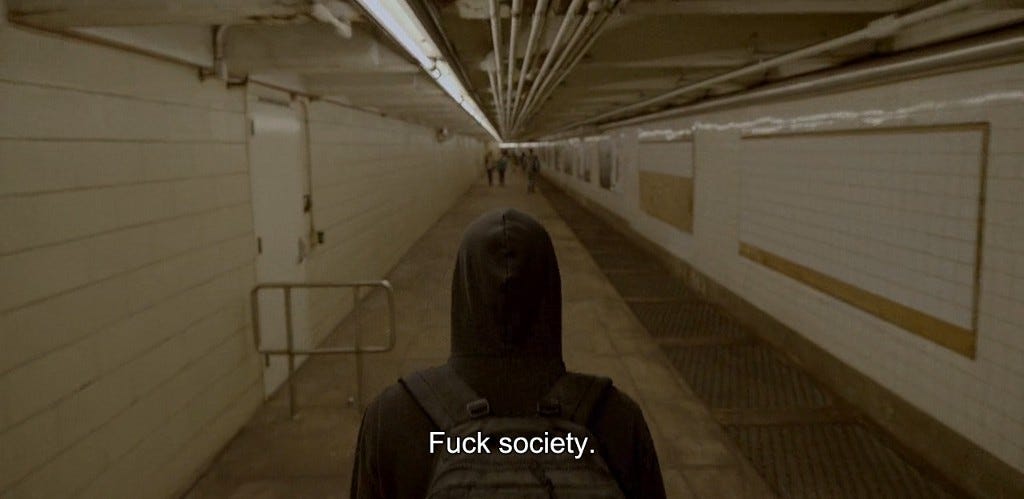

We (Don’t) Live In A Society: inside the toxicity of Delhi University’s society culture.

[co-authored with Paridhi Puri]

Delhi University is a dream destination for lakhs of Indian students every year. They’re promised quality education at prices far cheaper than its private counterparts. More than that, they envision a freedom they would never have experienced before. No one will force you to attend classes, and some may arguably say that much of the learning in the university happens outside class. An important factor contributing to this rosy picture is the university’s society culture. You are told that you can find your niche here, and you’ll make some of your closest friends. For the longest time, societies have been massive crowd pullers. The fear of missing out becomes too strong for a new student to handle.

However, what doesn’t seem to be acknowledged enough in the open is that in the past few years, society culture in DU has become incredibly toxic in a variety of ways. They’re not the paradise they pitch themselves to be. We aren’t simply talking about ego clashes stemming from conflicts of leadership and direction. We drill down the exclusionary nature of these societies right down to their inherent structure. And only then, we talk about how those ego clashes manifest themselves in the most soul-consuming forms.

Before we flesh this piece out, we’d like to acknowledge our own roles in this culture. We can’t absolve ourselves of this simply because we choose to write about this. The only purpose of this piece is to spark confrontational conversations about toxic society culture, and not reduce them to just being “open secrets” anymore.

The problem, arguably, begins with the society intake process — an exercise that early on shows you how skewed the power dynamics of societies are. Under the garb of interviews, group discussions or auditions, seniors create an extremely intimidating environment. This is a facade, perhaps — to show all candidates how ‘prestigious’ and tough-to-get-into the society they’re hoping to join is. Keep this in mind — freshers who join the university come from diverse backgrounds. A lot of them lack social capital, come from an underprivileged caste background, or towns where the same idea of extra curricular activities isn’t present. It’s exceedingly myopic to view everyone from the same purview of privilege. A lot of people are denied the chance to fully explore the milieu of extra curricular work, by these intimidation tactics. We’re not pointing fingers at any particular circuit, or college society. This is perhaps a fixture in most of them, and the glaring harm it does, moreover, as it’s passed from batch to batch, cannot be understated.

Here’s what we are saying — when a fresher enters your college and seeks to be a part of your society, don’t shut them out if they don’t meet your superfluous criteria. A lot of it concerns being able to speak proper English, or having enough experience and depth of thought about the society’s endeavours in the first place. Don’t make your freshers go through a gruelling series of interviews, that more often than not, becomes their first taste of what college has to offer. Break down your idea of merit. Try to make more inclusive plans of induction — and we promise it’ll be worth it, because societies should be more about learning than gatekeeping.

The society structure causes so much mental fatigue, and we’re sure all of us are familiar with this. A fundamental problem that arises is, ofcourse, the oh-god-I-need-PORs-and-certificates-for-my-Resume industrial complex, otherwise I’ll lag behind. Here’s the thing, of what I’ve learned from two years of college life — no certificate, or leadership position, or letter of appreciation is worth the mental and emotional exhaustion it’s causing you. In my first year, like the clueless fresher I (Paridhi) was, I signed up for five societies, and proceeded to sleepwalk through life because of how utterly miserable I was. Sure, a lot of the issues were personal, but I would be lying if the constant pressure to participate, appear in meetings, contribute to events and so on — didn’t take a toll on me. It’s very easy to post a status or even be genuine (I mean it) when you say, ‘reach out to me if you’re going through something, I’m here for you’. But, it’s very hard for people to realise how the very guise of being normal, that every hyper-competitive space in college demands from you causes anguish. TL;DR if you’re going through shit and your society either augments that, or is one of the sole reasons for that, leave it. You’ll be much, much better off (coming from experience) and will have the mindspace to engage in the same things you joined the society for, albeit more fruitfully and happily.

‘We’re a family’ — possibly the most overused trope in the cinematic universe of DU Societies, and I don’t mean it as a compliment. Of course, it’s natural that you meet people in college, who from the virtue of their personality, or the amount of time you regularly spend with them, become close to you. College is a time when a lot of us form meaningful and healthy bonds, that stay by our side when we are at our worst. If your society helped you found that, it’s great. But don’t forget — societies are hierarchies of privilege, with skewed power dynamics because of one’s social capital. We can’t erase this fact. It’s a projection, the best of your Instagram perhaps, but we can’t possibly ignore how many people become enablers of the same things they fight against in their personal (and political) lives. For students who tend to be introverted, or less sociable, this becomes a bigger problem. They’re welcomed with open arms into the society, only to feel more claustrophobic with time. Their seniors admit that this society is everything to them. They only come to college for the society. It’s their reason for waking up in the morning. They don’t go to class, and their juniors should follow their footsteps. That might still have been understandable if the learning curve they offered instead was huge. Usually, it isn’t. If you leave the club later, they stop caring about you. They ride you, and demand that you work on sponsorships and organization at the expense of your internship, or your classes, or your extra courses. All the people they care about are in the club, and that’s often by their own admission.

DU society culture has taken a form where it’s not a stretch to liken it to American college fraternities. Much like a fraternity, only certain people at senior levels decide how the society is run, under the pretense of taking inputs from everyone. The same seniors complicate interactions with their juniors. On paper, they will appear friendly and nice. The problem arises much later, when they start berating and infantilizing their juniors, despite having only a year’s, or two years’ worth of life experience more than juniors. That happens in terms of the society fest work involved, or even in general conversations. It can beat your self-worth down, and make you disbelieve your own potential. This is especially true of the attitudes of the men in the society towards the women. Stories of mansplaining abound in these societies. If the senior-junior dynamic tends to become non-platonic, the infantilization becomes even more toxic. The senior also tends to hold far more power in a society, which naturally causes some fear in the mind of a junior. The hazing rituals are too subtle.

Another hugely problematic aspect of most performing societies is the existence of circuit confession pages. These pages are breeding grounds for virile hatred for performers, rumors and speculations. The indulgence — even glorification of rampant misogyny, casteism and racism that goes on in these confessions is confounding. It’s notable how much of the vitriol is received by students of women colleges and queer folks. This is the manifestation of Brahmanical patriarchy. It is so loudly present in most society spaces, and goes unquestioned year after year.

While DU fest culture has gained notoriety in the past few years because of the ghastly harassment that goes unchecked in these events, few people have challenged the internal workings of societies during this period. Students are made to work everyday for unearthly hours, with no attention to their physical and mental health. Various members of performing societies have reported cases of mistreatment by seniors, who put so much pressure that it’s hard to not crack. There are so many harmful practices every circuit has adopted and encouraged over a period of time, maybe decades now. The cost of winning shouldn’t be someone’s health or passion for the activity.

It’s also an ugly open secret how societies have been condoning and participating in rotten things — misogynist traditions, casteist slurs, rites of passage and God forbid, abuse; under the garb of a one-big-happy-family. This enablement often takes ugly shapes, in the form of a lack of due process with respect to instances of sexual harassment. Next to none of these societies have any proper method of dealing with these problems. They will usually follow a centrist, appease-all-parties solution, as opposed to one that focuses on justice to the victim. This issue worsens when the top post-holders of a society are cisgender heterosexual males.

It’s ironic that the movie adaptation The White Tiger was released only recently, because it’s evident that students are trapped in some form of a rooster coop. The protagonist’s analogy goes as such: chickens don’t see a way out of the coop, and see no choice but to appear like they’re enjoying themselves. Yes, you can imagine who the butcher symbolises. All of us have been in societies that function like the average chicken coop. We form a love-hate relationship with the society: By day, we rant against it, and the people who run it. By night, however, we find reasons to stay, and those reasons would be somewhat valid.

This creates a blur between the club and the activity it represents. For example, if it were a society about cooking, I start to see little difference between both. My hatred for the society starts extending to the activity. As unfortunate as that sounds, it’s often true. The people who run these societies don’t make it conducive for new entrants to truly enjoy the activity. They don’t take enough of a proactive role to do so, either. Sometimes, it’s because they will have other priorities, and that may be fair. However, there have been instances where seniors go out of their way to make someone feel uncomfortable. When people quit because of this, active members of the society, who were always privileged enough to feel comfortable in it, ask “why”, without the slightest idea of the same.

Freshers are often screened away from the behind-the-scenes. But this culture is a cycle that gets propagated very subtly. At a point of time, seniors had also merely started out. They had to have learned this behavior from someone or somewhere. The justification for this becomes “we had to go through this, so you have to as well”, not “we had to go through this so you don’t have to”.

More importantly, the world outside college is hellishly competitive. Information asymmetry causes issues in terms of knowing what stands out to employers. Societies get their power from this asymmetry. Freshers start believing that widely advertising on LinkedIn that they’re merely members, or even seniors in a society is a signal, while the truth couldn’t be further from that. We’ve seen this happen every year, without any actual return on updating that headline. This is also significantly different from what students who do not study in DU do: their societies and activities are only a part of their profiles or resumes, and not the headline itself. It’s not necessarily ideal to show that you’re a jack of all trades, because no employer or academician will believe that simply because you’re a part of 10 societies.

We have personal proof of this trend as well. In an interactive session, one of the authors of this piece was asked what societies one must join to make a killer resume. That question only arises because all societies aggressively market themselves to freshers right when they enter college as beacons of learning and personality development. There’s natural confusion in the minds of freshers. Some of them drop their beloved hobbies to join societies that will supposedly enhance their profiles. The obvious answer to that question should be “keep doing what you love, and people will notice regardless”. It’s an open secret thrown around that certain people join societies just because it looks good on a resume. To be honest, it never works that way. Moreover, it’s very obvious that society work only showcases your ability to hold your own amongst a small group. Your competitive ability will also be judged by your work experience, grades, academic projects, and actual, tenable skills.

Not many will admit to societies proving to be the knowledge bases they painted themselves as for recruitment. Most likely, they’ll say that they learned some important skills on their own. It begs the question, “What is the value proposition of clubs in Delhi University today?” There’s a possibility that if you ask enough post-holders in societies, they’ll express their disgruntlement in that regard. Even if the society has unique value to what it does, politics provide enough of a barrier to you truly enjoying it.

We don’t want to end this piece on a pessimistic note, or on a note that effectively calls for doing away with college societies. To a large extent, they provide a haven for students to thrive outside the classroom. That is crucial to a vibrant college environment. As once-freshers in the past, we understand that for some of you, reading this might be a bit much to grasp. This piece feels incomplete without pitching any solutions to make societies more wholesome and inclusive.

The open society structure is a possible solution. If implemented, it may echo the progressive politics that is only preached in society circles. It basically allows students to sign up for a society without the added formalities of multiple auditions, interviews as such. Membership of the society is based on someone’s interest in the activity, and not their merit or previously gained experience due to privilege. Such practices, of course, differ across the spectrum, depending upon the activity the society indulges in. But we would be lying if variants of the same cannot be introduced by society circuits in their recruitment process, competitions, and even the core leadership team. An open society can also remove the need to provide certificates based on simply staying in it for a duration, unless someone has truly shown interest in the activity. While colleges may have their own Internal Complaints Committee, we feel it is important for societies to have redressal mechanisms for complaints. These committees within the society should consist of members who are not cis men, and preferably, those who do not occupy the highest level in the hierarchy of leadership. This is to facilitate accountability for all members in the society, and to ensure that all complaints are addressed swiftly. Appropriate action can be undertaken, one which may be the first step in a series of future measures. These are just some remedies we mention; we do think that with considerable deliberation, more adaptable yet convenient solutions can come forth.

This piece has been informed by stories both of us have heard directly and indirectly. We would be out of bounds narrating any of them explicitly. However, we also think that we’ve described a general attitude of distraught that many will identify with. We’ve tried to touch upon a wide range of issues here. If any of them touched a nerve, we implore you to introspect about the workings of your own society. We understand that reform takes time, a lot of effort, and going against the establishment. We believe that many stories have been suppressed by virtue of people quitting societies in disgust. It is entirely possible and scary that this piece doesn’t cover every problem, either. We hope that this article gathers enough attention among people in the university, and that it gets shared among people, in WhatsApp class groups, and society groups. We hope that this article sparks a much needed conversation, that will eventually give way to a thriving society environment that is beneficial for all.

[Edit: We’ve been getting a lot of lovely (and often heartbreaking) responses to this article, and we’re grateful for all of them. If you have anything to say to us on that front — experiences, bouquets, brickbats (constructive, not destructive criticism), we’re keeping our mail IDs open:

Pranav Manie: manie.pranav@gmail.com

Paridhi Puri: pari24puri@gmail.com

Toodles!]