Hello, good morning, namaste!

I have achieved what I always wanted to: one piece on Succession under my belt. To quote Kendall Roy, this is the day we make it happen. It’s not just a dissection of the show, but rather what it says about something real world. That being said: this piece has A FEW SPOILERS, so please exercise caution. Unless you do not care about spoilers affecting your watching experience and all that, in which case, please feel free to read this.

My job as a music selector for my pieces has never been easier than this time. I just entered “Succession” on Spotify’s search bar, checked out the playlist, and chose an appropriate banger that plays in the show. Honestly, the non-background score tracks that feature in the show are pretty damn fire. And they’re always commenting on the show, always.

Happy reading, and happy Sunday (or Saturday, if you’re on the other side of the world)!

It’s been a few months since the final season of Succession ended, and end it did with a — to quote Tom Wambsgans — “bang! Shanghai-ed into an open borders free fuck trade deal”. I’d say it was a great trade: we got to see a bunch of yuppie siblings quarrel over their father’s empire in hilariously disconcerting fashion. Sometimes, it gave us heart attacks. Sometimes, it gave us more laughs that we could bear. Sometimes, it teared us up to no end.

I’ve tweeted non-stop about how much I love the show since when I saw the first 2 seasons in the first pandemic wave. The brilliant acting, the ingenious curses, the anxiety and thrill in some standout episodes, the music. But for the purposes of this piece: there is so much the show gets right about the media/entertainment business. 2023 has been an eventful year on that front, and rewatching parts of the show in light of that fact feels like a rewind of real life.

One of my favorite pieces I read this year was Evan Armstrong’s (of Napkin Math) treatise on his love for media businesses — a sentiment I share. At the same time, he didn’t shy away from calling it a moment akin to a funeral for the industry. He lists 7 very compelling reasons why media business is so rotten, that you wonder whether this is a problem inherent to its economics. He has a wonderful summary for his piece:

“The TL;DR is this: Consumers don’t want to pay you, Facebook is better at advertising, and unique distribution is necessary for long-term survival but almost impossible to get.”

And it was just really good timing that Succession ended around the time this piece came out. The show ends with a conclusion that was seemingly inevitable, and I don’t mean in terms of what happened to the siblings. The finale marked the replacement of old money with new money, a process of the creative destruction of a (fictional) legacy company happening right before our eyes.

And it got me thinking: Succession really knew how messy media business can get. The industry is not just a backdrop for what it's trying to say, but a definitive part of how the plot advances. It dissects media companies of different sizes and dynamics to craft an incredible story. This piece is an exploration of how the show does that.

Hear, Here

Essentially, Succession represents media business at 3 major levels. Obviously, the first (and biggest) one I’m going to cover is Waystar Royco.

It’s no secret that Waystar’s biggest inspiration seems to be Fox Corporation and the Roys after the Murdoch family. Now with Rupert Murdoch ceding the Fox throne to his eldest son, the Kendall Roy fan club seems to have reason to rejoice (please don’t).

The FOX money labyrinth is interesting. They make money in two ways:

affiliate fees: subscriptions and fees paid by other television stations to market content owned by Fox

advertising.

It’s primary profit driver happens to be what it calls “Cable Network Programming” — essentially their news and sports content disseminated to the public through television stations not associated with FOX itself. However, it is not their primary revenue driver — which happens to be their own television network: producing, acquiring, marketing and distributing their own content. It just costs them a lot to acquire rights to sports content, which is why FOX Television’s own profits pale in comparison to its cable programming. Within this, the split of revenue types is different. While affiliate fees rule in cable programming, it’s advertising that drives much of Fox’s own network.

Throughout Succession, we’re told that ATN is the center of the circle. News is how they make much of their money. If this website is anything to go by, ATN seems to be the most popular news channel in the US. Affiliate fees must be skyrocketing for them. And advertising — a tool they know well enough to use to grotesquely manipulate and maneuver American democracy — must be incredible business especially in election years. They may also have their own content, produced or acquired, that they license to other networks.

An interesting deviation from Fox is the fact that Waystar does not seem to do sports at all. In 2021, the NFL signed 11-year contracts with CBS, NBC, Fox, ESPN and Amazon for a collective value of $110B. Sports is absolutely insane business. Assuming the contract values are split evenly, Fox will need to make at least $2B through sports viewing alone to break even. In the Indian context, the war for IPL rights says enough. Mukesh Ambani paid a whopping $2.7B for the exclusive streaming rights to the league.

Anyway, what could be the reasons that Waystar is declining? The reasons aren’t explicitly clear in the show and whatever we assume is by proxy of their position in the NYSE. Except for one: their tardiness in adopting digital. It is the primary basis of their potential acquisition. Seeing as how traditional newspapers, not just in the US but also in India, have been running out of fashion, being late to the party that was the internet could mean disaster. It is also cheaper to run ads on the internet that on print.

Here are other possible reasons I fathom might have caused Waystar operational issues:

Movies are high-risk business. Profits aren’t the easiest when worldwide marketing takes up so much of it. If we know anything about Waystar Studios, it’s that Roman Roy was once heading it. It was a stint that everyone alludes to as an example of Rome’s narcissism destroying his name. We really don’t get a sense of Waystar having any well-known franchises under its belt, but we are told that Rome absolutely tanked a couple of movies as a producer.

Waystar has theme parks, that Tom was once the head of. Disney’s (and Marvel’s) model is to make movies every year that bring people to spend more on theme parks, their most profitable division. Last month, it doubled its investment to $60B in the same. But if you don’t have a movie business that can’t advertise well enough for your theme parks, you’re likely bound to see a decline. It also costs a lot to run theme parks, which are naturally capital-intensive.

Was Waystar late to adapting to digital advertising? That’s an attitude that could result from a belief that the paper, the tabloid, and cable TV will stand the test of time. I can truly imagine Logan scoffing at the World Wide Web, much like many people did when it was first launched. Especially since he’s always wielded so much power (not just economic) through the paper and ATN News. “The internet? Sounds like a fucking genie pissing its own pants.”

I also believe that Waystar doesn’t benefit from Logan Roy being the alpha wolf for so long. Sure, he’s headstrong and all that, but to paraphrase what Kendall once said, this is a man who’s been in contention for so long just because he fucked multiple US heads of state. Even if he didn’t literally do that, it’s evidence enough that where Logan makes up for being superb at negotiating and arm-twisting, he lacks in foresight. I mean, look at all the yes men he surrounds himself with. And he’s only realized this too late.

Aside from being clubbed under “entertainment”, rollercoasters and cable TV are not necessarily compatible. Both businesses require different types of operational expertise. When Bob Iger first stepped down at Disney, he handed over the reins to Bob Chapek, who had led Disney’s theme parks business. One of the theses of this piece by CNBC is that Chapek understood theme parks better than anyone, but not, say, the innards of ESPN, ABC, or Pixar. That, alongside some other incredible mishaps, led to Chapek being replaced by the very man that gave him the reins to begin with.

It’s not like ATN’s rival, Pierce, seems to be any better. Their pride in being a news organization significantly more liberal than ATN only extends till when they’re making money. In season 2, we can see Nan Pierce being quite willing to listen to Logan’s offer — and accepting one on paper after the first round of negotiations at the Pierce estate. Nan Pierce, the matriarch of the family, is modeled much after Katherine Graham, a past owner of the Washington Post. Pierce News feels a lot more akin to CNN that way. Yet, owing to the political climate in the country, Pierce finds itself continually struggling financially throughout the show, even fielding an offer from the Roy siblings.

Someone close to me once told me a story about a regional publication well-known in its area, whose founder was planning his post-retirement succession to one of his children. The same founder also said to a close circle that he knew if he did that instead of giving it to someone smarter and more capable, the publication would be run down to the ground. While also admitting that he was too attached to not give it to his eldest child. I wonder if that’s what Logan often felt like.

In season 4, Lukas Matsson pitches buying ATN alongwith the rest of Waystar, hopefully moving it away from its conservative leanings. “IKEA’d to fuck”, “Bloomberg grey”-ed, offending no one, being “neutral”. It’s not that he truly understands the reasons why ATN is this popular. Until, of course, the candidate that ATN has no trouble voicing support for, Republican Jeryd Mencken, wins. At that point, Matsson is more than happy to set up a lobby with the office of the new POTUS.

Which really reminded me of a quote that Stewy once said for himself that also applies to Matsson: he was really just “spiritually and ethically and emotionally and morally behind whoever wins”.

(Mid)as Touch

The second kind of media organization that Succession expertly dissects is the kind that Vaulter is modeled after. Hot growth-stage startup propelled by venture capital funding; Vaulter was founded by Lawrence Yee. Waystar seems to have become a major stakeholder in Vaulter because of the deal Kendall struck in season 1.

Vaulter’s inspiration seems to come from Gawker, VICE, BuzzFeed, Jezebel, and the like. Maybe throw in a little TMZ into the mix. These companies are propped up by advertising money and content licensing revenue. The biggest challenge that these companies face, on the revenue front, is why any brand would choose to buy ads through them instead of AdSense or Meta. The valuation for companies like these is primarily decided by their growth. And the profit comes later.

I kid you not that the following screenshot is an actual headline from VICE. And you may do well to read the piece, just to see the headlines that Succession came up with. They’re hilarious, and so close to what Vaulter’s real-life counterparts come up with. “Meet the World’s Richest People Trafficker (He’s a Surprisingly Nice Guy)”.

In 2023, you’d probably lose fingers if you tried to count the publications that cut costs with layoffs. VICE was the biggest victim — they scaled back their audio team, their long-form video team, and stopped their flagship program “Vice News Tonight”. The company filed for bankruptcy, primarily with the intention to sell to a willing buyer. And no, it wasn’t without controversy at all — VICE executives that got to stay got paid million-dollar retention bonuses while much of their laid-off staff were yet to receive their severance checks.

VICE was valued at $5.7B in 2017. In the lead-up to that valuation, they were cut checks by Disney and Fox. They had a lot going on: film studio, ad agency, record label, London bar, an absolutely insane YouTube channel, basically things that they expected to make them money. Co-founder Shane Smith once said of his darling media group, “We are a modern-day Bonnie and Clyde and we are going to take all your money”. And he was extremely confident that VICE would be worth $50B by the end of the 2010s. Only to be valued at a mere $350M — a 16x drawdown — this year on filing for bankruptcy.

BuzzFeed stopped its famous News vertical earlier this year. I’d say that the bigger red flag was when it went public in 2021 through a SPAC deal. Many employees who were lured in with ESOPs (as a lieu for a lower salary) seemed to not be able to sell their shares on the day of the SPAC. There was also a walkout by News employees as the day of the SPAC deal got closer, fighting for better pay and working conditions. And on D-Day, BuzzFeed’s price tanked hard. It was a litmus for other similar companies, and it failed. We also are significantly smarter about why SPAC deals are very likely scams.

Vaulter was modeled precisely at this juncture, except that it was not independent anymore, owing to Waystar taking over control. The company is failing and Logan is looking to shape it up in whatever way. Roman finds out that Vaulter is unionizing, and Kendall tries to tell Lawrence to convince his employees otherwise, and “have some faith”. It ends horribly: Kendall goes the next day to fire everybody in Vaulter, White Waystar keeps just the intellectual property and name. And when Lawrence angrily asks why, Kendall infamously says this:

There is an inherent conflict in the perception of what digital media is and what the writers expect it should be. VICE was known for being edgy: “punk-rock” was the word most associated with it. I suppose the Bonnie & Clyde quote was some indication of that adjective. But to quote an ex-brand executive from the company:

“How do you scale the essence of a punk-rock magazine into a multi-billion dollar media company? There is no real answer. At some point, what got you there isn’t what you are.”

It is probably why after a while, you really only saw one kind of kitschy content from the likes of VICE and BuzzFeed. The quizzes, the wild articles about sex, the extremely click-baity titles, the lack of real news. If you were a writer, you’d hope to write about things you found interesting, meaningful. You’d want clicks but not at the expense of quality. BuzzFeed News reporter named Ema O’Connor once put it succintly:

“If they want digital media to be modeled on BuzzFeed then they have to do better. The traffic discipline — all of these things are the horror show version of what people think that digital media is and so we need to convince them ... that is just not acceptable.”

At some point, you wonder if the only way media firms can survive is if they have an extremely loaded backer with no direct ties to the industry, who probably just wants to own a huge mouthpiece. Say, Washington Post with Jeff Bezos.

We see Lawrence at the beginning of the show, in the first episode, where he’s in a boardroom with Kendall trying to coax him. He tells Lawrence that he will stuff so much money in his mouth, he will “shit gold figurines”. Lawrence rebuffed him, and said that he will bring Waystar down. That he “will not let Neanderthals in to r*pe my company.” Which sounds like a very overconfident man with no real way to make money. Like Shane Smith, who really thought he could sell hard and get away with it.

But El Dorado doesn’t exist. And in a cruel instance of foreshadowing, the Neanderthals won.

Reverse Viking

At last, we have the big daddy, GoJo. Founded by Norwegian Lukas Matsson. Somewhat of a merge between Elon Musk and Spotify’s Daniel Ek (at least by regional identity and industry, if not personality). A crossover between Netflix and DraftKings, an upstart but digitally savvy, and growing like a monster. Clearly, it understands that there is lots of money to be made in sports and betting, so it does that alongside. It doesn’t do news, it doesn’t have the biggest content catalog, but it’s a storm.

Or at least it was made to seem like one.

Before some market capitalization voodoo magic that flipped the equation, Waystar was primed to buy GoJo. Why not? Post the inception of the streaming model, legacy media players like Comcast, Disney, Warner Bros, all cashed in. They announced that they won’t be renewing licenses for their IP to Netflix, in favour of launching all of it on their own newly-built app. When Disney+ launched, its stock went from $100 to $150. Waystar wanted a piece of this promised land.

User growth, not profit, has been the primary driver of the valuation of streaming models. In the beginning, it seemed revolutionary: making lots of content accessible at a monthly price seemed like a great bargain. Except for when streaming decided to splurge on a lot of content: like Prime Video spending $250M for the rights to a Lord of the Rings TV show. Art was reduced to content driven by algorithms. How much could you consume / binge in one sitting?

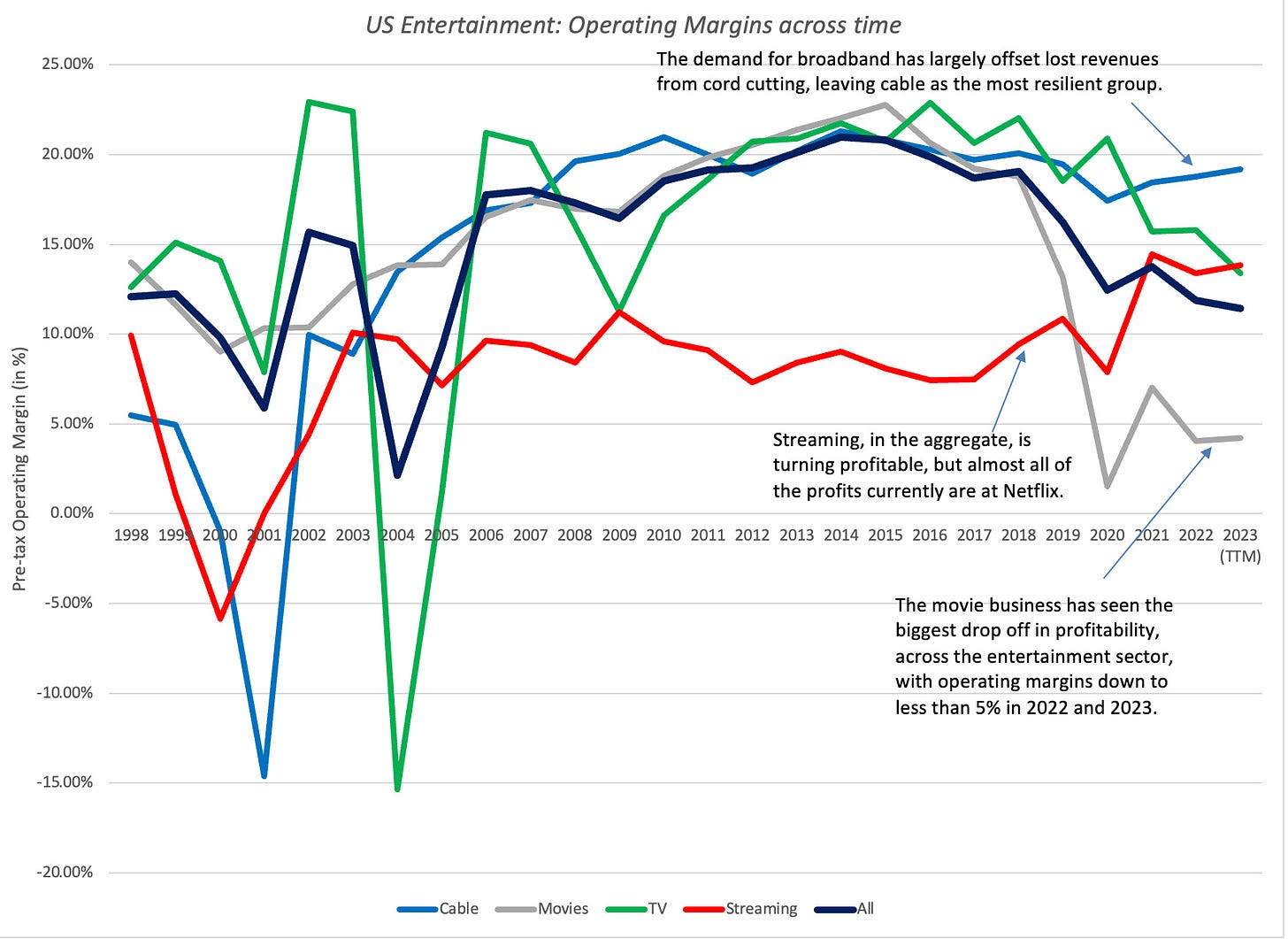

Aswath Damodaran did a killer breakdown of all the ways in which streaming upended the movie and broadcasting business. And he shows two wild charts that bring much into question about the sustainability of the subscriber video-on demand model. The story is this: SVOD’s operating margins are much lower than that of cable, movies and TV. But the industry’s market cap is rapidly increasing. I’m not sure if that screams “sustainable” to me.

Most notorious has been Netflix’s extreme hesitation to show numbers, which the show also spins into a point of contention in season 4. Kendall and Roman draw in Matsson’s head of comms, Ebba, to deal in trade secrets about GoJo. Ebba is pretty disgruntled with Matsson because he turned out to be unhinged and creepy. She reveals some number-fudging (Matsson calls it a metric error) in the India business on his part that would not have made sense even “if there were two Indias”. Of course, Shiv confronts Matsson about this, seeing as how she was backing him to get herself to ruling Waystar. When she asks him why he doesn’t address the issue already, his response is one that borrows straight from Elon Musk’s mouthpiece:

The fact that he doesn't want more people betting against him in the market in one of the few instances where his insecurity really comes through. And he says that this number-fudging will eventually get lost in the shuffle when he buys Waystar. Matsson is unbelievably pushy about buying out ATN throughout the season likely for this reason. Even when Ken and Roman tried to self-sabotage the deal when they realized they didn't want to give their baby up, Matsson offered a price so incredulous that the board and shareholders would have no choice but to accept. At some point, you have to wonder if Matsson was self-aware that he was running something resembling a Ponzi scheme. I also wonder if there was a large short already running against GoJo.

Succession ended in May, which is also around the time the Writers’ Guild of America started their strike. Among their demands from the AMPTP was that of revealing audience data for how many people watched a show they wrote, so that they could have more bargaining power for future deals. More than fair: it’s what happened with cable TV, that also granted them residuals based on Nielsen ratings. To quote the CEO of a talent agency, “If one group is staring at a set of figures and they’re negotiating with another group who doesn’t have any numbers, it makes it a very one-sided conversation.” The WGA recently fully ratified their new contract details and concluded their picket, but SAG-AFTRA is still on the line for their own.

You also have to wonder why the writers chose to use India in that piece of dialogue. Netflix India has been trying to crack profitability for an endless amount of time, launching extremely cheap plans that won’t be found in most other countries. Disney is planning to either exit or significantly dilute its stake in its India business, and we’ve already started to see its effects: HBO and IPL are both properties of JioCinema now. Foreign players have been desperately trying to sell their services for as cheap as they can, only to realize that we either can’t or won’t buy.

(Which is also a harkening back to a piece where I wrote something similar from a vastly different angle earlier this year.)

While I was writing this, Bandcamp laid off much of their staff. For many of us tuned into music and musicians being able to make a career off of music, it was heartbreaking to see an operation that paid out so well to artists for their music cut back on the people that made it. The company has gone through two different acquisitions: first sold to Epic Games last year (in a cost-cutting process of their own), who sold it to Songtradr this year. It raises serious questions about how Bandcamp is being managed.

The video streaming question certainly also applies to music streaming. It’s great that music has become more accessible to people through Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube. But per stream payouts to artists are not great, at least for Spotify — despite paying 70% of every dollar they receive as revenue to the music industry. The good part is that music streaming is and has been a growing business for some time. But, if India is any indication, Spotify is a little desperate with its pricing, too.

Epic Games itself went through a layoff late-September: reports suggest that it’s majorly Fortnite (itself declining in player-base) keeping them afloat. Their Games Store expects to be gross-profitable only by 2027. Their revenue and profit projections for the entire company have gone down.

It’s been some year for the arts, and the business of it.

We saw a finale season for the ages, crafted by incredible artists at the top of their game. But on looking back, Succession has probably always been as much a commentary about family and capitalism as it has been about the artists that made the show. It was never about the writing feeling prescient. These are issues that are only reaching their head now, where we feel like a decision of some sort has to be made on the future of the industry and the people it employs. And maybe it was just eerily perfect timing that a show that always knew what it was talking about got way too close to real-life than it expected.

And this is counting the players that have historically done well anyway: be it A24 being a beacon of profitably making amazing movies, or Valve being a behemoth (with a ridiculously good per-employee revenue), or The New York Times making money (though often with suspect journalism and questionable headlines). These feel like exceptions in an industry where things feel fundamentally broken.

This applies to music, movies, news and print, and probably even gaming. We’re exploring new media formats all the time, expecting that, hey, maybe podcasts could be the next big thing. Maybe VR kits, the metaverse. Maybe a Bandersnatch-like project could be the next wave of entertainment that everybody will line up for. Maybe enacting a real-life fun Squid Game (why) for YouTube could be cool.

All that Succession has to say is, “Let’s just take all of these assumptions we’ve made about the state of the industry and take them to what we feel is their most likely conclusion.” If we know anything about the show, it’s always been about the inevitability of things already set in motion.

Thanks to Paridhi Puri /

, Sunaina Bose, Shruti Gupta, Ritwik Tripathy, and for proofreading and edits (and giving instances of more Succession business lore that I had missed)!As usual, will be back next month! I still don’t know which piece I’m writing (one of two ideas), so I should get cracking on researching both :)