Hi folks :)

I’ve wanted to write a hip-hop piece for a really long time. I’m sure it must be pretty evident from the song choices I use on my pieces otherwise. But I’ve always known that I wanted to write a sprawling tale that fused where I have spent most of my core memories in the last 4 years, and my favorite genre.

Then I became a fan of Delhi hip-hop, and a piece came together for me. I knew I wanted a few more reads under my belt before I undertake something this ambitious. This two-part piece would be nothing without the people I’ve interviewed.

My pieces are natural extensions of the questions I have in my brain. If I can’t find satisfactory answers to them online, I see if I can answer them for myself through this newsletter. This also falls in that bracket, except it’s more personal than any other deep dive I’ve ever written. I’m so glad that I will be ending/starting this year with this duology.

On that note, this is a playlist that I would request you to play while reading. This is all from the desi hip-hop stable, predominantly from the Delhi-NCR scene. Many of these songs are relevant to the piece as you gradually read it. If Hindi is not your first language, I’ve added reference numbers that link to a document of translations :)

This is Part 1 of Return To Home Bass. Part 2 will feature some more people beyond the names you see here, and will also be a little personal like this one. Happy reading!

Metro rides can reveal a lot about you and where you live.

As someone who has to live in and work out of Gurgaon, I travel to Delhi quite often. My weekends squarely land me in its most value-for-money lip-smacking eateries that I know I won’t find in Gurgaon. And it’s not necessarily just the most bougie areas of the city — there’s a sub-conscious attempt to make a comforting haunt out of every nook and corner I instantly like.

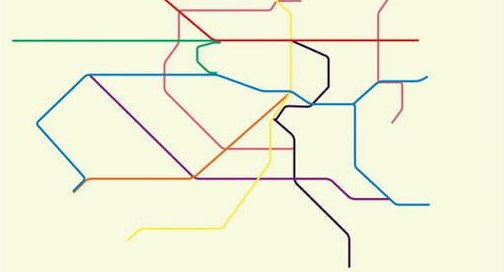

But every time I have to head back home, the route is the same. The Delhi Metro’s Yellow Line is the beating heart of the entire train system (sorry, blue liners) — longest, last to shut, the most crowded. The south-most 8 stations of the line mark the bridge portal between Delhi and Gurgaon. Traffic lights and car beams turn into large, empty farmhouses and open-air banquet venues on your way back. Then houses slowly start populating. Then come the massive glass buildings far in the backdrop, the structures most symbolic of Gurgaon — if they have anything to say at all.

On 26th November, a cold Delhi Saturday, I returned from INA in a metro cabin after meeting a friend for a lovely lunch. An early winter sunset illuminated the cabin I was in, but then I saw those huge, ugly, round bastions of capitalism they collectively call CyberCity. Most rides like this are accompanied by harsh, industrial, abrasive music, in tune with the pace of Gurgaon life. The lyrics fit perfectly with the instrumental — flexes of grind, classic slang, threats of violence against enemies and fakes, slick wordplay, and an unsaid belief that the artists know they’re absolutely murdering the beat. “PEW PEW” is one such track.

And you know what? I reveled in it. For 2 minutes and 21 seconds, I had enemies I didn’t name, jewelry I didn’t own, a chip on my shoulder, and a challenge for the PCR van to catch me. Considering who raps these lyrics, I Rawal-ed in it:

“Talk to the hand mere haath mei hai dhan,

Mujhe pta hun mai bhundfaad chaat meri kam,

30 laakh stream 4 mahino mei album pe pehli,

Promotion pe paise nai talent hai baby” (1)

Daytime Gurgaon is a struggle, despite its streaky crimson sunsets. You’ve seen Los Santos from GTA V (not San Andreas), right? Gurgaon feels like that, minus the Hollywood sensibilities. Where GTA satirizes the American Dream, Gurgaon feels like a Pyrrhic victory for the Indian parallel. You hear a friend talking about his time at Los Angeles and its recklessness and you say to yourself, “This sounds like Gurgaon.”

Different people have different coping mechanisms when it comes to surviving the pace of the city, and keeping sane. Mine is listening to hard-hitting, gym-bro, kill-em-all hip-hop while strutting corporate corridors. There is a (flawed) sense that unlike the legacy areas of Delhi dominated by generational wealth, Gurgaon is meritocratic and deserves its riches. That its large professional base is all shop, little talk. Letting the talent and the real estate portfolio scream the loudest.

But the thing about “PEW PEW” is that it comes from Delhi-based artists, one of who went to the same university as me. You could listen to all the Kendrick Lamar and Future and Missy Elliott to feel hype. Yet nothing feels as close and relatable to when the beat has the soul of the region you live in. For the cut-throat, money-minded, seemingly meritocratic, haphazardly-designed maze Gurgaon is — the menacing bass, the venomous spew, everything fell into place. You have little choice but to embrace it for survival, and somehow feel gaslit into seeing the good in the city.

Stockholm Syndrome, if you will.

“Yeh sheher nahi, mehfil hai.”

Most people would argue that in 2022, for Delhi and the National Capital Region, only the first half of the sentence above is true. Especially after 2014.

The idea of romancing a potential love interest in Delhi - or Delhi as the love interest itself - has for long been a fantasy perpetuated by Bollywood. The narrow lanes of Chandni Chowk, the sensory overload of Jama Masjid, the cutesy spots of Sunder Nursery, the green vastness of Lodhi Gardens, the hoity-toity brown-colored civil buildings of Raisina Hill. Somewhere in 2009, AR Rahman said that it might be a hit formula to make an album that’s a combination of some of these utopian concepts.

Don’t get me wrong — I love Bollywood songs about Delhi. There’s something about watching the gang from Rang De Basanti drive that car of theirs around India Gate. Or watching Sonam Kapoor overlooking the old-world charm of the Delhi-6 area. Or getting a teaser to the eventual real-life romance between Saif Ali Khan and Kareena Kapoor Khan with the Humayun Tomb in the backdrop in Kurbaan.

But Delhi is also — and has always been — about the confrontational East Delhi, the loudness of West Delhi, the bratty opulence of Mehrauli’s clubs and the slums that surround them, the smog, the road ragers, the terrible first dates, the loneliness that exists in the artificial architecture that crowds Delhi’s borders; the underlying current that there is, and has been, something fucked up with the city. And if you believe that a city is its people, then Delhi has negative karma. It’s a weird disconnect to have some of the most mellifluous music known to India be about a city that is struggling on every possible human front you can count. Climate change, politics, infrastructure, transport, family — you name the issue, chances are Delhi is in some limbo phase of it.

Of course, there are movies and songs that bridged this disconnect. Khosla Ka Ghosla released in 2006, and we saw an accurate depiction of what people of the city might been like — specifically, middle-class West Delhi uncles and villainous brokers. My own all-time #1 Delhi depiction — Dev.D — came out in 2009. It was a saga of blurring in and blacking out at different parts of the city, masked as a story about the intersection of a crisis of masculinity and romantic obsession. Delhi Belly felt like a representation of life as a 20-something male bachelor working in the city. Titli resembled some of the blunter nature of people, friends, brokers I knew.

(Yes, Delhi brokers are disgustingly natural grifters. Slicker than BYJU’s sales teams.)

Music-wise, though? All of these movies had bangers that reflected Delhi in one way or another. “Pardesi” from Dev.D has a trance for a music video that takes place a in a shady garage bar in the dark locality of Paharganj. Oye Lucky Lucky Oye’s music is the equivalent of a cheerful escapism, hopping from one neighborhood of the city to another. "Dilli Dilli” has a frenetic pace that foretold the kind of movie No One Killed Jessica would turn out to be (and more):

Mori jaan pe japti banke, banke kaali billi

Japti kaat kaleja le gayi, mui Dilli le gayi (2)

Not a lot of this music felt like it came from a lived experience. Naturally, the nature of Bollywood music production is fairly composer-reliant. Names like Amit Trivedi (who has produced a lot of the music above), Ram Sampath, AR Rahman are all brilliant, of course. But they’re bound by the visual media they accompany. There’s something about them that, to me, doesn’t scream, “Maybe this music was made from the kind of dingy rentals one may inhabit in the city, 3 blocks from my own street.”

Now? Indian producers are turning Bollywood samples on their own vinyl heads — much like Jeenedo by Udbhav on this playlist. Famous rappers/producers often have a type-beat associated with them, that other budding producers try and copy to get their attention — this is a DIVINE type-beat. Dudes no more than 23-24 years of age are busy minting money crafting a future where their type-beat hopefully goes global. Rappers are switching flows the same way you imagine Goku charging up his ki to achieve super-saiyan status. And they live here, come from the areas that we refer to colloquially. Old songs from the 70s are looping and opening into head-scratching quick-tempo instrumentals that could background score that memory of the first time that you, as an outsider, landed in Delhi. And that could go either way — if you were wowed, perplexed, or horrified by what you saw. I’ve had multiple moments in Delhi where I’ve experienced all three simultaneously.

“Kismat ki chaandi hai pighli pighli

Dikhti shakal apni dhundhli dhundhli” (3)

Music Makes You Lose Control

Nayi Dilli mai swagat hai, aadat hai bangayi

Jab se baarvi mai phukte the hum (4)

The first few signs of a Delhi hip-hop movement came from b-boy break dancing. Gabriel Dattatreyan, an assistant professor at the Department of Anthropology at NYU, recalls to me the days of yore in the city when he was researching Delhi’s burgeoning scene for his doctorate thesis on the global familiarity of hip-hop. Punjabi mainstream music had taken off — owing primarily to the unicorn nature of Honey Singh. And Yo Yo (among other similar popular ilk) was often the subject of mockery and insults by Delhi’s then-up-and-coming hard-hitters, who have presently crossed multiple strata of fame — Raftaar, Ikka, KR$NA. They would pride themselves on their West Coast gangsta inflections with a North Indian finesse.

And then the b-boys started trying their hands at writing bars. These were primarily heterosexual men who had come to the capital in search of a new, dreamier, more fulfilling life. Gabriel’s book begins with the picture of a migrant late teen who would draw graffiti, improve his pen game, voice his story in the numerous public spaces of the city — much of it as a respite from the dreariness of earning bread like millions of people do every day in India. They got more exposure to pop culture and consumerism than anyone in their family ever had before them.

There were two major levers that allowed this democratization. One was, of course, the internet — even in its disgustingly glitchy pre-Jio 3G form. But second, which is more relevant to Delhi, is the existence of the metro. The Delhi Metro is one of the most successful large-scale public transport systems in India, to-date. It takes 1.5 hours to go from Gurgaon to Connaught Place by metro. You could possibly cover all four cardinal directions of the city in a little more than half a day, and feel like you’ve seen 6 different regions. Couple that with the prevalence of rap cyphers happening across the city — most notable being the MC Kode-hosted Spitdope, that sees (and has birthed) the who’s who of the scene.

Between Karol Bagh’s Punjabi liveliness, Chandni Chowk’s rusty lanes, and Ghaziabad’s wild infamy, Delhi hip-hop was poised to be a grand, tasty stew of perspectives that wasn’t just about the romanticization of its monuments. This has also led to the formation of diverse collectives, most of who may not even be Delhi natives. Metro rides can indeed reveal a lot.

“Shanivar ravivar saare yaar mere saath

Maine gyarvi naap diya pura Ghaziabad” (5)

And this is considerably different from Mumbai hip-hop, where a lot of the music comes from its slums. Despite the local, connectivity between neighborhoods is fairly inconvenient in Mumbai. Even if it wasn’t, the cost of living and the lack of truly public spaces is enough to dissuade the underprivileged from going outside. Gabriel explained this to me as Mumbai’s slums being a container for artistic expression — what he believes Delhi successfully prevented. And the second largest slum in Asia is also Mumbai hip-hop’s beating heart. Because of how the metro democratized movement within the city, budding spitfires they would seldom feel the need to say they’re from the hood as a form of validation.

This marks one of Delhi rap’s most unique differentiators is how there is a distinct middle-class tone to it. Most of India’s population belongs to the low-to-middle income category. The Indian middle class is in the trenches compared to that in more developed nations. There is certainly a dream to afford everything for oneself and their near and dear ones as an artist. For Delhi hip-hop, that often comes from a place of being directionless, as opposed to being in utter dire straits.

Delhi rap feels aspirational, nostalgic, yet on the verge of going back to some unwanted old habits. Imagine the lanes of an old public housing colony, where the kids play cricket in the evening, go to tuition right after, are wowed by what a marvel GTA San Andreas (or battle royale, in a 2020s context) could be, discover Eminem for the first time, peep a little DBZ in the night, and would compare Beyblades and cricket bats. There’s a lot of innocence and camaraderie in this portrait, but Delhi rappers are also concerned with how those kids — their old pals — panned out as maturing humans. And how they survived, if they did.

The dark places that the scene’s artists tend to talk about are more emotional than physical manifestations. Overworked-and-underpaid fathers taking out their frustrations on the women and children in his household. There is little respite, yet there is an acceptance that they wouldn’t be who they are without these experiences. Here’s Ikka — who actually hails from the infamous Burari — narrating a story he has seen up close personally (if it’s not his own), from his second album Nishu:

“Mintu ki Sega me Sonic chale, Swat Kats 4:30 baje

Rank 1 mere patte bade, Bachpan se jeete na clash kare

Baap sharabi, beta awaara, sabki nazro mein mai awwal nakara

Tuition ke teacher ko office ka gussa, birthday pe mere phatte se maara”

Main bachpan se pisa bachpan se gussa bhara

Aise halaaton mein suna tha Shady, inspired hua main rapper bana” (6)

Hip-hop derives quite a bit from personal trauma. Be it 2Pac talking about his dad, Eminem calling his mother all sorts of names, or Megan Thee Stallion using angry music to recover from a shooting. Delhi hip-hop is not very different, or at least it has begun to move towards vulnerability of late. There’s also an attempt to embed such experiences within Delhi’s cultural zeitgeist. Dev-D uses the almost-mythical DPS RK Puram MMS Scandal as a plot point. Similarly, Seedhe Maut’s Anaadi culminates a dysfunctional father-son relationship into the kind of regular road rage death that turns into a Delhi newspaper headline.

Stagnant Water

Delhi’s cultural zeitgeist is a little difficult to break down. The city has lore no matter where you look. Some of it is also very uncomfortable conversation now crafted into Netflix IP like Delhi Crime, but this piece isn’t about that.

What makes Delhi’s canvas so all-encompassing is a) its various areas, and b) its people. The fact that every area has a different identity, as well as distinguishable, desirable and unwanted identifiers adds to the love-hate that its people experience.

Jayant Bakshi is a social sciences graduate from Ambedkar University. But when he tells someone that he’s from East Delhi, all his prior qualifications take a backseat. It doesn’t matter where he studied — he’s already generalized. Beyond that, nobody cares that he’s from Anand Vihar — a civil upper/middle-class residency in the grand scheme of East Delhi’s impoverishment.

“Stagnant water”, he calls it. In fact, what Jayant feels about how he is perceived, even as someone well-off in otherwise a poor region, is pretty aptly reflected in this satirical Outlook piece from 2019, titled “Where The Hell Is Seelampur”. East Delhi is no stranger to ghetto-ization. And Jayant is theorizing to me why the eastern sides of so many cities across the world are ugly — maybe something to do with rivers flowing eastward? Unlike a Saket or Chhatarpur in the south, East Delhi is used as an umbrella term for its individual areas. Frustrated, moody, grimy — Jamunapaar looks like the city planning manifestation of an insecurity.

And the insecurity is pretty big. This lovely short piece from Down To Earth talks about two Delhis: a South Delhi, and Delhi’s slum colonies (like in the East) that were built out of a need to house migrants. It explains a bit of where the insecurity stems from. But that’s only one way of dividing Delhi into two.

South Delhi’s money is multi-generational — you’ve heard the jokes about South Delhi kids. East Delhi, however, has primarily nouveau-riche residents. They earned their riches through scrapping and buying land for cheap. Real estate is a massive status symbol in Delhi-NCR first, long-term investment next. Yet, Jayant tells me that in an attempt to play the status game, East Delhi residents are perceived as gaudy to the rest of the city. Signals like buying branded jerseys instead of first copies and knockoffs — a culture that Delhi markets like Palika Bazar have popularized — become important and aspirational. A culture that has intersected with Delhi hip-hop.

East Delhi is also incredibly polarized, both in terms of wealth and politics. Even among the economically disadvantaged of Delhi, those in East and North-East Delhi have had it worse. In the 2020 assembly polls of Delhi, The Quint reported that much of the communal violence up to the voting happened in east and north-east Delhi. East Delhi is a BJP bastion. It’s not enough that random fights happen here all the time anyway.

Jayant says that he could once see the Sun hide itself — that’s how smoggy and grey Jamunapaar can be. It’s appalling how common a mugging in Anand Vihar is — Jayant recalls a time where his phone was stolen at knifepoint, and the police did zilch to recover it. How he’s lived here, even as someone with financial privilege, is reflected in these bars from another Jamunapaar resident, rapper Raga:

“Jamnapaar ka safar tu

Kar tu paar aaj

Mere sath aaj mere yaar aas-paas khaas-khaas saare badmizaaj” (7)

Jamunapaar became a hub for rap cyphers a few years ago. Raga was born from rap battles in the region, and in 2022, he signed on to American label Def Jam’s Indian division. East Delhi underground cyphers then seem like a respite, eventually only to turn into a legitimate career option. An escape from areas like Dilshad Garden, Karkarduma, or jhuggi jhopri clusters like Kalyanpuri and Khichdipur.

Away from the physicality and emotional strife of Jamunapaar.

Bhature Western

On the other end of the Delhi Metro Blue Line, bang opposite Anand Vihar/Yamuna Bank station, is the vibrant West Delhi. The image of being the land of some of the best chole bhature in the country certainly helps. Having an alumnus like Virat Kohli is icing on the cake.

Bharg Kale appears on my Zoom interface, sitting in a room with the most vibe-y purple lighting. After all, you can’t be known for cooking monster beats like “PEW PEW” and NOT have the room where you make music all spiced up. Among other things that will feature later in this story, he tells me that one of my favorite songs of 2022 — West Delhi anthem Kaloli, which he produced — was initially meant to be a type-beat.

The cover for Kaloli is that of the famous, Virat Kohli-endorsed Rama Chole Bhature. The song is about a West Delhi colony, where the kids wear narrow pants to school, buy (yet again) first-copy Jordans, drink in gleeful abandon, are as happy-go-lucky as one gets. Delhi is home to a lot of fashionable number plates — the kind where 8055 is designed to look like BOSS, and 4141 like “पापा” (meaning father in Hindi). The scooty having “fuck you” written behind is almost believable. West Delhi is loud and proud, peppered with small parks smack dab in the middle of public housing.

“Scootiyan di number platan te likheya fuck you

Dikkiyan ch paiyan wooferan di crate boom boom

Boom vajda ae poora jail road

Tihar vich nachde ne kaidiyan naal jailor” (8)

Abhiroop Dey is an engineering graduate who works for a management consulting firm. Currently a Palam resident who finds himself in Gurgaon quite often for work, his experience of (south) West Delhi is partly what you’d expect from a song like Kaloli. “Your colony friends are your first friends”, he says. There’s an unsaid brotherhood that exists with them, that celebrates alongside you, that stays with you even after everyone goes their separate ways. A very Punjabi way of living.

But these colonies tend to be very homogenous, too. Upper/middle-class West Delhi is a lot of family businesses. Kids who haven’t had the social privilege to explore alternative careers follow the father’s footsteps as a means to an end they don’t know yet. Chhavi Bahmba, a visual designer and longtime Hari Nagar resident, talks about how she knows so many friends who have struggled with their individuality. A running joke she has with her mother is how they didn’t know life beyond a 5 km radius, beyond the same 4 friends from school. She was/is surrounded by Kapoors, Khannas, Aroras, Marwadis, Agarwals. For the Delhi hip-hop fan in Chhavi (she has a brilliant Delhi hip-hop Instagram page here), the lyrics speak to her.

In West Delhi, families laden with money — ideally from businesses and rent receipts — are also fearful of when it may leave. This results in a lot of frugal practices. However, when it does happen, status signaling among them also ends up being perceived as gaudy, simply because it’s more material than subtle. Much of the younger generation’s idea of status and individuality ends up being warped — especially when their families (and the colony aunties) already have a defined idea for their future. And a lot of the music from the area does lament about the need to be remembered and not be forgotten in their parents’ dreams for them.

How do the kids of West Delhi deal with the fact that this is true for so many of them? Bakchodi. Gossip. Random fun. Bitching. Saying wild, weird things for jokes. The kind that you would hear in Kaloli. It’s their version of using humor to cope with trauma. Even often at the expense of being politically incorrect, since cancel culture is the last thing on their minds. All that, and the age-old escapist activity of drinking:

“Velle bande badmash eh colony de” (9)

And West Delhi hip-hop seems in complete contrast to this gaudiness, this unsaid caging. They’re trying to define cool on their own. They’re trying to move away from the flashy cars that can often be seen on their main roads.

The lanes of Rajouri Garden and Karol Bagh are occupied by families who settled here after the Partition. Maybe, the sense of community comes from the fact that these families have seen conflict across decades.

The potential reparations that are owed to community members (for example, those who were victims of the ‘84 violence against Sikhs across Delhi) now are vote bank fodder. Areas like Tilak Nagar are instead crumbling under the weight of failing infrastructure and drugs.

This is the zone where Prabh Deep operates. His breakout debut album, Class-Sikh, was self-admittedly unabashedly a Delhi-18 talk show. He has a chip on his shoulder especially when it comes to state neglect of his people, freedom of speech, drug abuse and school. Even when he disparages what has happened to his streets, he can never shed where he comes from, never not be full of life, never not be bakchod:

“Kara fun preshaniya da kadda hal

Fikar ni mai krda hona ki mere naal kal

Te hoya ki si kal oh vi yaad nahio mainu

Zindagi aa jeeni aaj bas yaad aio mainu” (10)

Gabriel tells me of the time he met a 16 y/o Prabh Deep, who was introduced to the power of storytelling through rap through b-boy culture that Gabriel was studying at the time. Here’s a CRED ad where he talks about what being a Rs 3K/month clothes salesman taught him.

East, West, and the northern migrant settlements of Delhi pale in comparison to how much the cultural heritage (owing to monuments, of course) of South Delhi is in constant conversation. Chhavi says that this high ground of Mehrauli’s cultural heritage is what adds to the class struggle between the old rich and the new rich — that the latter are always trying to prove their status. Where the old rich live is always in vogue, owing to the aforementioned romanticization.

But some people like AB17 don’t care. Further south-west is the Najafgarh area, notorious for crime. That’s the area he has to inhabit and embrace, even as he wants to get away from the gangs of thugs who rule his locality. But his trap-inspired, drug-induced music is how he chooses to be king of the hill they call Delhi-71:

“Baarvi marksheet ni lagi hui charge sheet” (11)

Rap is no more just lyrical miracles on a boom-bap beat. Artists like AB17 are stretching the barriers of what is possible when your instrumental sells the image of a shady smoking room — the hallmark activity of society escapism. The substances go beyond your usual Gold Flake, marijuana, or scotch. You need a trip to speak about the tunnel vision that has clouded your lived experiences. While often derogatorily associated with “mumble”, Delhi hip-hop is also very much this, too.

No Hook

Much like its lore, Delhi’s sound is also hard to pinpoint, beyond a certain black fog that hovers over it. When Leonard Cohen sang “the minor fall, the major lift”, he was probably talking about why so much of Delhi hip-hop plays on some minor scale on the musical octave. It makes you an oft-unwilling slave to the (city’s) rhythm.

Chandigarh-based producer Viraj Gulati, who goes by idek, says that Delhi hip-hop has a lot more 808s — harder bass kicks, snares, and hi-hats. He spent a lot of nights in Delhi, primarily to market his music — and to him, the city’s music feels a lot like its uncertain, foggy nights. Despite being from Chandigarh, he believes Delhi music has more balls of steel. Delhi’s sound is arrogant, he says, much like its people, and is more emblematic of its nights than days. For the 20 year-old whose breakout came when he produced Prabh Deep’s Taqat from his bedroom, working overnight is not foreign. Neither is opening live for Prabh Deep.

In fact, there is literally a song called “Delhi Nightz”, by Tarun and Lil Kabeer. The music video pretty much feels like an intimidating, melancholic night in the city, even when there’s no immediate threat in the surrounding:

“Delhi ki raatein

Jahan pe kaale dhande chalte din dahade

Jahan pe baithi cheele tujhpe aankh adake” (12)

The funniest part of Delhi’s music is certainly the crowd that comes to a concert, to consume entertainment far removed from their reality. Delhi crowds can be extremely rude — they will call for the headliner while the opener is performing. Viraj’s take? “As openers, our job is to fill time. Cool changes every 6 months in Gurgaon.” It’s his version of “the consumer is king”.

Much of the credit for crafting Delhi’s sound goes to arguably India’s greatest hip-hop producer to-date, Sez On The Beat. Even idek remembers when he auditioned for a beat-making competition by Sez and Delhi-based Rebel 7, called Rebolution. Sez has inspired revolutionary desi beat-makers like Lambo Drive, idek, 3bhk, Karan Kanchan, Udbhav and Bharg. Sez is all over this playlist, if his influence isn’t evident already. But all of these producers are now expanding on their unique sounds.

For Rohini (and sometimes Pitampura) rep Karun, Hindustani classical is a go-to. He’s a massive fan of stringed instruments, and that goes beyond the electric guitar as is so prevalent in his 2022 release Qabool Hai. Sitar, sarangi, tanpura — his Mendus-produced banger Sheeshmahal is a glorious exercise in adding headbanging bass to homegrown instruments. It goes without saying that Karun also wants to make commercial bhajans — not just because he feels close to God, but also because he knows how incredible it can sound. The love for Indian music also guides a lot of production choices for Karun, like old Bollywood samples — especially since his partner-in-crime producer Udbhav is a massive RD Burman fan. The problem lies in sample clearance — until now, they haven’t had the money to pay for these samples, and they certainly do not want to get into a copyright lawsuit.

Even for the inherent poet in Karun, hip-hop goes beyond rap and poetry — he sincerely believes there are differences between the two, and words mean nothing without the music. It’s probably this philosophy that put the sheesh in Sheeshmahal when I first listened to it.

As an Air Force kid, Bharg has toured across Delhi-NCR in terms of residency. His belief in hip-hop as an umbrella term for a certain kind of music mirrors that of Karun — he wants to bridge the gap between rap and indie. He doesn’t think that Delhi’s artists set out with the explicit intention to make an entire body of work dark. What he does agree with is the idea that darkness is embedded in the subconscious of Delhi’s flamethrowers.

Bharg’s breakout album was with rapper Rawal, the much-heralded pop/rap joint Sab Chahiye. There is always a dichotomy that exists between rapper and producer which gets resolved by chemistry between them — the kind Rawal and Bharg have on the tape. They didn’t need to spell out what they were thinking. This chemistry has an entire city screaming “Dilli ka ladka par peeta mai Bombay Sapphire”.

Even as Delhi hip-hop grows more experimental over time (like with Karun and Bharg), adding lavish electric guitar outros, beat or rhythm switches, and sitars and dhol, it somehow maintains an ominous mist.

And this ominous nature of the music may still be more conscious for the firemen in the booth, who have voice the words. Like the ones who rant about Delhi’s love-hate trait. Seedhe Maut’s Rajdhani is an angry ode to the city that gave the duo everything, yet always found a way to make them beg, and make them bloodthirsty. Being the capital of India means that a Delhi hip-hop song is incomplete without talking about its politics. Public institutions like Delhi University, Jamia Milia Islamia, JNU are victims of an overarching right-wing saffronwash that calls anyone with an anti-establishment bent a terrorist. Rap is aggressive poetry about politics. And rappers understand it more than anybody. And Seedhe Maut’s Rajdhani is no different.

“Rajdhani rajdhani, 100 sawal hai lekin terpe hai ek bhi jawab ni

Paida hua tujhse zindagi tujhme bita di

Seekha jo bhi seekha hai tujhse

Toh hun tere jitna khoonkhaar bhi” (13)

It’s years of frustration that comes through as telling a lived experience as it happened. Years of not feeling represented when someone discusses Delhi as a fantasy, a place to be.

I always thought that the idea of studying and possibly residing in Delhi was lovely. Only much later did I realize that my idea of the city is by virtue of Edwin Lutyens’ propaganda. Rent there is very high, and it’s the bastion of the legacy elite. I would hear and make jokes about how Rohini isn’t really a part of Delhi because it feels so devoid of the mainstream idea of Delhi’s bustle that was sold to me. Only to realize much later how mistaken I was.

If we were to go by all this music, it sounds like Delhi’s natives and migrants both are wrestling with a massive tussle between their love for their home, and when their home kicked them in the shins. I probably experience only 10% of all this by virtue of privilege, but even that feels overwhelming. This love-hate is punctuated by one’s class, caste, and gender. It gets worse if you’re a woman, or if you don’t belong to the most elite. But somehow, most people feels it on some level. Probably because no one in Delhi is truly a Delhiite — they all come from different parts of India.

Long metro rides make you wonder where so many people are headed, and why they are perpetually forlorn. These are people who travel all the way to workplaces in Gurgaon and Noida, from the Delhi that pop culture doesn’t want to talk about. The idea of a routine like that is infectious in its sadness. You wonder if romance of any kind is possible in a place like this, when the city occupies so much of your mindspace. The kind of romance and cuddle weather that we read about on social media when winter here sets in.

And when a longtime resident like Jayant says that he might just end up coming back to where he’s from, you wonder whether this is really Stockholm Syndrome. The highest form of gaslighting, that’s so subtle that you never see it coming. Like a huge cage that you feel like could never get out of, but you’re not sure you want to. His family never did, even when they were faced with the choice multiple times.

When friends of mine would say how much they would want to get away from Delhi, I’d ask why. When Twitter has its monthly “my tier-I city is better” battle, I conveniently forget the times the city has been unkind to me, in all its greyness, in the people I had to deal with, in the culture shocks it has given me, in all the times when I couldn’t relate or adapt.

But sometimes, I wonder if it’s all worth it. When there’s no one I can identify with on those packed metro cabins, the loneliness rides over me. And I don't ask why.

“Bhar lu majburi kar lu crush yu

Kush fuku bharpur tang hu mat puch

Sang tu nahi ghar dur, sard yu sab kyu” (14)

I just play the music and take it all in.

Part II comes out January 1st week, ideally to kickstart 2023! I promise Part II is brighter than this, features some more people (including the ones who were here), is definitely more fun!

Obviously, thanks to: Bharg Kale [who’s cooked up another one recently, here], Viraj Gulati [who’s about to release soon as Smitt in Smitt and Wessn which is on this playlist], Gabriel Dattatreyan [whose book is here], and Karun [who just received a massive endorsement from Honey Singh, who apparently certified Karun as a lover boy — more on this in Part 2 :))]!

Special thanks to: Rijul Seth, Ishartek Pabla, Ritika Varshney, Meher Sachdeva, Tanya Singh, Dhruv Trehan, Aditi Singh, Abhiroop Dey, Nicaia D'Souza, Jayant Bakshi, the kind fellow Substack-er

, Manik Dua, Taran Kaur, Chhavi Bahmba! All of these wonderful folks have helped me so much across both parts — landing facetime with artists, giving me their thoughts as Delhiites, all of it. The totality of RTHB wouldn’t have worked without them.Also, the best beta testers ever: Shruti Gupta, Kushan Patel, Jayesha Koushik, Molina Singh, Sunaina Bose!

And for a bit of help on the translation!

Until next time, and till then, Happy New Year :)

Really interesting and fun read. Great descriptions of all the places. Thanks for the music recommendations

Looking forward to Part 2! Keep em coming!!