains on your smartphone. You don’t necessarily have to pay anything beyond a cup of coffee to install loyalty apps.

Which is where Blue Tokai differs — it prioritizes discounts online subscriptions over out-and-out loyalty programs. Sarthak Rastogi is a venture capitalist at Gurgaon-based Huddle, whose portfolio includes Blue Tokai. He says that Blue Tokai knows its customers really well, who, unlike for other chains, also buy Blue Tokai’s off-the-shelf products in bulk. For them, investing in education has been the more important method of customer retention than any sort of loyalty schem Its customers are looking to migrate to a top-tier level of coffee, ideally never to look back on the artificially-sweetened products they were once used to. They understand what the brand of Blue Tokai stands for, and why so.

This raises other questions about brand perceptions. Why did Dalgona coffee get a bad name from coffee connoiseurs at the height of its popularity in 2020? Why is CCD sill so revered as the spot for a lot of “first” experiences? Why is Blue Tokai’s logo a peacock? (To that last question, they have a cool story about “tokai” meaning the plume of a peacock — the national bird of India.)

But adding to the idea of brand perception is a conversation with Tejas Kinger, a product marketer at Plum. He says that even though he can certainly afford it — and has spent a lot on experimenting with different coffee brands — entering a Starbucks continues to feel a little intimidating. This may have something to do with looking at it as an aspirational brand while a college student. A sentiment that Ankit also shared — spending a fraction of his first internship stipend at the nearest Starbucks store is a memory he remembers.

And image is everything, especially when it comes to getting new customers. Starbucks attracts aspiration, Blue Tokai evokes purity, Third Wave recalls utility, CCD is comfort.

This is also something that a brand like Tim Hortons — that entered India only this year with its pilot stores in Delhi/NCR — understands deeply. “Cheaper man’s Starbucks” / “Canada’s Starbucks” is the most common moniker that you could hear on the aisles of CyberHub in Gurgaon, where Tim Hortons first opened this August. The line to enter the store was long every day for at least the first 2 weeks from the store’s opening. More importantly, Tim Hortons left no stone unturned in cashing into its Canadian heritage — opening its third store recently in Chandigarh. They’re looking to be an aspirational brand, much like Starbucks, but a little more affordable. An increasing market size for coffee, especially among Gen-Z and millennials is something they’re banking on. It helps that their emphasis on literally painting the town red reminds one of Christmas.

The Fourth Wave

India is well into the third wave of coffee right now — where the story behind the beans has become more important than ever. The quality of the bean is important, and the consumer should be able to manipulate the bitterness and texture of their drink. More people are slowly realizing that the coffee bean has so many form factors that they can’t, and shouldn’t be one single template way of enjoying the drink. Coffee doesn’t always need to be heavily roasted, and light roast beans go extremely well with other flavours — especially citric ones.

Specialty coffee players that have expertise in the end-to-end of the single-origin coffee bean have emerged in small numbers in metro cities. Fermentation of coffee seems to be quite an experiment that some of these roasteries are trying out their hand with. There’s Maverick and Farmer, that created a fermented brew with orange juice. They have 3 cafes spread across Bangalore and Goa. There’s Mumbai-based Subko, that offers a cup with notes of maple syrup, apricot, and pecans. This natural extension of the third wave is — a) focused on expanding the science of coffee by extracting the most out of coffee beans, and b) commercializing this science by taking it to homes. In the most ideal state of this phase, coffee is not associated singularly with bitterness or sweetness, specialty blends become more accessible to homebodies, and large cafe chains have much less of a hold.

The issue? Growth for such coffee is pretty slow. Vardhman says the same for BONOMI — that the move away from his sweeter flavours to more exotic ones is happening, but not as fast as he thought it would be. Maverick and Farmer closed their Gurgaon cafe permanently — proving that it’s tough to sell the idea of experimenting with coffee to a city that breathes on constantly moving for work, among other harmful substances. But notably, the idea of coffee being more flavourful also coincides with its health aspects. Post-CoVID, the most popular question Vardhman gets asked is regarding the calorie intake and sugar level in his bottles.

India is also trying to create a name for its beans globally. Blue Tokai has entered the Japanese market. Roasteries like Subko trying to sell their single-origin experimental brews sourced from their micro-estates to the world — like coffee with lychee candy. They’re also explaining why growing coffee at different altitudes is different, among other nuances. Coffee-based cocktails are quite suave, too, although beyond the occasional bar, there has never been an attempt to make them mainstream.

In a lot of ways, the stage for such artisan cafes / retailers has been set because of the advent of Blue Tokai’s transparency in its packets — what’s the origin of the bean, how bitter or acidic it is, etcetera. The move to specialty coffee will depend on how India’s income levels grow in time. Making your own batch of coffee at home can get fairly expensive. Even more so when you like exotic flavours.

But it may be safe to say that we’re getting used to cafes existing because they have more to offer than just their aura. And we wouldn’t likely be here if we hadn’t been graced by the funk that CCD brought. The best way to look at summarizing India’s journey and perception towards the beverage lies in CCD’s tagline. We went from “a lot can happen over coffee” to “a lot can happen around coffee”. For a country that had little knowledge outside of pockets as to how much we produce coffee, our graduation into coffee culture necessitated the precedence of cafe culture. Coffee culture is staying for the better, and is most certainly evolving.

Until next time :)

Special thanks to the following people who made this piece happen: Vardhman Jain, Sarthak Rastogi, Nikhil George, Anagha K, Ganapathi Ramanathan, Tejas Kinger, Prathiksha BU, Abhishek Shah, Ankit Kumar, Siddharth Vijayaraghavan!

I’ve been simultaneously sort of doing some groundwork on my next edition — I have known for a while what the December edition is going to be. It will be my most ambitious piece to-date, which also makes it significantly harder to pull off. If everything works out, I’d love to show it to you as soon as possible!

Woke up to smell this coffee - delectable!

No connection but, reminded me of the line ' I have measured out my life in coffee spoons...' from a poem called The Love Song of Alfred J Prufrock :-) And no, I didn't pick up the MBA pamphlet!

Don't like MBA Pamphlet. theek hai, Booklet coming your way...