Hi! You can certainly read this without reading Return To Home Bass 1, but I would highly recommend checking that out first. The story of Delhi and its hip-hop is much tighter that way. You know, much like Gangs of Wasseypur I and II. My 5-hour magnum opus or whatever.

Jokes aside, you should read 1 and 2 both. You can go to RTHB 1 from here:

All non-English lyrics have reference numbers that lead you to a Google doc with the respective translations. I hope you have a great time reading this and listening to the playlist. If nothing else, I can promise that the playlist is brilliant — it’s one heck of a home run in my humble opinion. If someone from Spotify India / Gaana / Wynk / JioSaavn / Apple Music India / YouTube is reading this — I know it’s a bad time, but please hire me, pretty please.

Happy reading!

It takes a while for Delhi-NCR residents to understand that surviving the city is basically just a series of “me and the homies” memes. This could not be truer for hip-hop collective J Block.

I meet Waris and Saqlen near the Qutab Minar metro station, and I walk with them to the destination. He’s 21, and he just made a poppy song called Frootie, along with J Block co-members Faizan and dr chaand. Saqlen is J Block’s manager. It’s a lazy weekend for 6 of the 13 members present, living close to the metro station. Besides two people, all of the rest present at the time do not originally hail from Delhi.

At the time, J Block was looking for people to handle social media and operations for them. 2022 was a record year for them — over 1L listeners and 4L streams. As I enter, I’m greeted by Faizan and Lonekat, and Morocco were playing Portugal in the World Cup quarterfinal. Nobody, absolutely nobody, wanted Portugal to win. “Fucking colonizers.” I enter their studio, which is where we have our conversation. Later, I meet (Lil) Kabeer and Adam Bo. The dining room had a bowl with cat food. But their cat, Joey, was nowhere to be seen.

For a good hour or so, Lonekat — real name Siddharth Sengupta — thought that I was there to be interviewed for a position to manage J Block’s social media. Hilariously, he had no idea why I was the one asking all the questions.

J Block was never supposed to be defined. Faizan tells me that all of them were on their own roads and knew only 1-2 of the entire current collective before. Facebook was quite the matchmaker. Waris, a multimedia student at Jamia, loves making videos, and Faizan knew him through one such project he had done for his brother. Waris knew Lonekat as the guy who, in no uncertain terms, digital-slapped the shit out of Facebook sanghis. Kabeer came into the picture through Waris.

J Block had crossed over the rap collective-to-brotherhood bridge. Together, they had seen enough shit. Like the time they tell me they had to vacate their last flat back at Kishangarh, on the morning of a gig. This, after leaving the Sarita Vihar J Block that inspired their name — that’s 2 rental changes in nearly 1.5 years. We share considerable anti-Delhi landlord/broker propaganda. With how much we discuss landlord complaints, J Block’s idea of drill music will not be the sound popularized by Pop Smoke. It’ll be the house downstairs with their construction.

All experiences that contributed to making their latest album Kho Kho. Political, sonically mesmerizing, absolutely stacked, there’s little doubt that J Block had a lot of fun making this album, and it shows. And it was made in all of 2 days — recorded, mixed, mastered. It’s also a lot of storytelling — with a song literally titled Kishangarh.

“Kismat ke bistar ko laangke

Phandon se bani ek seedi ko baandh ke

Challe ke baadal ko phaandke

Bann jaana Suraj aur ladh jaana raat se” (1)

Politics is important to them. Lonekat is the oldest, and thereby the voice of reason among the group. For the longtime DU graduate, politics is daily existence — “even if I write about sex with a partner, it’ll have politics in it.” Faizan is a graduate of JNU, Waris is a student at Jamia. None of them had music in their initial life plans. Waris loves joking about how he loves forming connections just because the other person was a Muslim like him — which is how he says he befriended Faizan. J Block also proactively check each other’s lyrics — if there’s a word that’s extremely derogatory to a certain identity (race / religion / caste), the inclusion of the same is heavily debated.

Both Delhi and hip-hop are enriched by a strong sense of community and companionship. Between asshole neighbors, shitty landlords, and feeding one cat, J Block recorded an album in 2 days. They’ve battled all the hammers that Delhi could possibly throw at them, and made bangers — not only as a collective, but for their individual tapes, too. They’re trying to expand the horizons of what is possible at the intersection of visual and audio. Delhi’s hip-hop scene blossomed into something bigger than the city because of rap cyphers, collectives like J Block, and the metro.

What The Fuck Is So Funny About Me?

J Block’s camaraderie shines through their humor. There’s no doubt they’re funny, and it’s reflective in their music. Delhi hip-hop is a lot of internal and third-party strife, but you best believe it will be dealt with, with hilarity.

During the 2 days that J Block made Kho Kho, Waris was back home in Lucknow. In our conversation, he (rightfully) whines about how he isn’t there on the album. This FOMO is why he made Frootie. Produced by Faizan and featuring dr chaand, yungwaris narrates a fun tale of what seems like a one-sided crush on a woman he wants to have the namesake drink with. Sure, I felt sad for Waris, but it’s hard not to laugh at the cheeky metaphors he uses:

“Been 2 days baby, MIA

Dil mera bhaari hai kilo 2

Tetra pak bhare gaadi mein fir

Knock knock, ab sang chalo tum” (2)

Being seen-zoned is still a first world problem. Bad drainage, water and electricity crises, terrible landlords, food poisoning, smog — Delhi’s primary coping mechanism to all of these is humor; especially the kind where you’d like to spit slang quite often. Unlike elsewhere, nobody would bat too much of an eyelid if you threw the Hindi word for “motherfucker” around (unless you want said eye blackened, you should do it outside Delhi). It’s entirely possible for someone like me to find myself not being able to stop muttering the word for the smallest nuisance, in any setting, formal or not.

While not ideal, gendered slurs have become part of the dictionary. It’s mutually understood that these words mean little except for displaying an aura of anger. The weight of either word has then been lightened to just words that are thrown around because it can feel therapeutic to scream them out loud without having to face consequences for it. It’s how the weight of the word “fuck” has reduced over time, and now you get to see it on news headlines. It’s the verbal equivalent of smoking — despite being not the best course of action, throwing slurs is the ultimate relief in this city. At least I can cry about my woes in Delhi in the crassest way possible without anyone judging me.

Here’s Garv Taneja, aka Chaar Diwari, moving like the Bounce Tales ball on a killer beat — talking about a constipated day with no water in the house….

“Paani nai aa raha, bhenchod!” (3)

….yet having the balls to say he feels wet and fresh in his drip:

“Khana khaya par na aai dhang se tatti mujhe

Tabhi toh maine gatki hai hajmola

Aur mai drip se hun geela, par lagun bhola” (4)

Of course, there’s MORE than one piece of pop culture that’s titled “Delhi se hun bhenchod”. Be it the song that’s just a display of Delhi machismo partying with pegs and momos, or the show by comedian Nishant Talwar, Delhiites have now owned the image of being armed with a barrage of foul-mouthing. Whether that image is self-generated, or reinforced by pop culture, or both, is unclear. However, it went from being a survival instinct to a mark of identity and bonding among the city’s people.

Being foulmouthed and supposedly having the contact of that one goon with a Scorpio have become staple cliches that have — both sarcastically and not — made their way into Delhi hip-hop. As with any mainstream hip-hop movement, the Delhi scene is also no stranger to having gendered slurs once every 5 lines on average, if not more.

Below is Fotty Seven explaning how he appears to be a “galat launda” (literally “cool criminal”). What is Delhi’s music is incomplete without it having some sense of (male) entitlement? And “Galat Launda” is precisely that kind of song, but with a deft touch of self-awareness. Spoiler alert, he needs money because his dad won’t give him any. So he demands the shopkeeper give him actual change instead of Eclairs:

“Paise jode aapas mein, fir botal daali kaagaz main bey

Kitni toffee dega, bhai? Baaki paise wapas de na

Bhai darta nahin apne baap se, matlab

Tera bhai darta hai bas apne baap se” (5)

Living For The City

Elements of humor, crassness, lethargy, bakchodi, flexing, and of course a bit of partying are part and parcel of Delhi hip-hop.

And these elements often sum up to give us “the Delhi song”.

The Delhi song is often the banger on an album. Slick, often grand production, quick-tempo, maybe a feature artist or two, and lots of flow changes. While certainly not as fast-paced or perennially wide awake as Mumbai, Delhi moves with its own gusto. The kind of gusto that makes you want to exit a boring party, only to roam around the streets where the orange lights haven’t yet been replaced by LED ones, ideally to find one of those late-night lip-smacking paratha spots in some narrow lane. The kind of gusto that leaves you too hammered to make the effort for a wholesome, healthy brunch and settle for a McSpicy Chicken. Javed Jaffrey, by Gair Kanooni, is that song:

“Sadkon pe chalte hum auto main

Raat ko nikalte hum Jordan main

Red light ke aage ek shortcut hai

Back on my bullshit, back on my bullshit

Sammad and Jatin, Maccy D breakfast hungover on Sundays” (6)

Saransh Batra shows up on a GMeet call at midnight wearing a lavender hoodie. Most people know him as Saar Punch, the lead artist behind the city anthem that featured heavily in Part 1, Kaloli. In his view, Delhi is certainly about that gusto and aggression. “But you can’t put the Delhi song in a box.” His biggest hit to-date is a Delhi anthem that didn’t talk about hotboxes, hangovers, afterparties, showing off, or fancy cars. For him, Delhi is also evocative of a certain idea of momos and red chutney, shawarma, weird encounters with the police, and driving in a black Santro.

Indeed, that’s what he does in his music video for one of his earliest songs, Ghar Nahin Jaara. The music video is about Saar and his friends driving in a black Santro receiving a briefcase from a dealer late at night. They open it, and a light emanates from it — akin to the mysterious Pulp Fiction briefcase. However, unlike the movie, we can see what comes out of the briefcase — a packet full of momos, and a massive bowl of red chutney. Saar has an unwavering belief in chutney making average momos feel like a trip. He also comes out in support of having mayonnaise with momos and tandoori momos — a Delhi concept that can often be very divisive.

But Delhi concept nonetheless. Much like Delhi’s shawarma that has nothing resembling hummus. Much like those disgusting mashups of two incoherent dishes like nutella golgappe that you get to see on reels. You can tell the obsession Delhiites have with the obnoxiousness of its gastronomy that it had to make it to pop culture.

Food, hangover cures, Air Jordans and Nike Cortez kicks, anime references, footballer namedrops, political jabs and crowds of people in rooms are all Delhi hip-hop staples. To no one’s surprise, much like the rest of us, Delhi rappers also grew up watching One Piece, DBZ, Naruto, and playing FIFA. “MMM” by Seedhe Maut narrates a supposed average day in the life of members Calm and Encore. One that involves playing a gig after popping a Crocin post a night of raging. These 6 lines summarize the essence of a Delhi song:

“Inn jaise parose kadhaiyo mein

Dikhti kyu jalan badhaiyo mein

Dalai Lama, Saitama jhai mein main Kai bana

Inko hu Rakhta main dairo mein

Deal karu mana dekh signed hu main

Aaj ke liye Bruce Almighty main” (7)

Taran Kaur has lived in Delhi for all of her 22 years of existence. She can’t see herself living anywhere else, because everything is so conveniently available.

Her sincere belief is that Delhi shines when you roam its streets with people — ideally on late-night car rides. She has songs that scream Delhi to her more than others — Javed Jaffrey is one of them. For her, Delhi songs aren’t just about its pace, but also how political they are. Delhi songs help her verbalize and consolidate everything she hates. For the dissident (and DU graduate) in her, these songs take her back to the CAA-NRC and Pinjra Tod protests in 2019.

The relationship between Delhi’s activists and its police couldn’t be more strained — primarily because of the latter’s lack of restraint in using force. It’s surprising how there aren’t more “fuck the police” chants in Delhi hip-hop, and many of the police references happen to be around being chased for petty crimes. But it’s safe to say that Delhi rap is little without its politics. Part of why rage in Delhi music has a grunt to it is because Delhiites have a ringside view to the slow erosion of democracy. You can avoid the news, but you can’t unsee the roads you’ve travelled by often having their names changed to something ghastly.

Or when they’re building a monstrosity around India Gate. But for Delhi hip-hop, regardless of the news, the revolution continues to be alive. Here’s Kashmiri-based Ahmer to televise it for you in his mother tongue, to a tune by Sez On The Beat:

“Aazha gasi yeti athshar

Fhandh wanaan yim aksar

Bandh karan yim daftaar

Gandh karaan yim nafar

Aaz watan saeri chuent

Asli Koshur Hip Hop, Aazha gasi laaeth” (8)

Good Time

Something that Taran highlighted to me that I didn’t realize earlier, is that — platonic, romantic, having a companion who roams Delhi with you enhances your perception of the city manifold.

Delhi has little to worry about when it comes to the abundance of open public spaces or events. Art exhibit, museum, comic book show, auto expo, gin drinking fest, food fest — Delhi certainly feels more alive when you have company in these gatherings. This is a report by the Delhi Urban Art Commission, that elaborates on the massively numerous public spaces in the city. Your experience of these spaces is heightened by the companions you visit them with.

There’s a nameless, undefined charm to how this happens in Delhi — it’s as if your companions are there as a pinch to tell you that what you’re experiencing is not a dream. You stop looking at Delhi as a big bad overwhelming place, but instead use your friends as reference points for the places you’ve been to. Friends who may even share the same aspirations as you, who looked at Delhi with the same cynicism, until they met you.

Pitampura lad, and one-quarter of Gair Kanooni, Tarun is wide awake — not just for an interview with me, but also career-wise. Fresh off his new track Mujhmein, Tarun is on a roll. He operates with a sense of grit — for which he credits his friends. His best two friends who he built a big YouTube channel with back in school, called The Teen Trolls. He wants to succeed on his own terms — he funds his own music by doing wedding shoots in Toronto and wants his friends to do well too.

He affectionately calls me beere, a brother. Beere is also the alter ego he prefers to be known by. It is the name of his most recent full-length release in 2022 — the alter ego came about incidentally because everyone started calling him that after the album. My favorite track from the album — one that reflects Tarun’s personality to me — is Eazy. While the song is about taking it eazy, the opening lyrics couldn’t be more emblematic of Tarun’s proverbial chip on the shoulder:

“Wishes bohot, beere badte reh aage

Iss zindagi mei sui chubhey, tabhi buney dhaagey,

Shayad aaj ka yeh din bada low hai,

Kal subah uth ke khidki pe koyal

Suney mera masterpiece” (9)

To Tarun, the Pitampura-Rohini area is Delhi. Beere is full of references to hotspots in the region. While he now lives in Toronto — home of the famous CN Tower, Tarun spent most of his life seeing the Pitampura TV Tower in the horizon. He remembers the fun times he had in DC Chowk — even asking his fans at gigs how many of them hailed from there. Nightly car rides — gedis — with friends in Pitampura were bread and butter. One of the skits on the album is seemingly from a gedi.

It’s on these gedis, with friends, he’s had uniquely insane Delhi experiences. He recalls when the Teen Trolls gang was driving to eat something late at night. They were stopped by a car in front of them, and a drunk man came onto them for no reason. He smashed their mirror. The stranger vehemently fought the 3 of them, who were built well enough to fend one man off. “Rukja bhosdike mera ghar hai yeh mai batata hun”, Tarun recalls saying. The man beat them up and drove off.

The 3 friends didn’t tell their parents at all. Instead, their first reaction was to go to McDonald’s. “Bhenchod usko bataunga mai”, Tarun recalls one of his friends saying later. Since they had spotted the stranger’s number plate, they were able to report and have him arrested.

Experiences like these shaped Beere. A composite of characters he’s seen and talked to in real life, Beere is a representation of someone from Pitampura. And of course the composite shares some traits with his creator, while being opposite in other ways. Beere (and Tarun in real life) has placed a firework in an Educomp machine in school. He drinks and smokes, Tarun doesn’t. Beere is self-sufficient like Tarun himself.

Above all, Beere takes it eazy. Hakuna Matata.

“Rehta main eazy, fikar nahin,

Mushkilein beeti, zikar nahin,

Kal hi raat pee thi, liquor nahin,

Zindagi seedhi, Twitter nahin” (10)

Free Lunch

“Woh sabse tez aur sabse khoobsurat

Iss roshni ki murat jiske aage jhukta hai aksar

Ek hi mez par baithe kare baatein aksar

Mera mann hichkichahat aur woh toh” (11)

Graphic designer Ritika Varshney has lived across regions in India — Kota, Bhopal, Chandigarh, parts of Gujarat, Delhi-NCR. She came to study in Delhi University. As someone who doesn’t rely on her family for financial support, and has no relatives in Delhi, she says that city’s open public spaces and hip-hop music have been saviors.

“Kuch nai hai, CP ghum lo, Jor Bagh mai chal lo”. In private establishments, there is pressure to appear and act in a certain manner. Not in public spaces, that birthed the legend of a man who made his career off of breaking into dances on the spot on some of Delhi’s most popular commercial lanes. And, of course, re-hashing the same dialogue about unemployed idiots who live in big mansions.

In fact, Puneet Superstar is one of Delhi’s most awesome symbols. I didn’t believe that the world could ever be my, or anyone’s oyster — until I saw his dancing videos. He uses the same streets that much of Delhi frequents. He doesn’t care what other people think of his antics. You could just meet him one such day, and he will greet you kindly. Delhi has mostly been kind to its street artists — clips like these sometimes go viral as well. Only recently, however, there has been a crackdown on street singers, which was also met with fury. The outer circle of CP has seen breakdancers, Hare Krishna singers, ukulele players, guitarists. Puneet Superstar is only the most unabashed version of this street art. I saw him as the chief guest at a free art exhibit at India Habitat Centre by the very-talented visual artist (and scene-maker) Sumit Roy.

Ritika hopes to catch him randomly in Delhi’s public spaces someday, dancing his heart out. The confluence of friends she can cherish, public spaces, the Dev-D soundtrack, and Delhi hip-hop has helped Ritika through financial, familial, and emotional struggles.

In fact, this confluence may often be more deliberate than you think. Delhi University is, while mostly crumbling, still the premier non-technical public university in India — both Ritika and Taran studied there. Its top colleges draw talent from various backgrounds — those extracurricular quota admissions for music and dance can be VERY competitive. Despite all its flaws, it does a better job of bringing people of various classes and upbringings to one place than most other institutions.

I hope you remember Bharg Kale from Part 1 — the next 2 songs are produced by him. He graduated from Hindu College in 2019 — 2 years my senior. Before he went to college, he had little idea of jazz. "Two of my seniors from my Western Music society took me to Piano Man to see some Ukrainian jazz musicians.” That changed his life, and consequently influences the way he makes music. He is grateful to the college crowd he met at DU for listening to Tame Impala, Hiatus Kiayote and Ella Fitzgerald for the first time ever. He credits DU’s rock band culture for his musical evolution. First opera show, first time he heard psychedelic, all because of his friends in DU.

Without these public spaces and easy access to private institutions like Piano Man, Delhi rap could not thrive as well as it has. This Red Bull mini-documentary (featuring Gabriel Dattatreyan from Part 1) on Delhi hip-hop proves just that. B-boys and budding rappers would use spots like the skate rink in Deer Park, and spots around Hauz Khas Village, for cyphers. Dance, music, graffiti, everything was open here.

Baby Don’t Hurt Me, No More

I’m not really an expert on love. Nor am I an expert on public spaces in Delhi. I (or anyone else) also have to be neither to know that Delhi’s public spaces are breeding grounds for romance. A TripAdvisor reviewer from California has an opinion on this. Even Deustche Bank has an opinion on this, but a favorable one — its Cheap Date Index ranks Delhi consistently among the most low-cost cities to have dates in.

But Saar Punch made an entire EP on love in Delhi, called Oopar Neeche. He’s an expert. The story of his second track, Maykhana, is incredulous. He was driving a then-friend (also the focus of the EP) on the Naraina flyover, back to her house in South Delhi. They were stuck in a bad jam, and on the right, there was a sunset. She asks him if he was looking at the jam on the right. He was looking at the sunset, and that was what was wrong with her — she missed the forest for the trees.

“Bas kehne ki baat nahin,

Mai kar dunga kuchh bhi tu hukum kar,

Sukoon se bharti ho kamre ki vibes

Tum gaana ho jaise koi slowed aur reverbed” (12)

For the record, not only did they get into a relationship after this exchange, but they also broke up, and Saar made 6 more songs about it. “That relationship shouldn’t have happened, man”, he chuckles. It ended with a voice note that the woman supposedly sent him after the breakup, where she made him block her. That voice note was recreated in the final track of his EP, Kuchh Bhi.

Moments like these can define simple man-made cement structures like flyovers forever for you. I know I will never look at Safdarjung Tomb again the same way because I associate it with a heartfelt moment with a person. At the same time, you could not like a pretty area because you had a terrible first date. But Delhi is a people’s city: our perception of its haunts is colored by who we went to the haunt with.

Oopar Neeche is remarkable in its vulnerability. Save for the late 2010s, global hip-hop has never been known for vulnerable lyrics among male artists. But that seems to be changing with regards to Delhi. Saar says that despite Delhi’s unforgiving nature, there is a softie within every Delhiite that can give Mumbai’s niceness a run for its money. He has his own set of friends he’s open with, who don’t necessarily overlap with his hip-hop mates. From falling in love, to a messy break-up, to coping with toxic mechanisms, to self-love, to self-destructive voice notes, Oopar Neeche is cinematic.

Tarun shares a similar view about vulnerability. “Ginke 2 dost rahe hain zindagi mai”, he says. And he shares all his highs and lows with them. A personality shield might be a necessary condition to survive the city, but significantly more important is an outlet to channel the shrapnel of emotional violence away. Heartbreak in the city feels much worse, since it mixes itself with Delhi’s classic forlornness.

It’s a tightrope walk to know when to wear armor, and when to shed it for someone else. In Delhi, it’s easy to tip over on either side of the thread. Here’s Faridabad rep, and ex-MTV Hustle contestant Agsy talking about her own experiences with being unguarded in a song about love that can destroy:

“Khaiyan to me dardi

Nhereyan nal lad di

Dar vi me chad du

Je tu banjave chan vi” (13)

Money Moves

2022 was a massive year for hip-hop in general. Many artists — most notably Kendrick Lamar — used the pandemic to introspect, and came back stronger. While the Delhi scene had some great releases in 2021, 2022 was stacked. Acclaimed releases from Seedhe Maut, Prabh Deep, Karun, Udbhav, Gair Kanooni, Sez On The Beat, Rebel 7, just to name a few. More importantly, live gigs returned in full spirit last year.

It’s hard to quantify how mainstream Delhi hip-hop has become. But, of course, there are indicators. The most recent trailer for Netflix India’s next release, Class, features KO by Prabh Deep, and All Nighter by Gair Kanooni. To date, Indian OTT releases have lacked the smart use of indie soundtracks/rappers — barring exceptions like DIVINE for Sacred Games. That seems to be changing in a big way.

More recently, the ongoing season of Bigg Boss had a special episode — a concert by MC Stan, Ikka, and Seedhe Maut. Quite possibly the largest TV representation not just for Delhi, but desi hip-hop all-in-all, in a long time. Bigg Boss sees more than 120M viewers. That’s the potential audience that was exposed to desi hip-hop.

“Hai yeh man-slaughter barbarian style, kaidi kalai

Aur kalam ki nok se faili tabahi

Iss zakham ki hai ni dawayi

Pehle hi dedi safayi” (14)

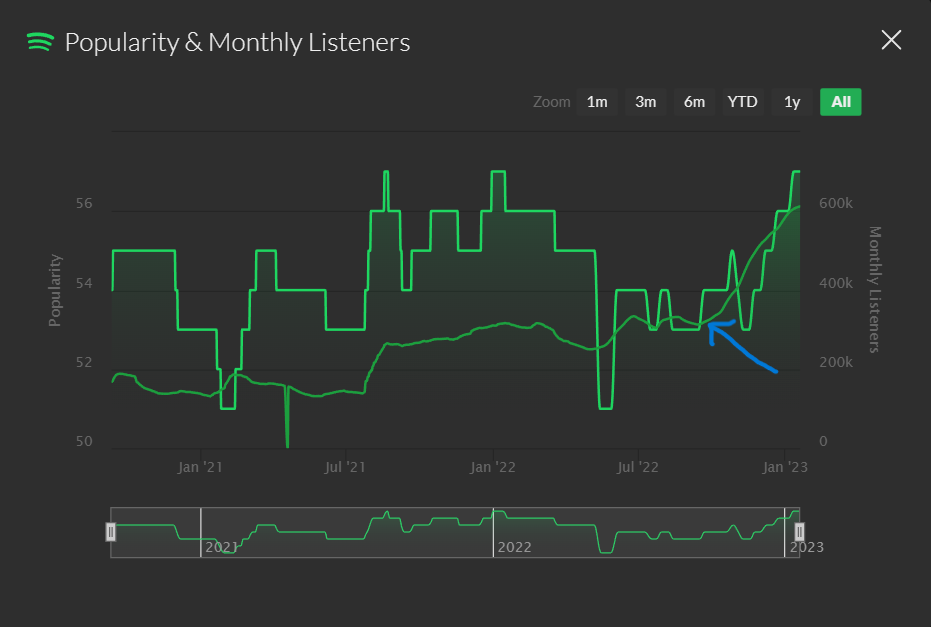

There are certainly some clear baton-holders in the Delhi scene currently, who are being heralded as changemakers. By virtue of their 2018 debut album Bayaan, Seedhe Maut (and Sez On The Beat) are one such frontrunner. Since 2018, the duo have racked up 600K monthly listeners on Spotify. If the blue arrow on the next graph is any indication, they have broken through the milestone beyond which growth would become unstoppable for them. The fact that they also released arguably their best album in Nayaab, in 2022, may have something to do with it.

In ~5 years, Seedhe Maut have racked up a fifth of the monthly listeners that Raftaar has, and a little more than one-tenth that of Ikka (who they have collaborated with). Both Raftaar and Ikka — who have been in hip-hop for around 15 years — came out of their own slumbers recently to remind everyone how good they can be. Their high numbers of listeners come from their deep work in Bollywood, as opposed to more independent catalogs. Ikka has only 2 albums of his own in his career, released in the last 3 years. So does KR$NA. These three rappers come from a more single hit-focused culture of making hip-hop about gloating.

The final track from his EP Hard Drive Vol 1, Raftaar’s JASHAN-E-HIPHOP is a scintillating display of the art that India and Pakistan can make together. Featuring Pakistani spitfire Faris Shafi, with a beat by Pakistan’s top producer Umair, JASHAN-E-HIP-HOP is the musical equivalent of two Mortal Kombat special moves fused together with a beat switch. It is a celebration, a jashan of the best hip-hop talent of the Indian subcontinent:

“Pade maar, sarhad paar baje Kalamkaar (Raftaar’s label)

Taape bina taar kare border paar

Gunehgar bar deti jaane maar

Baap ke udhaar pe na chale car” (15)

Delhi hip-hop has moved from the culture of making just flex and party singles, to full-blooded albums that deserve attention front-to-back. Bigger artists tend to have entire album rollouts — with the intention of introducing their fans to the web3 world, Seedhe Maut gave out free Nayaab NFTs on first-come-first-serve. The NFT holder got exclusive access to the behind-the-scenes for the album.

But little screams impact more than when you look at how one’s music has changed someone’s life. In November of last year, alcohol brand Simba sponsored a 2-day hip-hop fest called Uproar, which had many of these acts. Before Ikka came on stage, a fan was making his way into the stands with a large frame. The frame was a customized photo collage of Ikka bhai. Mid-performance, Ikka calls that fan on stage — who seemed to hail from the same area as the rapper. The fan was visibly very emotional, and hugged Ikka — who said that he would hang the frame in his own studio.

You see glimpses of similar impact in the YouTube comments section of these songs. Delhi’s rappers, and desi acts in general, have been able to tap into my generation’s frustrations about family, education, direction in life, money. They will be waxing lyrical on the internet about why they felt so much about a composition.

Home Base

“Dekhta sapne saare aukat ke bahar,

Ferdinand Magellan, lunga duniya ki naap” (16)

I’ve been in Delhi-NCR for 3.5 years. While in school, I had harbored ambitions to study in a top college in DU. College, job, love, situationship, relationship, good chole bhature, tandoori momos, a very weird police encounter (that ended harmlessly), protest, and a hit piece on Medium — all firsts that the city has given me.

I always have a song playing in my head. Life can often get boring, so I spice it up with some background score. Hip-hop has always been that score. It has been my source of optimism, because out of the 73 hours of music on my all-encompassing hip-hop playlist, I must be able to find at least 5 minutes’ worth of anger to get over a shitty Delhi landlord who will refuse to pay for the house’s main fuse blowing out.

I see those memories where the city gave me brain (or lung) damage, and now they’re painted with the lyrics from these songs. Yes, the motor for water supply stopped functioning. Did I meet a snooty kid in college who went to an elite Delhi school? Do I feel like it’s going to be a very lazy morning with an unhealthy breakfast? I have songs as answers to each of these questions.

Delhi hip-hop contextualized my memories in the city with respect to why the city operates the way it does. Why, despite its holes, it continues to have a charm in its natives’ minds. Or how I can survive the city — the music does both recommend healthy and toxic coping mechanisms.

I’ve neither laughed nor cried more anywhere else than I have in Delhi. I still remember the first time I rented a 3BHK flat near university — I was hit with my first anxiety attack because negotiating with the broker took so much out of me. Or when Gurgaon’s corporate-induced loneliness hit me like a brick, that I nearly stopped believing solitude was real. In such times, the F-bomb feels like an Uno +4 card that I can use anytime, anywhere, without consequence.

Of course, unless the other person has a +4 too. Much like this video.

The highs are high. When it’s me and the people I love, chilling at Deer Park, petting the cutest dogs doing ramp-walks on the dirt. Or walking across Janpath Road to get coffee from DePaul’s. Or having a picnic at Lodhi Garden against the gleaming sun. Or an extremely thrifty smackdown brunch at Majnu Ka Tila. Or dancing to AP Dhillon with strangers in one of Gurgaon’s BYOB machans.

Why I wrote entire treatises around friendship and love is because the Delhi experience is as good as toilet paper without them. Delhi hip-hop is most informed by those qualities. Seedhe Maut came together because Siddhant Sharma and Abhijay Negi met randomly at a SpitDope cypher. Rawal and Bharg met very similarly. J Block was much more haphazard — 13 people, all of whom didn’t know each other. Gair Kanooni is 4 people from different walks of life. School buddies Karun and Udbhav reconnected after a long time, and made some of the best music the city has heard.

In fact, Karun’s Heeriye, which also features Udbhav, Toorjo Dey and Barf (with the music video shot by Tarun), reminds me exclusively of what Delhi sunshine feels like. Karun loves poetry, and much of his music is centered around past romances. Probably why, when we spoke, he said that Honey Singh certified him a lover-boy:

“Kal aane wala, kyun mujhse puche

Mai tera kya banu

Dur na jaawe accha soniye

Hath mera padhle, mere heeriye, heeriye” (17)

Experiencing these joyous memories, with my favorite people, in the city that has become a part of me, feels emotionally overwhelming. When I return back home via the Yellow Line metro, I struggle to put into words what I feel. I wish Mirza Ghalib’s ghost would possess me so that I could write poems about how good my day was.

But on the metro back home, I want to hit replay on the memory. Be it cultural, culinary, lethargic, picnicky, I want to immerse myself in what I feel. That such a memory I could only experience in the capital, and I’m okay experiencing Stockholm Syndrome for it. The packed metro cabins feel lively and great. For once, I’ve beaten the loneliness so characteristic of living here.

I just play the music and take it all in :)

My favorite thing to write — the special thanks section. So here goes:

Waris, Saqlen, Faizan, Kabeer, Lonekat, Adam Bo, Akx, Circle Tone, dr chaand, Battery, Agaahi Raahi, VIP, ishan — J Block for being the loveliest hosts. Their next tape, Love Marriage Haldi Bangers, will be out very soon. I saw Lil Kabeer record a verse — I’m not sure if it was for this album, but it was fire. Apparently, the album has yet another landlord diss? The struggle never ends.

Saar Punch. I’ve had the pleasure of watching Saar perform Oopar Neeche live, and I am pleased to tell you that every son on it was meant to be listened to in open air. I hope he sells out shows soon. He intends to have a fruitful 2023, and is already off to a great start — Oopar Neeche just crossed 500K Spotify streams.

Tarun Kukreja, who’s been incredibly helpful. He wants to release more music this year (listen to his first release of 2023, Mujhmein), and — being a professional videographer — explore the music video side of things. He usually takes clients with love marriages and haldi bangers. Or bangers in general — he shot a Bohemia concert in Toronto.

Besides them, the rest of the artists who made RTHB possible: a) Bharg Kale — who’s all over both RTHB playlists for very good reason; I had the fortune of watching him and Saar perform Maykhana live; his new single Darta Hu Mai is out, b) Karun — who is enjoying an insane creative peak; his single Chaand is live, c) Viraj Gulati / idek — who will soon be releasing as part of Smitt & Wessn; I listen to their bop Big Boy to feel tall against Gurgaon’s buildings.

Gabriel Dattatreyan for being extremely helpful with the history, beginnings, and sociology of Delhi hip-hop. I envy those at NYU who study under him.

Ritika Varshney and Taran Kaur for being such sports to allow me to interview them. I learnt tons about desi hip-hop AND Delhi from talking to them. And I have tons of conversation material with them in my working document that couldn’t translate here. What if I also open my own podcast? Too much?

Sumit Roy, for giving me his time. A good amount of effort went into framing this piece, and his answers to my questions, while not explicitly here, have significantly helped bring focus to it. I’ve had the wonderful pleasure of catching one of his art exhibits, they’re a goldmine to the hip-hop fan in me. Check out his Instagram. He also has some rap of his own, here.

A repeat for all the other people who helped with the entirety of RTHB: Rijul Seth, Ishartek Pabla, Meher Sachdeva, Dhruv Trehan, Aditi Singh, Tanya Singh, Abhiroop Dey, Nicaia D'Souza, Jayant Bakshi, Manik Dua, Chhavi Bahmba, Shruti Gupta, Kushan Patel, Jayesha Koushik, Molina Singh, Sunaina Bose. It’ll never be enough to thank them.

Opium of the Masses / Paridhi Puri for translation. The Medium piece I mentioned earlier was co-written with her — she’s a better writer than I am. This newsletter would probably not have existed if we hadn’t written that piece. And Sharika Parmar for some very crisp Kashmiri-to-English translation on the lyrics to Elaan!

Lastly, thank you Alamy Stock Images for the beautiful minimalist map of the city.

Until next time — which is pretty much next month :)