paint-by-number: how data is defining art — part I.

There was a ton of sex this past year.

I apologize for the opening, but this is less clickbait-y than it seems. As a collective human species, we probably couldn’t satisfy our base desires to the fullest extent in the pandemic. But I still meant what I said. I should clarify, though: there was a ton of sex on TV.

The pandemic provided for the opportunity to try out an interesting uncontrolled experiment among the users of streaming platforms — what content do we think works? It may be a stretch to say that this was a prospective move rather than a retrospective one: Netflix usually depends on data from organic platform usage rather than data derived from, say, A/B testing. That still doesn’t change one of the most important facts of media consumption in the pandemic: it was a Polish-Italian erotica thriller that is credited with the unique feat of reclaiming the #1 spot on Netflix after slipping from the place, twice. All of that also happened in the span of about two weeks, beginning its release data — June 10. It’s an intense, controversial movie called 365 Days.

But we’ll come back to what this might mean in a bit, because this Forbes article allows me to diverge into another one. Forbes writer Travis Bean created a simple tracking system that allows to chart performance of movies on Netflix (who is notorious for not giving us any consumption data). Apart from the fact that Netflix-produced movies don’t dominate the top 20 movies ever seen, what else strikes to you when you look at it?

Yep, lots of animated movies. He had a small time-period consideration for the system (Feb to June 2020), hence slightly unreliable. So I decided to cross-check it with stats for 2020 overall from FlixPortal. There’s tons of movies, but children’s movies prime amongst them. It makes sense: from my own sanity check and a few estimates I’ve seen (please give us data, Netflix), there should be around 4.5 million Netflix accounts in India. Almost all of these will be shared/family accounts, with an average of 2 children. And this is just India. Imagine a country where Netflix has insane penetration, like the US, and transport the same logic there. It also makes sense from a competitive point of view: one of their bigger threats happens to be Disney, who owns some of the most heart-endearing pieces of innocence.

Anyway, back to sex. What’s the most popular, most viral movie on Netflix, from all of last year, according to FlixPortal?

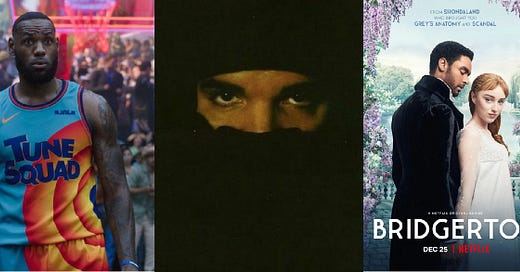

The point of this article is not that sex sells. Sure, it does, at a more-than-2.5x rate as compared to its next best competitor. 365 Days has two sequels commissioned, too. Bridgerton, Sex/Life, and tropical reality show Too Hot To Handle are in contention for this year’s top Netflix offerings, amidst an obsession with kiddie stuff. But my point is, we probably don’t understand how much data (that is we users) drive content strategy. It goes beyond the whole “Netflix shows you customized thumbnails for content” feature.

It’s funny (and extremely coincidental) I was watching Space Jam 2 now, because no matter how mid it is as a sequel, it has one ghastly prediction about our future: what if algorithms could drive content strategy? And I don’t just mean feeding images to neural networks, or creating deepfake voices out of things that were never said by the people who apparently say them. I mean a full-stack solution to making movies — you receive consumption data, associate that with scenes most likely to become popular, and you use that to make your own movie. A few years ago, there was a sci-fi film called Sunspring, starring Thomas Middleditch. The script was a product of AI — an NYU professor fed a neural network screenplays from 80s and 90s sci-fi. Now imagine you fed scripts of the top 20 Netflix movies to a similarly-built system. The screenplay could be really messy, and possibly the most esoteric, divisive piece of arthouse ever. But it’d be worth seeing what the lines are like. How about who are the actors in it?

I’m not going to be debating the merits and demerits of having AI run media consumption, especially when it comes to originality. There’s enough to unpack its implications, so I’ll leave the discourse for you. A better yet idea is to see if an AI can replicate a film producer’s timeline — May-August is for summer blockbusters, November-January is for award-winning films, everything else is for some trashy stuff. The question (one that Space Jam 2 poses in a way) then seems to be — how profitable would this AI be vis-a-vis a production company? I’m acutely aware that showbiz doesn’t work that way at all, but consider this: terms like Oscar-bait, indie, arthouse etc indicate to an extent that you appease certain sections of your audience at certain times. There are times to earn “indie cred”, and times to earn serious cash over anything else. Imagine AI taking over casting decisions. By that logic, in 2013–14, I would have seen Matthew McConaughey almost everywhere. Or Donald Glover everywhere if it came down to 2019–20.

It’s also worth thinking that Martin Scorsese had a problem with this set process. His argument was essentially that the Disney-Marvel model doesn’t allow for originality in thinking. The movies themselves may be great, but they all follow a set template (an argument I now disagree with, but he isn’t wholly wrong). Take sex again. MXPlayer has become a solid competitor in the Indian market on the back of erotica. It’s the top SVoD service in India when it comes to time spent per user (7.8 hours/month). ALTBalaji is very open about the popularity of their more explicit content, too. It’s easy to say this now, because in a pandemic, you don’t have a viable substitute to erotica that is not porn. Until things subside, vicarious living is your best chance at both entertainment and base pleasure fulfilment. It is also not a huge coincidence that Prime Video dominates Indian stand-up content (and South Indian movies). Given the complaints we have today over how template-y, privileged Indian stand-up is, answer this: do you think you could write skits the way they do if you watch all their videos? Of course you think you could, regardless of whether you actually turn out successful.

Rick Perlinger writes for WIRED how AI and NFTs are unsettling history. He lays down a simple concept: a lot of people could sell copies of the Zapruder film on a blockchain by claiming to be original footage of JFK’s assassination. More simply, people uploading the same viral video on YouTube under their own accounts. He sums it up with this superb line, inspired from one of the most expansive books I’ve ever read:

“The quagmire recalls Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, where American craftspeople build near-perfect counterfeits of American cultural collectibles. Authenticity is based on aura, aura on belief.”

In the information age, it’s easy to sell a template as something original. We have short memories, and it takes a while for most of us to see trends. Unless the people calling for change is an organized critical mass, who decides how content gets created? If nothing else, you may now have an answer to why Netflix has these dips in their content quality. If there’s more users who need spice, that’s where the money is going. Tl;dr — it’s largely us driving content quality.

Yes, at numerous points I’ve wondered whether what I’m saying makes sense. But my research about related ideas surprised me as to the extent of automation in business and media. I was immediately thinking of content marketing because I wrote “content” so much here, and a search didn’t land me too far. Here’s a Hacker Noon article outlining the extent of AI’s impact on the field. Fair warning: it goes beyond scheduling posts and tracking key performance metrics.

I do intend to write more, which is why there’s a part II. That will cover what I think will truly solidify my thoughts, and it has a lot to do with a music streaming app that’s best known for its logo’s similarity with that of Good Day biscuits. Also my favorite morning combination, with a cup of tea.

Until next time.

(As always, all underlines contain the source links.)