numbers on the boards: how data is defining art — part II

(My music-pun title game is peaking)

Earlier this month, good samaritan platform Bandcamp supposedly banned ambient music from its platform. Some representative from the company apparently said, “That ambient shit doesn’t even slap”. Clearly, said representative doesn’t appreciate the sleep-inducing qualities of Aphex Twin (and I mean that in a good way).

It’s also definitely a joke from the tweet that said this: where else will ambient exist?

But what’s funny is that this happened in the midst of me researching for this very piece, which asks one question:

“How is data changing the music landscape, for better, or for worse?”

We’ve all done our bit in complaining about Spotify’s terrible payout rates, how much Spotify knows us better than we know ourselves, artists increasingly making shorter songs, and music being a thankless business if you’re not already from the privileged class of your region. Those things are true, but I wanted to look at them from different POVs. First among those, of course, is checking out the money trail.

Alexa, play Money Maker by Ludacris, while I dive headfirst into this megalomaniac, wondrous structure of systemic thievery.

In the interest of keeping this piece crisp and cool, I made a few diagrams to illustrate the payout system in the music industry. If, like me, you freak out at my diagram/the sheer rabbit hole this represents, I promise to make the explanation smoother.

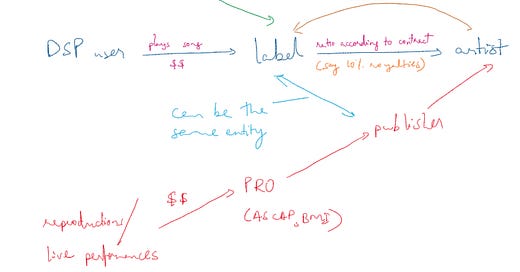

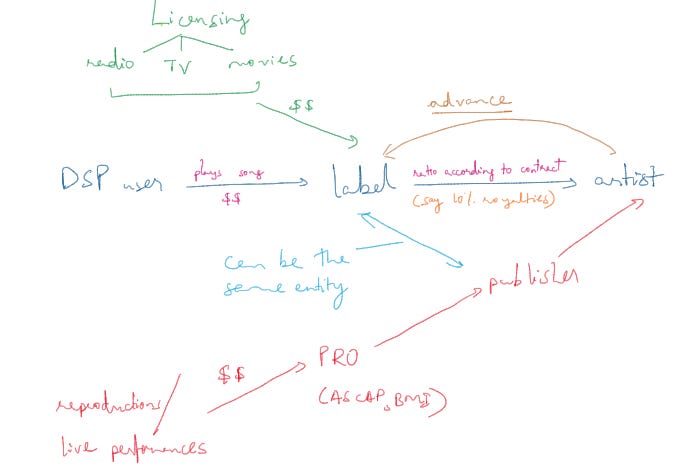

The diagram shows three sources of revenue: licensing, streaming, and reproductions, and the payout pipeline to the artist. Usually, a stream is also considered a “reproduction”, but you can imagine how streaming must have created an upheaval among music labels to change their business models overnight. For convenience purposes, we take streaming and reproductions differently.

The payout pipelines of all sources are significantly different. Assuming that the artist has a label’s backing — they get paid an advance to begin with. The label handles distribution, marketing, studio time, legalities (especially with copyrights) etc. It takes a significant chunk of the streaming dollars because in essence, the label is taking a risk or a bet with that artist. There is a possibility that the artist doesn’t generate enough money, and that’s a tank for the label. That risk lessens with how big the artist becomes, of course. Artists get paid in a ratio agreed upon in a contract after the advance is recouped. Royalty rates can be very mediocre, and the bigger the artist, the more the bargaining power. At the end of the day, the label owns the master — the original song, in all its glory. A label is a contractual burden. You are expected to roll out a set number of albums/EPs to fulfil your obligations.

A PRO — performing rights organization is usually a non-profit that helps manage money from live performances or reproductions/covers. Artists hire publishers to manage revenues received from that end because PROs have no incentive to manage those for you. Bigger labels usually have their own publishing houses.

I’m sure you’re wondering — “What the fuck?” Yes, Frank Ocean and Taylor Swift bypassed this entire black box to become the megastars that they are today. And this entire structure gets hairier when you have featured artists on a track, or multiple songwriters. Think of all the songwriters on a Sasha Fierce-era Beyonce song that had different representation. Or better yet, Kanye West’s All of the Lights. A hip-hop beat becomes worse — if there was a drinking game for hip-hop songs whose releases were delayed because of a sample issue, I’d pass out, wake up, and find out I have a kidney problem, in three hours, tops.

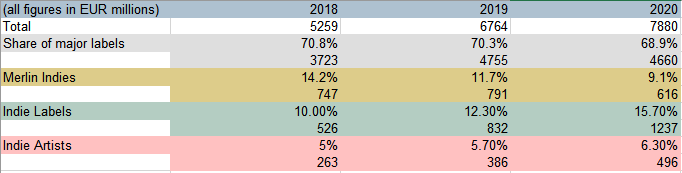

While you could argue that T-Swizzle and Ocean had the power to call shots, there’s an argument for digital streaming platforms (henceforth DSPs). Today, indie musicians have access to middlemen platforms like DistroKid and TuneCore, that, for a flat fee, get your song live. However, this black box warrants a significant amount of marketing, that is difficult for an indie musician who doesn’t know how to track key metrics for the success of their content (we will come back to this idea later in two ways). The good news is that there has indeed been a rise in indie musicians every year. The better news is that revenue from indie music has seen solid growth, too. However, like all good things, there are roadblocks to this too.

Revenue growth for independent artists alone is itself growing at a snail’s pace. Indie labels are soaring, while Merlin indies are falling. I have a feeling that a number of indie labels were able to crack distribution profitably without needing the Merlin subscription. Major labels, however, not only lost share, but their streaming revenues actually fell last year.

But 2020 was definitely a strong year for indie artists. Look at India itself, with the advent of Anuv Jain, The Local Train, Prateek Kuhad blowing up. The love of all party-popping North boys, Sidhu Moosewala, uploaded his 32-song joint, Moosetape, directly on Spotify (he’s had label affiliations before this). He did this in May 2021. 3 of his songs continue to trend in the India top 200 as of last week. Then of course, you have Ritviz and Nucleya, Taba Chake; some of India’s most popular artists are indie.

Spotify usually pays royalties worth 65–70% of its revenue, which….sounds like a fairly decent figure? But then Bandcamp pays in the 90% region, and Spotify’s average payout doesn’t justify this figure. The rest of it money goes into fat salaries, research, UI/UX. It must have spent half its marketing budget in India’s premier universities.

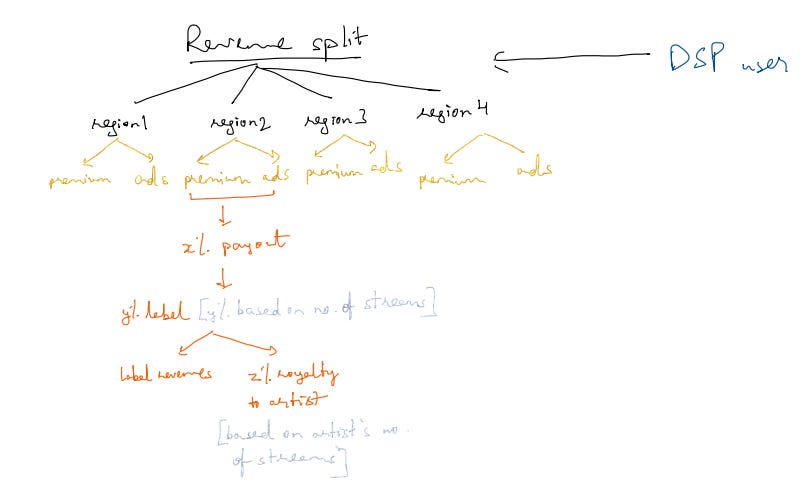

Then beyond the label’s cut, what’s the deal with these shitty payout rates? We’re going to find out why, using another “Pranav Manie threw Cs in his art class” diagrams. Side note: this is where you figure out how your Spotify premium money gets distributed.

If you were an American premium user, your contribution would have had more worth than if you were an Indian.

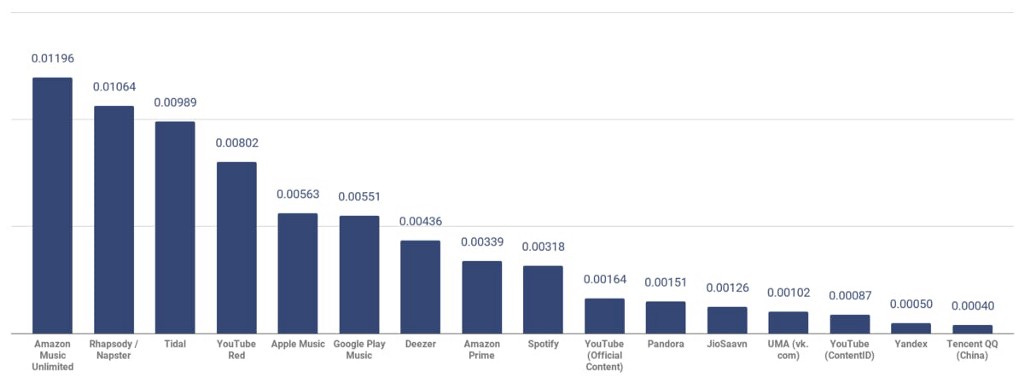

How much an artist receives as payout depends on a) the revenue pool of their region (because pricing plans vary), and b) the number of premium and ad-based users — more premium users, better payout. The average payout per stream is $3.20 for every 1000 streams. So if Blinding Lights, the biggest song of 2020, has 2 billion plays, The Weeknd might get on the higher side of $3.2 million, given his region. However, payout doesn’t happen per stream, but from the pool. That rate will depend on who you are — who your label is, and what your royalty cut is. India’s plans are cheaper, and not a lot of people are willing to pay. That dilutes the overall payout. This is also why YouTube has pays really low, and Apple much higher than its competitors.

All said and done, Spotify’s net profits are usually negative every year. I imagine that their key problem statement right now must be: “How do we get free [and modded :)] users to pay for premium?” This is where a conversation with someone from a label led to a fun insight on what the premium stands for: you’re paying Spotify not necessarily for the music, but for removing the ads. And they have been playing a long-term game for increasing the free-to-premium funnel — podcasts.

It all began with making exclusive the most popular podcast on YouTube — JRE. Elon Musk, drugs, memes, political incorrectness. If you didn’t know better, Joe Rogan and Twitter are the same entity. When data says that people don’t like being told how to be more woke/nuanced, Spotify threw down its money there and paid Joe Rogan buckets to upload only on Spotify. In India, that deal was BeerBiceps. The top 100 Indian entries on the top podcasts of India are littered with those names: BeerBiceps (English and Hindi), Yours Positively, Finshots, Ankur Warikoo, Jay Shetty, Josh Talks, Sadhguru, and Naval. Many of these aren’t exclusives, but I bet 100% you can already imagine the user persona that absolutely devours podcasts every single day. There may be new podcast deals at the intersection of self-help and entrepreneurship and business in the future. Spotify has been making massive podcast acquisitions, biggest of all Anchor, that it is now using to help podcast creators monetize content using paid subscriptions. It also launched “Sound Up” for women podcasters.

You’d have to wonder where Tidal went wrong. Tidal was music utopia. The greatest musicians of the industry saying “fuck you” to all other DSPs at $10 for every 1000 streams. But it failed to pay the labels on time. It did a little number fudging for Beyonce and Kanye because more streams means better pay, the same system as above. Of course, American cowboy Jack Dorsey bought Tidal out, through his fintech baby Square, for some interesting NFT play. Bandcamp , though, is proving that respectable payout for indie artists are indeed possible— on Bandcamp Day, indie artists earn revenue in thousands of dollars. More than they might on every other DSP combined. And it’s catering to a group that stands in stark contrast with Tidal’s.

This is also where I do a little segue into what I really want to talk about (and why I used NFTs for the segue): how do you….escape this? Sure, streaming has made things easier from an entry point of view. But if you’re an indie artist, or part of an indie label, you’re going to face an uphill battle on legalities, content marketing, merchandising, and so many other factors that a major label would handle for you. Labels can help you have content teams (told you I’ll come back) that tell you, a musician, what TikTok trend or meme is cool now so that you can capitalize on it. This exists: look at Badshah, making music on the “Bachpan Ka Pyaar” meme. He might have done it himself, but imagine the time investment it takes to capture trends besides songwriting (I was told that he did do it himself, apparently). Oh — labels are recruiting lo-fi artists [Yes, the guys they love striking down on YouTube]. To make covers of the masters they own. This is what Sony Music has done with VIBIE, ever since Bollywood slowed + reverb covers became popular. They have more lo-fi releases in the pipeline.

In short, they’re going with the flow of the entity whose identity we only know as the Algorithm, that begins its journey in YouTube’s recommendations, and ends in Spotify making doctoral prescriptions for you every week.

It is harder today to create awareness of your own unique sound at mass scale. The fact is that Prateek Kuhad has had many copycats, because they know that people love that soft bar vibe. Maybe do a guitar-only song. Labels will actively recruit such musicians, and at some point, their A&R departments won’t even have to hunt too much. Copycats are not new — we see them all the time in rap. But streaming has a multiplier effect.

I don’t raise these points merely because I think the story ends here. If anything, I’m way more positive about music business in the future than anything else I’ve written on, because a lot of what I’ve written above also displays scope for innovation. There’s a reason why I used NFTs to segue into innovation. As much as I am still skeptical about NFTs, a musician could always use market economics and bullishness for NFTs to net some money for oneself. But using crypto-tech is not new to music. A few years ago, apex British crooner Imogen Heap launched Mycelia, a blockchain-based music solution for artists to protect their rights by maintaining metadata, and receive full payouts on plays. Recognition in the music industry is apparently a real problem, so along with money pinches, Mycelia solves that issue too using their Creative Passport ID.

But let’s not crypto-tech carry away things like it always does. How do you help musicians crack the marketing game without investing in a label? Can there be small agencies that help them perfect performance and content marketing? What about deciding what channels are right? What about getting an artist to, ahem, “build in public”? Few things get people more interested than behind-the-scenes footage. But these are just ideas from someone who doesn’t know marketing. How do you better utilise TikTok, Instagram, Bandcamp, Twitch, to get yourself hype? Heck, Perfume Genius has a Substack.

How do you discover music better? I have friends who have incredible music taste, and they know artists I’ve never even faintly heard of. Despite Spotify, I still have a WhatsApp group for music recs, because listening has a social element to it. The algorithm necessitates such groups in a way, to listen to things beyond your circle. Of course there are startups there to fix a nail here. I’m currently hyped about humit — India’s own social music app, that also got some pre-seed funding by Antler’s India fund this year. I only recently got hooked onto it, and it looks super interesting! There’s Earbuds, whose USP seems to be letting famous people share their music, among other features creator monetization & commenting on people’s picks. There’s ByteDance’s Resso — Spotify and Snapchat created a car together and added TikTok’s chassis to the body. Spotify isn’t stopping — it recently launched Blends, that makes playlist out of the picks of you and a friend. It rolled out Music + Talk, that lets you experience being a DJ — speaking as you play the next song on your rollicking playlist. May I also suggest some SoundCloud & Bandcamp integration with social apps?

Merchandise! This is probably the easier part of it (as compared to the above two), what with the number of new startups that sell their own customized clothing. Seedhe Maut has a clothing and accessories partner in Supervek. AP Dhillon is releasing his line with SenPrints. Usual suspects for official merchandise include Redwolf and The Souled Store. This reminds me — I do need a Prabh Deep, or a Seedhe Maut tee.

Lyrics! India doesn’t have an alternative to Genius, and Musixmatch is poor when it comes to Indian music of any language. Crowd-sourced lyrics with annotations is the best way to go in my opinion. Of course I want to know what AP Dhillon is saying in Punjabi, even though I know that he’s pretty much Drake in terms of his subject matter. Tamil and Kannada rap are coming up. I need lyrics to it, and I need to understand them, and I need one source for all such songs.

Legalities. A conversation with the same friend at the label also enlightened me to the fact that musicians have trouble navigating copyright and patent law. Doing that is more than half of the job, at least in terms of royalties and ownership. I’m too afraid to say that blockchain can solve this, because it’s such a bad cliche to assume that it can do anything that isn’t being done right now. But the technology does offer smart contracts, protection from tampering, ownership of distribution and licensing rights, automation of royalty payments. Maybe, blockchain could finally prove me wrong when I said it was the most over-hyped technology of the 2010s.

I had a killer time writing this. It was a mix of most things I truly love to talk about: music, business, and music business. I can only hope that each of those things gets truly democratized with time. We went from records, to CDs, to reproductions with no physical presence. We pay much less for music today and enjoy more music than we or our parents could. We don’t need to torrent things, and we will likely not see scandals where metal bands sue DSPs for ripping off their music. We gave our listening (and watching) habits priority. That changed the data landscape. It’s a feedback cycle, where we provide the data, and get provided with more data ourselves based on what we sent out first. Ironically, instead of keeping us within, that cycle has created new lanes for innovation.

In short, ambient music will be here to stay, with or without Bandcamp.